By William Pearce

Donovan (Don) Reese Berlin had worked as the Chief Engineer for the Curtiss-Wright Corporation. He had designed the company’s successful P-36 Hawk and P-40 Warhawk fighters. Berlin also designed a number of unsuccessful fighters. He left Curtiss-Wright in December 1941 in frustration because he felt the company was not sufficiently supporting his efforts to develop a new fighter. At the request of the US government, Berlin was quickly hired by General Motors (GM) in January 1942 as the Director of Aircraft Development at the Fisher Body Division (Fisher).

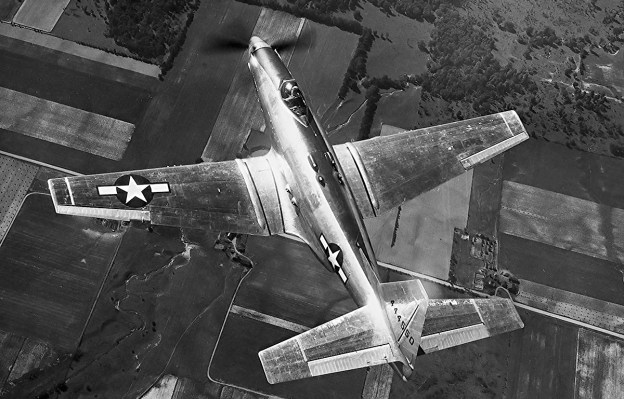

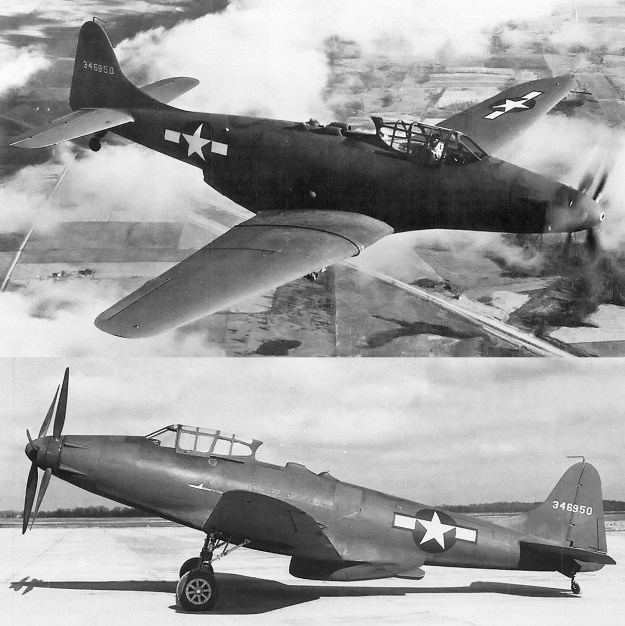

The Fisher P-75 Eagle was supposed to be quickly and inexpensively developed by utilizing many existing components. However, many resources were expended on the aircraft. The first XP-75 (43-46950) had a uniquely pointed rear canopy. It was also the only example that used a relatively unaltered Douglas A-24 empennage. Note the fixed tailwheel and the fairings that covered the machine gun barrels in the aircraft’s nose.

Fisher was already engaged by the government to build large assembles for the North American B-25 Mitchell bomber, and plans for the manufacture of other aircraft components were in the works. It made sense to have a prominent aeronautical engineer as part of Fisher’s staff. In March 1942, Fisher was tasked to build various components (engine cowlings, outer wing panels, ailerons, flaps, horizontal stabilizers, elevators, vertical stabilizers, rudders) of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress and 200 complete aircraft. A new plant in Cleveland, Ohio would be built to support this order. Beyond Fisher, a number of other GM divisions were involved in building aircraft and aircraft engines under license from other manufacturers. However, GM wanted to design and manufacture its own products to support the war effort. Berlin was a believer in applying automotive methods to produce aircraft, which was a good match for the automotive giant GM.

On 10 September 1942, GM, through Fisher, submitted a proposal to the Army Air Force (AAF) for a new interceptor fighter. The proposal was based on an AAF request from February 1942 for such an aircraft with exceptional performance. The aircraft from Fisher was designed by Berlin, powered by an Allison V-3420 24-cylinder engine, and constructed mainly of components from other aircraft. The aircraft offered impressive performance with a top speed of 440 mph (708 km/h) at 20,000 ft (6,096 m), a 5,600 fpm (28.5 m/s) initial climb rate, a service ceiling of 38,000 ft (11,582 m), and a range of 2,240 miles (3,605 km) with only internal fuel. All of this came with a promise to deliver the first aircraft within six months of the contract being issued.

