By William Pearce

Perhaps the only thing faster than Frank Lockhart’s phenomenal rise on the early auto racing scene, was the tragic end of his career. Nicknamed “Boy Wonder” by the press, Lockhart only raced at the Indianapolis 500 twice. His first run was in 1926 when he took the place of an injured driver in a 183 cu in (3.0 L) Miller race car. During practice, he set a one-lap track record of 115.488 mph (185.86 km/h). During the race, he passed 14 cars on the fifth lap as he made his way to the front from starting 20th. He went on to win the race with over a two lap lead.

At Indianapolis in 1927, Lockhart qualified first, at 120.100 mph (193.28 km/h). At the time, it was the fastest lap ever recorded on the track. He led the first 81 laps of the race, a record that would stand for 64 years. After a pit stop, he regained the lead on lap 91, only to have a connecting rod break on lap 120 and take him out of the race. Of the 280 laps he ran at Indy, he led 205 (73.21%) of them. Lockhart is one of only three drivers to have led more than 45% of their laps at Indy, and he has the second highest percentage overall (Juan Pablo Montoya has the highest percentage of laps led at 83.50%, for 167 laps led of 200 run).

In May of 1927, Lockhart set a qualifying record of 147.729 mph (237.74 km/h) on the 1.5-mile (2.4 km) board track at Atlantic City, New Jersey in his 91 cu in (1.5 L) Miller race car. It wasn’t until 1960, 33 years later, that another driver turned a faster lap at an American speedway. In his short American Automobile Association (AAA) career, Lockhart started 61 races, won 27 of them and finished in the top three 37 times.

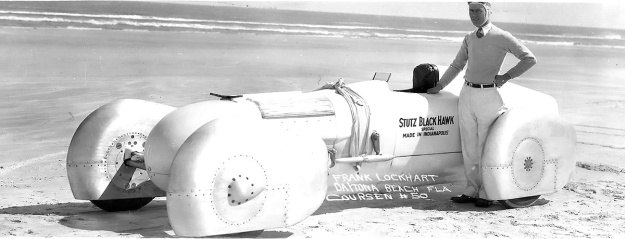

Lockhart sits in the Stutz Black Hawk LSR car during its unveiling at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

But Lockhart was more than just a race car driver; he was an innovator with the mind of an experimental engineer. Between the 1926 and 1927 season, Lockhart and his team, which included Zenas and John Weisel and Ernie Olsen, developed an intercooler for Lockhart’s supercharged 91 cu in (1.5 L) Miller engine. They had noticed that while the supercharger pressurized the air, it also heated it, making it less dense. If the air could be cooled, the denser air would allow the engine to create more power. Later in the year on 13 June 1927, Lockhart filed a patent for his intercooler, and U.S. patent no. 1,807,042 was issued on 26 May 1931.

On 11 April 1927, Lockhart took his standard Miller race car to the Muroc Dry Lake in California for an International Class F record attempt. This race car was powered by a supercharged Miller 91 cu in (1.5 L) engine equipped with Lockhart’s intercooler. Lockhart established a new class record, averaging 164.009 mph (263.947 km/h). At that speed, Lockhart became the fourth fastest driver ever, behind only Henry Segrave’s 203.793 mph (327.973 km/h) run in the Sunbeam 1000 HP Mystery (The Slug), Malcolm Campbell’s 174.883 mph (281.447) run in the Napier-Campbell Blue Bird, and J.G. Parry-Thomas’s 171.019 mph (275.229 km/h) run in Babs. All of the faster vehicles were purpose-built Land Speed Record (LSR) cars powered by large, powerful aircraft engines.

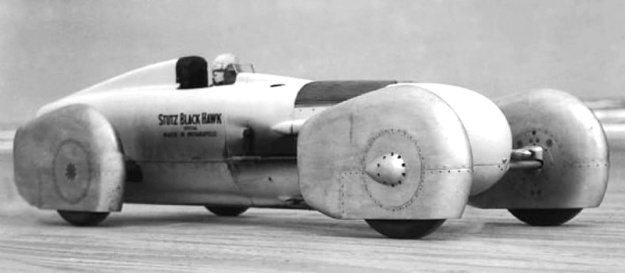

Lockhart ready for a run in the Black Hawk at Daytona Beach in February 1928, as spectators look on. The hole on the top of the car, in front of the cockpit, was the carburetor inlet for the right engine bank. There was another hole on the other side for the left engine bank.

