By William Pearce

On 17 May 1922 at Brooklands, England, Kenelm Lee Guinness set an official world land speed record* of 133.75 mph (215.25 km/h). This record was set in a Sunbeam racer, powered by a 350 hp (261 kW) Sunbeam Manitou V-12 engine of 1,118 cu in (18.3 L) displacement. This car was later sold to Malcolm Campbell and became the first Blue Bird land speed record car. The Sunbeam Motorcar Company was very involved in record-breaking and racing at this time. At Sunbeam, Louis Coatalen and Vincenzo Bertarione designed a Grand Prix car, but it was never built. The design ended up being sold to Prince Djelaleddin (sometimes spelled Djelalledin).

A picture from 1924 of the Djelmo racer with Price Djelaleddin behind the wheel and Giulio Foresti at right. The racer was painted light blue. Note the narrow track of the rear wheels.

The Egyptian Prince Djelaleddin lived in Paris, France and had an interest in setting a new land speed record. He hired Edmond Moglia, an Italian engineer living in Paris, to build the Sunbeam-designed racer for an attempt on the record. This new car was named Djelmo (a combination of Djelaleddin and Moglia’s names) and was built under a fair amount of secrecy.

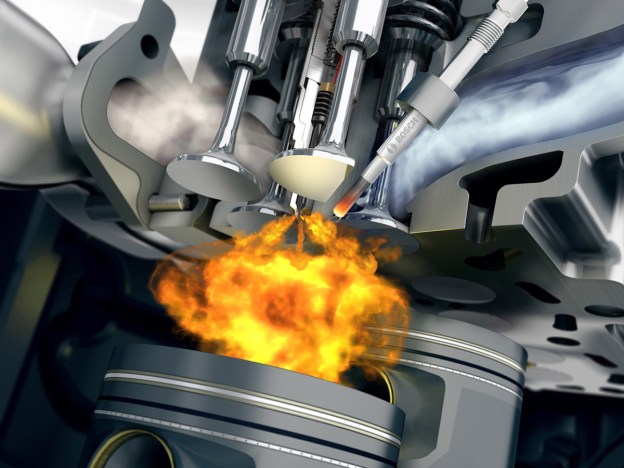

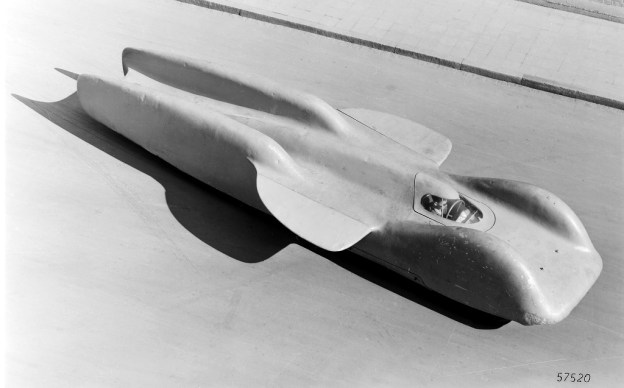

The Djelmo was a narrow and streamlined racer of a conventional layout, with the engine in front of the driver. The car was powered by a straight eight-cylinder engine with a 4.2 in (107 mm) bore and a 5.5 in (140 mm) stroke, for a total displacement of 615 cu in (10.1 L). Aluminum pistons were used, and the engine had a compression ratio of six to one. The cylinders were cast in two blocks of four. The two intake and two exhaust valves per cylinder were actuated by dual-overhead camshafts. The one-piece crankshaft was supported by nine main bearings. On the right side of the engine, one carburetor fed each pair of cylinders. On the left side, the eight exhaust stacks converged into one large pipe that exited low and just before the cockpit. Even though this engine was much smaller than the Manitou, it produced 355 hp (265 kW) when run at 3,000 rpm.

The Djelmo racer during what is believed to be its first public appearance. This image predates the one above, and reportedly, the racer was painted dark blue.