The top image shows at least five XP-75A aircraft under construction. The middle image, from right to left, shows the first two XP-75 aircraft (43-46950 and 43-46951) and the first two XP-75A aircraft (44-32161 and 44-32162). The second XP-75 (second from the right) has the wide H-blade propellers installed, while the other aircraft have the narrow A-blade propellers. The bottom image is a P-75A under construction. Note the V-3420 engine. (Veselenak Photograph Collection / National Museum of the US Air Force images)

Back in February 1941, the Army Air Corps (name changed to AAF in June 1941) had considered the Allison V-3420 as a possible replacement for the Wright R-3350 engine intended for the B-29. The Allison Engineering Company was a division of GM, and at the time, development of the V-3420 was focused on creating the basic engine and not much more. However, the priority of the V-3420 program was scaled-back after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941.

GM had been searching for an application for its Allison V-3420 engine, and the AAF had tried to entice other manufactures to incorporate the engine in a fighter design. Fisher’s fighter project offered a solution for both entities. The AAF was sufficiently impressed with Fisher’s proposal, and they approved the construction of two prototypes (serials 43-46950 and 43-46951) on 10 October 1942. The aircraft was given the designation P-75 Eagle, with the prototypes labeled XP-75. Some believe the pursuit number “75” was issued specifically at Berlin’s request, as his “Model 75” at Curtiss-Wright became the successful P-36 and led to the P-40. Although there were some reservations with the aircraft’s design, it was believed that a team working under the experienced Berlin would resolve any issues encountered along the way.

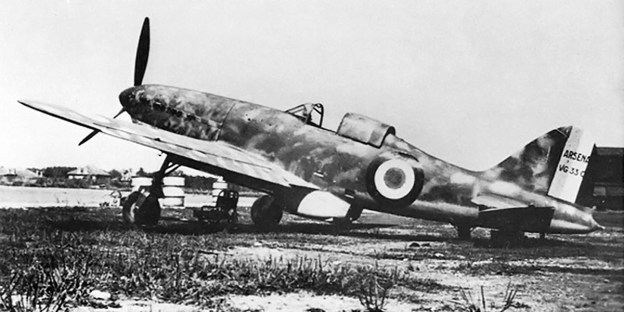

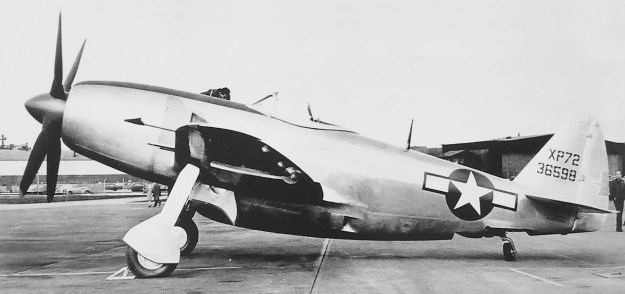

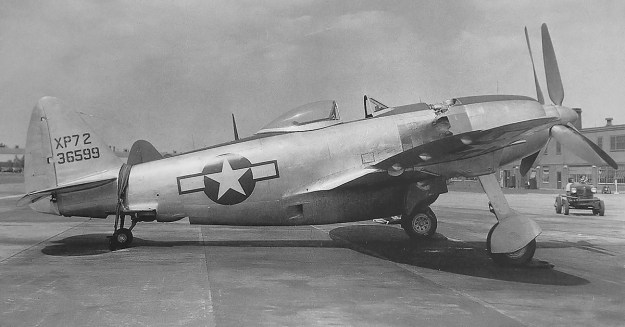

Aircraft 44-32162 was the fourth of the XP-75-series and the second XP-75A with additional wing fuel tanks. Note the revised canopy and tail compared to the first prototype. The aircraft has narrow A-blade propellers, and the 10-gun armament appears to be installed.