By mid-1927, Lockhart had become focused on building a LSR car to break Segrave’s current world speed record of 203.793 mph (327.973 km/h). Lockhart partnered with Fred Moskovics, President of the Stutz Motor Car Company, to build the special LSR car. Lockhart and the Weisel brothers designed the LSR car. The Stutz Company funded about half of the project, so the LSR car would wear the Stutz name. Lockhart funded the rest of the project from his race winnings.

A team was assembled in Indianapolis to build the LSR car. What emerged on 12 February 1928 was the Stutz Black Hawk Special—a comparatively small streamlined car powered by a 180.4 cu in (2.96 L) Miller V-16 (more accurately a U-16) engine with intercooled twin superchargers. The intercooler was formed into the engine cover, allowing air flowing over the car’s body to cool the air/fuel mixture before it entered the engine. The car was made up of a central body, with each wheel housed in its own streamlined fairing. The Black Hawk was perhaps the first car to be designed with the aid of a wind tunnel. Scale models were tested in both the Curtiss and the Army Air Services wind tunnels. Reportedly, the car’s wind resistance was measured as .0061 lb/mph². The Black Hawk was 15 ft 9 in (4.80 m) long with a 112 in (2.84 m) wheelbase. The body was only 24 in (0.61 m) wide, and the car’s total width including the wheels was around 60 in (1.52 m).

Seen here are the two Miller straight-eight engines mounted on a common crankcase that made up the Black Hawk’s 16-cylinder engine. In this rear view, one can see the gears of the crankshafts are geared to the lower, central gear.

The engine was basically two 91 cu in (1.5 L) Miller inline-eight engines installed 30-degrees apart on a common crankcase. Each straight-eight engine’s crankshaft was geared to a central gear at the rear of the engine. The flywheel was attached to the central gear. To cool the engine, a tank in the font of the car held a radiator that was cooled with 80 lb (36 kg) of ice. The engine’s bore was 2.1875 in (55.56 mm), stroke was 3.0 in (76.2 mm), and weight was around 630 lb (286 kg). The engine produced more than 550 hp (410 kW) at 8,300 rpm and, utilizing the wind tunnel data, was predicted to propel the 2,800 lb (1,270 kg) Black Hawk LSR car to a maximum speed over 280 mph (450 km/h). The estimated cost of the LSR car was between $70,000 and $100,000 ($0.9 to $1.3 million in 2013 USD).

Lockhart joined Campbell and other racers at Daytona Beach, Florida in mid-February 1928 for speed record runs sanctioned by the AAA. On 19 February, Campbell set a new record at 206.956 mph (333.064 km/h) in the now more-streamlined Napier-Campbell Blue Bird. The next day, Lockhart made one run against the wind at 200.222 mph (322.226 km/h). This was slightly faster than Campbell’s against the wind run from the previous day. Unfortunately, clutch issues prevented Lockhart from making the return run.

An optimistic Lockhart in the cockpit of the Stutz Black Hawk on the beach at Daytona in February 1928. Bill Sturm is at the front of the car adding ice to the cooling tank, as Jean Marcenac approaches with more. Ray Keech is standing next to Lockhart. Note the finning on the engine cover that served as the intercooler.

With the sanctioned event coming to a close, Lockhart made another run on 22 February in bad weather conditions. During the run at over 200 mph (322 km/h), Lockhart encountered a rain-squall that reduced his visibility to nothing. He lost control of the car, and the Black Hawk spun into the sea, rolling over several times. Lockhart was pinned in the car as the waves crashed over his head. Spectators rushed to his aid, shielding him from the incoming waves and holding his head above the water while others attached ropes to the car. More spectators joined in and began dragging the car to the beach, until a tow truck arrived to pull it the rest of the way in. Lockhart had to be freed from the wreck with the aid of crowbars and blowtorches. He suffered three severed tendons in his left wrist, some bad bruising, and was in shock.

The Black Hawk was transported back to Indianapolis where it was quickly rebuilt and repaired. Lockhart, his car, and his team arrived back at Daytona Beach on 20 April 1928, only two months after his accident. Again, the speed record runs were sanctioned by the AAA, and other racers were present. Also making runs was Ray Keech in the White Triplex, a vehicle powered by three Liberty V-12 aircraft engines.

Spectators, press, and police rush to the aid of Frank Lockhart after his car has rolled into the surf. Lockhart could have drowned had it not been for O.D. Craig holding his head above water.