Three mounts were cast on each side of the engine’s crankcase. The rear mounts acted as the clutch housing to which the gearbox was mounted. The gearbox had two forward speeds and one reverse speed—the reverse gear was to satisfy French regulations. From the gearbox, power was sent to the rear wheels via a driveline geared directly to the rear axle; there was no differential. The rear wheels had a narrow track of only 37.4 in (.95 m). The front wheels had a much wider track of 58.3 in (1.48 m). The steering box and steering wheel were mounted to the top of the gearbox. To slow the Djelmo, a pedal worked a drum brake on the left rear wheel, and a hand lever worked a similar brake on the right rear wheel. The racer’s wheel base was 10.2 ft (3.1 m) and it weighted 2,006 lb (910 kg).

A few pictures of the seemingly complete racer were circulated in 1924. The Italian Giulio Foresti was selected as the driver, and the Djelmo was supposed to be ready for a record run in the United States in 1925. However, the car’s development was protracted, and its performance did not live up to expectations. A few test runs were conducted at sites in France, but these were just tuning sessions, not record attempts. The Djelmo underwent modifications to improve its performance and handling. Various carburetor set-ups were tried, a new windscreen was installed, and the Djelmo’s cowl and rear deck were reworked. The installation of a remote supercharger driven from the driveline was considered but never carried out.

Foresti (at right) oversees oil being added to the Djelmo’s engine at Pendine Sands before a run on the beach. The integral front engine mount can be seen just below the oil can spout. Note the changes to the grill from the earlier images above.

By 1926, John Godfrey Parry-Thomas, in Babs, had increased the land speed record to 171.02 mph (275.23 km/h). It would be hard for the Djelmo to better this speed. In late 1926, Prince Djelaleddin set out to build a new car. The design was a progression of the Djelmo and called for two of the eight-cylinder engines to be placed in tandem with the driver in between. The front engine was to drive the front wheels and the rear engine the rear wheels. A double clutch and gear shift mechanism was to be used, all actuated by single controls. The estimated top speed of this racer was 250 mph (402 km/h).

By late 1927, Henry Segrave, in the Sunbeam 1000 HP “Mystery Slug,” had increased the land speed record to 203.79 mph (328.0 km/h). This speed was far beyond anything the Djelmo could hope for, despite its engine now producing between 400-450 hp (300-355 kW). Foresti had brought the Djelmo to Pendine Sands, Wales earlier that summer for some speed runs. He now focused on breaking the current British record of 174.88 mph (281.44 km/h) held by Campbell in his Napier-powered Blue Bird. Foresti was basically on his own and had no proper facilities in which to work on the Djelmo. This delayed the record attempt several months, as even minor replacement parts took hours or days to acquire. All the same, he became a fixture in the area and was welcoming to all visitors.

Foresti taking the Djelmo out on the beach. Note the racer’s revised windscreen and rear deck compared to the images from 1924.

On 26 November 1927, Foresti took the Djelmo out on the sands to make a few runs. As was typical, Foresti wore only goggles and no other protection. The Djelmo had exhibited a tendency to fishtail at high speeds. While travelling on the beach at around 150 mph (240 km/h), Foresti lost control. The Djelmo rolled several times, and Foresti was ejected from the racer. Miraculously, Foresti suffered only minor injuries and walked toward rescuers. The fact that he was ejected clear of the rolling Djelmo and into the soft sand probably saved his life. The Djelmo was destroyed. Prince Djelaleddin had lost interest in these speed projects: the Djelmo was never repaired and the twin-engine racer was never built.

*Tommy Milton set a United States speed record at 156.046 mph (251.132 km/h) in a twin straight-eight-powered Duesenberg on 27 April 1920. His accomplishment was not officially recognized as a world record.

Foresti, just leaving the cockpit, is ejected from the Djelmo as it rolls on the beach. Amazingly, Foresti suffered only minor injuries.

This article is part of an ongoing series detailing Absolute Land Speed Record Cars.

Sources:

– Land Speed Record by Cyril Posthumus and David Tremayne (1971/1985)

– The Land Speed Record 1920-1929 by R. M. Clarke (2000)

– “Prince Designs Sixteen Cylinder Racer,” The Ogden Standard-Examiner, 24 October 1926

– “An Amazing Escape,” The Illustrated London News, 3 December 1927

– http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sunbeam_350HP