The XP-75 was of all metal construction with fabric-covered control surfaces. The cockpit was positioned near the front of the aircraft and provided the pilot with good forward and downward visibility. The pilot was protected by 177 lb (80 kg) of armor. The cockpit canopy consisted of front and side panels from a P-40. The aircraft’s empennage, with a fixed tailwheel, was from a Douglas A-24 Banshee (AAF version of the Navy SBD Dauntless). Initially, North American P-51 Mustang outer wing panels would attach to the inverted gull wing center section that was integral with the fuselage. However, the P-51 wings were soon replaced by wings from a P-40 attached to a normal center section. The main landing gear was from a Vought F4U Corsair, and it had a wide track of nearly 20 ft (6.10 m). Four .50-cal machine guns were mounted in the aircraft’s nose and supplied with 300 rpg. Each wing carried three additional .50-cal guns with 235 rpg. Under each wing, inside of the main gear, was a hardpoint for mounting up to 500 lb (227 kg) of ordinance or a 110-US gal (416-L) drop tank.

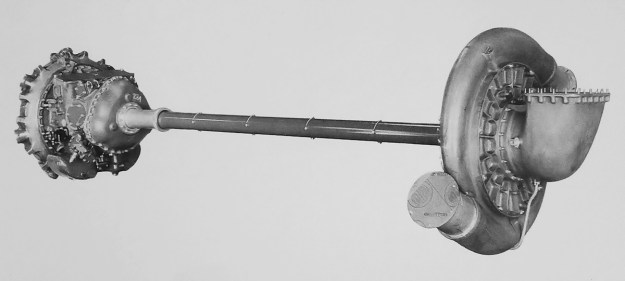

The 2,600 hp (1,939 kW) Allison V-3420-19 engine with a two-stage supercharger was positioned in the fuselage behind the pilot. Each of the engine’s four cylinder banks had an air-cooled exhaust manifold with two exhaust stacks protruding out of the fuselage. Two extension shafts passed under the cockpit and connected the engine to the remote gear reduction box for the Aeroproducts six-blade contra-rotating propeller. Two different types of propellers were used. Initially, a 13 ft (3.96 m) diameter, narrow, A-blade design was used. Many sources state that this propeller was used on the first 12 aircraft. However, some of these aircraft flew with the second design, a 12 ft 7 in (3.84 m) diameter, wide, H-blade. The gear reduction turned the propeller at .407 crankshaft speed.

The empennage (left) and inverted wings and fuselage (right) of XP-75A 44-32161 after its crash on 5 August 1944. An engine explosion and inflight fire led to the empennage separating from the rest of the aircraft. Russell Weeks, the pilot, was able to bail out of the stricken aircraft. (Veselenak Photograph Collection / National Museum of the US Air Force images)

A two-section scoop was located under the fuselage, just behind the wings. The left section held an oil radiator, and coolant radiators were positioned in both the left and right sections. The aircraft’s oil capacity and coolant capacity were 28.5 US gal (108 L) and 31.5 US gal (119 L) respectively. A 485-US gal (1,836-L) fuel tank was positioned in the fuselage between the cockpit and engine. The tank was made of two sections with the extension shafts passing between the sections.

An XP-75 mockup was inspected by the AAF on 8 March 1943. On 6 July, six additional prototypes (serials 44-32161 to 44-32166) were ordered with some design modifications, including changes to the cockpit canopy, the use of a 2,885 hp (2,151 kW) V-3240-23 engine, and additional fuel tanks in each wing with a capacity of 101 US gal (382 L). The extra fuel enabled the P-75 to cover the long-range escort role, something that the AAF was desperately seeking. The long-range fighter prototypes are often referred to as XP-75As, although this does not appear to be an official designation.

This image shows either 44-32165 or 44-32166 being completed in the Cleveland plant. These two aircraft, the last of the XP-75As, had a bubble canopy, retractable tailwheel, and a new, tall rudder and vertical stabilizer. Note the P-40-style rounded wings. (Veselenak Photograph Collection / National Museum of the US Air Force image)

Since the need for interceptors had faded, many in the AAF were optimistic that the long-range P-75 would be able to escort bombers all the way into Germany and that the aircraft would be able to outperform all German fighters for the foreseeable future. The P-75 also served as insurance if the P-51 and Republic P-47 Thunderbolt could not be developed into long-range escort fighters.