On 20 April 1928, Lockhart made a run and achieved 200.33 mph (322.40 km/h) on the return leg. The Black Hawk’s Miller engine was suffering carburation problems. Meanwhile, Keech made a series of runs, steadily improving in speed. On 22 April 1928, Keech got the Triplex up to an average of 207.55 mph (334.02 km/h), setting a new world record.

On 25 April 1928, Lockhart made a test run during which his rear right tire locked up under braking during the return. The carburation problems seemed to be resolved, and by 7:30 AM, Lockhart was making another run. The first leg was recorded at 203.50 mph (327.50 km/h), and everything went well. As the Black Hawk was prepared for the return run, Lockhart told his team that he was going to go for the record. Screaming down the beach at over 220 mph (355 km/h), about 700 ft (213 m) before the end of the course, the right rear tire blew, and the Black Hawk went out of control. The car skidded in the sand for about 400 feet (122 m), went sideways, and became airborne. The Black Hawk traveled another 503 ft (153 m), crashing down on the beach several times as it rolled. Lockhart was thrown 51 ft (15 m) from the vehicle. He was transported to a hospital where he was pronounced dead, Lockhart was only 25 years old.

Subsequent investigation revealed that the right rear tire had been damaged at some point during earlier runs. The tire had continued to deteriorate as the additional passes were made. The 16-cylinder engine was salvaged from the Black Hawk wreck. It was rebuilt and installed in the Sampson “16” Special, owned by Alden Sampson. Bob Swanson raced the car in the 1939 and 1940 Indy 500, finishing sixth in 1940. The car was also driven by Deacon Litz in 1941 and Sam Hanks in 1946. The Sampson “16” Special, with the 16-cylinder engine still installed, is currently on display at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Hall of Fame Museum in Indianapolis, Indiana.

There are two Lockhart Stutz Black Hawk replicas. One replica is owned and displayed by Turner Woodward in his historic Stutz Building in Indianapolis, Indiana. The second is a running (but not with a 16-cylinder engine) replica that is being finished by Jeb Scolman of Jebs Metal and Speed in Long Beach, California.

The following is a YouTube video (sorry for the music) of the ill-fated speed run uploaded by SportingHistory. The south-bound (ocean on the left) run is shown from the air first, and then the north-bound return crash. The crash is very violent.

This article is part of an ongoing series detailing Absolute Land Speed Record Cars.

Sources:

– Frank Lockhart: American Speed King by Morgan-Wu and O’ Keefe (2012)

– The Miller Dynasty by Mark Dees (1981/1994)

– http://gordonkirby.com/categories/columns/archive/lockhart_legend.html by Gordon Kirby

– http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Lockhart

– http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Indianapolis_500_lap_leaders

– http://blog.hemmings.com/index.php/2011/09/28/replica-of-the-ill-fated-stutz-black-hawk-special-to-debut-at-long-beach-motorama/

– http://www.autoweek.com/article/20061222/free/61206028

What is the correct wheelbase on the Lockhart Black Hawk special? My orthographic images (all 2300 of them) are filed under that datum. I am reached at my Facebook blog “looking back racing” if anyone wishes to follow the threads there.

Hello, and thank you for pointing out the incorrect metric conversion. The Black Hawk’s wheelbase was 112 in (2.84 m). The article has been updated with the correct conversion.

William Pearce

As a follow-up to this, here’s an article covering the recreation of the Stutz Black Hawk by Jim Lattin by help of Jeb Scolman: http://www.drivingline.com/2013/07/stutz-black-hawk-streamliner-recreation/.

Love Old Machine Press, thank you for all the historical digging!

Hello Kristin,

Thank you for the link and the kind words. That recreation is simply stunning.

Regards,

William Pearce

I was pleased when a search for the Stutz Blackhawk brought me here. My brother had a tiny plastic Black Hawk back in about 1955. Certainly one of the coolest cars of the 1920s — I didn’t know how sophisticated it was.

Any idea where any of the remains of Lockhart’s car are, these days?

As I mentioned in the article, the engine is in the Sampson “16” Special in the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Hall of Fame Museum. I do not know what happened to the body, but I doubt any of it exists. Probably the engine is the only thing from the Black Hawk that survives.

Interested in purchasing model (kit or finished) in 1/25, 1/18 or 1/43 scale, preferably resin, of LSR BLACK HAWK 1927/’28… (driver Frank Lockhart)