On 8 July 1943, a letter of intent was issued for the purchase of 2,500 P-75A aircraft (serials 44-44549 to 44-47048), but a stipulation allowed for the cancellation of production if the aircraft failed to meet its guaranteed performance. A definitive contract for all of the XP-75 work was signed on 1 October 1943 and stipulated that the first XP-75 prototype would fly by 30 September 1943, and the first long-range XP-75A prototype would fly by December 1943. The first production aircraft was expected in May 1944, and production was forecasted to eventually hit 250 aircraft per month. The production costs for the 2,500 P-75A aircraft was estimated at $325 million.

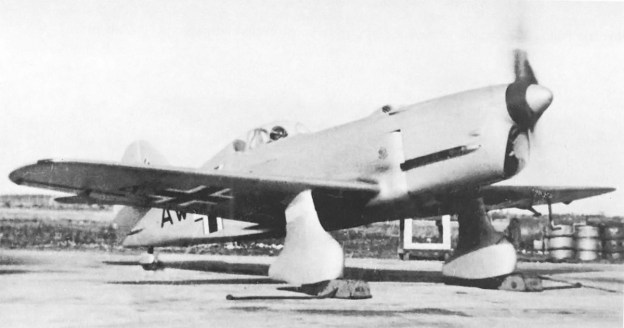

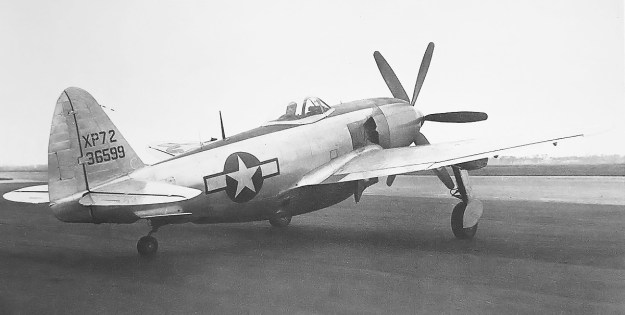

XP-75A 44-32165 with the new (and final) large, angular tail and horizontal stabilizer. However, the aircraft retained the rounded wings. Note the ventral strake behind the belly scoop, and the wide H-blade propellers. The same modifications were applied to 44-32166. The stenciling under the canopy says “Aeroproducts Flight Test Ship No 4.”

The Fisher XP-75A had a wingspan of 49 ft 1 in (14.96 m), a length of 41 ft 4 in (12.60 m), and a height of 14 ft 11 in (4.55 m). The aircraft’s performance estimates were revised to a top speed of 434 mph (698 km/h) at 20,000 ft (6,096 m) and 389 mph (626 km/h) at sea level. Its initial rate of climb was 4,200 fpm (21.3 m/s), with 20,000 ft (6,096 m) being reached in 5.5 minutes, and a service ceiling of 39,000 ft (11,887 m). The aircraft had an empty weight of 11,441 lb (5,190 kg) and a fully loaded weight of 18,665 lb (8,466 kg). With the fuselage tank, a total of 203 US gal (768 L) of fuel in the wings, and a 110-US gal (416-L) drop tank under each wing, the XP-75A had a maximum range of 3,850 miles (6,196 km).

The AAF gave the XP-75 priority over most of Fisher’s other work, particularly that of constructing 200 B-29 bombers. Construction of the first two prototypes was started at Fisher’s plant in Detroit, Michigan. The other six XP-75 aircraft were built at the new plant in Cleveland, Ohio, which opened in 1943. Production of the aircraft would occur at the Cleveland plant.

The production line with P-75A numbers two through four (44-44550 through 44-44553) under construction. While the aircraft have square wingtips, at least the first one still has the rounded horizontal stabilizer. Note the V-3420 engine by the first aircraft. The wing of an XP-75A is visible on the far right.

Flown by Russell Thaw, the XP-75 prototype (43-46950) made its first flight on 17 November 1943, and it was the first aircraft to fly with the V-3420 engine. Almost immediately the aircraft ran into issues: the center of gravity was off; the ailerons were heavy; the controls were sluggish; the aircraft exhibited poor spin characteristics; and the V-3420 engine was down on power and overheating. The trouble is not very surprising considering the aircraft consisted of parts from other aircraft and was powered by an experimental engine installed in an unconventional manner. The V-3420’s firing order was revised for smoother operation. Modifications to the second prototype (43-46951) included changes to the ailerons and a new rear canopy. The size of the rudder was decreased, but the surface area of the vertical stabilizer was increased by extending its leading edge. The second XP-75 prototype was completed in December 1943 and made its first flight on 27 January 1944.

The first of the six XP-75A long-range aircraft (44-32161) flew on 24 January 1944. The last two of these aircraft, 44-32165 and 44-32166, were finished with a bubble canopy and a new empennage. The new empennage had a retractable tailwheel and a taller vertical stabilizer and rudder. Lateral control was still an issue, and these two aircraft were later modified with larger and more angular vertical and horizonal stabilizers. These changes were also incorporated into most of the P-75A production aircraft.

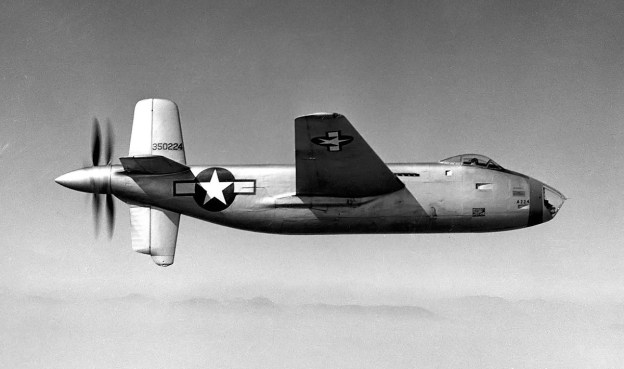

The first production P-75A (44-44549) with its square wingtips and original rounded tail. Note the ventral strake and the fins attached to the horizontal stabilizer. It is not known when the picture was taken (possibly 22 September 1944), but the aircraft and pilot were lost on 10 October 1944.

The third long-range XP-75A aircraft (44-32163) crashed on 8 April 1944, killing the pilot, Hamilton Wagner. The crashed may have been caused by the pilot performing unauthorized aerobatics. On 7 June 1944, the AAF issued the contract for 2,500 P-75A aircraft. Official trials were conducted in June 1944 and indicated that the XP-75A aircraft was well short of its expected performance. A top speed of only 418 mph (673 km/h) was achieved at 21,600 ft (6,584 m), and initial climb rate was only 2,990 fpm (15.2 m/s). However, the engine was reportedly not producing its rated output. On 5 August 1944, XP-75A 44-32161 was lost after an inflight explosion, which separated the empennage from the rest of the aircraft. The pilot, Russell Weeks, successfully bailed out.

In addition to other changes made throughout flight testing of the prototypes, the P-75As incorporated extended square wingtips with enlarged ailerons, the controls were boosted to eliminate the heavy stick forces, and a ventral strake was added that extended between the scoop exit doors and the tailwheel. The P-75A had a wingspan of 49 ft 4 in (15.04 m), a length of 41 ft 5 in (12.62 m), and a height of 15 ft 6 in (4.72 m). The aircraft’s performance estimates were revised down, with a top speed of 404 mph (650 km/h) at 22,000 ft (6,706 m). Its initial rate of climb dropped to 3,450 fpm (17.5 m/s), and the service ceiling decreased to 36,400 ft (11,095 m). The aircraft had an empty weight of 11,255 lb (5,105 kg) and a fully loaded weight of 19,420 lb (8,809 kg).

P-75A 44-44550 with the new (and final) square tail and horizontal stabilizer. Note the two-section belly scoop and the F4U main landing gear.

The first two P-75As (44-44549 and 44-44550) were not originally finished with the latest (angular) empennage. Rather, they used the tall, round version that was originally fitted to the last two XP-75A prototypes. A dorsal fillet was later added to the vertical stabilizer. The first Fisher P-75A (44-44549) took flight on 15 September 1944, with the second aircraft (44-44550) following close behind. Aircraft 44-44550 was later altered with the enlarged, square-tipped vertical and horizontal stabilizers, but it is not clear if 44-44549 was also changed. At some point (possibly late September 1944), aircraft 44-44549 had stabilizing fins added to the ends of its horizontal stabilizer. Both aircraft were sent to Eglin Field, Florida for trials. On 10 October 1944, aircraft 44-44549 was lost with its pilot, Harry Bolster. The crash was caused by the propellers becoming fouled by either a nose-gun tube failure or by part of the spinner breaking free. The damaged propellers quickly destroyed the gear reduction, and once depleted of oil, the propeller blades went into a flat pitch. Bolster attempted a forced landing but was not successful.

By the time of the last crash, the AAF had realized it would not need the P-75A aircraft. The P-51B/D and P-47D/N had proven that they were up to the task of being long-range escort fighters, and the war’s end was in sight. The P-75A was larger, heavier, slower, and sluggish compared to fighters already in service. The production contract for the 2,500 P-75As was cancelled on 6 October 1944, and further experimental work was stopped on 8 November. Five P-75A aircraft were completed, with an additional, nearly-complete airframe delivered for spare parts. Construction of approximately 20 other P-75A production aircraft had started, with some assemblies being completed.

A top view of 44-44550 provides a good illustration of the square wingtips and horizontal stabilizer. The wings were only slightly extended, but the area of the ailerons was increased by a good amount. The square extensions to the horizontal stabilizer increased its area significantly. Note that the machine gun armament is installed.

P-75A 44-44550 was later transferred to Moffett Field, California where it underwent tests on the contra-rotating propellers. The aircraft was scrapped after the tests. In an attempt to produce more power, a new intercooler was installed in 44-44551, and the aircraft was lent to Allison on 28 June 1945. Later, a 3,150 hp V-3420 was installed. Aircraft 44-44552 and 44-44553 were sent to Patterson Field, Ohio and stored for further V-3420 development work. None of the aircraft were extensively flown. The last completed P-75A, 44-44553, was preserved and is currently on display in the National Museum of the US Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. The aircraft went through an extensive restoration in 2008. All other P-75 aircraft were eventually scrapped.

The eight prototype aircraft had cost $9.37 million, and the manufacturing contract, including the six production aircraft, construction of the Cleveland plant, and tooling for production, had cost $40.75 million. This gave a total expenditure of $50.21 million for the 14 P-75 aircraft. In the end, the expeditious and cost-saving measure of combining existing components led to delays and additional costs beyond that of a new design. It turned out that the existing assemblies needed to be redesigned to work together, essentially making the P-75A a new aircraft with new components.

The pilot under 44-44550’s bubble canopy helps illustrate the aircraft’s rather large size. The P-75’s sluggish handling and lateral instability did not endear the aircraft to test pilots. Note the nearly-wide-open rear shutter of the belly scoop.

An often-cited story states that then Col. Mark E. Bradley, Chief of Aircraft Projects at Wright Field, was so dissatisfied with the XP-75 after making a test flight, that he requested North American add a large fuel tank in the fuselage of the P-51 Mustang. This act led to the ultimate demise of the XP-75 and the ultimate success of the P-51. However, that sequence of events is not entirely accurate.

Bradley initiated North American’s development of the P-51 fuselage tank in July 1943, after evaluating the XP-75’s design. Experiments with the P-51’s 85-gallon (322-L) fuselage tank were successfully conducted in August 1943. In early September 1943, kits to add the tank to existing P-51s were ordered, and about 250 kits arrived in England in November. At the same time, the fuselage tank was incorporated into the P-51 production line. These events preceded the XP-75 prototype’s first flight on 17 November 1943. Bradley’s later flight in the XP-75 solidified his view that the P-51 with the fuselage tank was the best and quickest option for a long-range escort, and that the XP-75, regardless of its progression through development, would not be superior in that role.

Fisher P-75A 44-44553 has been preserved and is on display in the National Museum of the US Air Force. (US Air Force image)

Sources:

– U.S. Experimental & Prototype Aircraft Projects Fighters 1939–1945 by Bill Norton (2008)

– Vees For Victory!: The Story of the Allison V-1710 Aircraft Engine 1929-1948 by Dan Whitney (1998)

– P-75 Series Airplanes Advance Descriptive Data (20 May 1944)

– P-51 Mustang: Development of the Long-Range Escort Fighter by Paul A. Ludwig (2003)

– Development of the Long-Range Escort Fighter by USAF Historical Division (1955)

– “Le Fisher XP-75 Eagle” by Alain Pelletier, Le Fana de l’Aviation (August 1996)

– “A Detroit Dream of Mass-Produced Fighter Aircraft: The XP-75 Fiasco” by I. B. Holley, Jr. Technology and Culture Vol. 28, No. 3 (July 1987)

– http://usautoindustryworldwartwo.com/Fisher%20Body/fisherbodyaircraft.htm

– http://www.alexstoll.com/AircraftOfTheMonth/3-00.html

– https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_accidents_and_incidents_involving_military_aircraft_(1943%E2%80%931944)