By William Pearce

Rostislav Alexeyev (sometimes spelled Alekeyev) of the Central Hydrofoil Design Bureau (CHDB or Tsentral’noye konstruktorskoye byuro na podvodnykh kryl’yakh / TsKB po SPK) had been working out of the Krasnoye Sormovo Shipyard in Gorky (now Nizhny Novgorod), Russia since the 1940s. In the 1950s, Alexeyev began experimental work with ekranoplans (meaning “screen planes”), also known as wing-in-ground effect (WIG) or ground-effect-vehicle (GEV). His work led to the construction of the massive, experimental KM (Korabl Maket or ship prototype) ekranoplan in the mid-1960s.

The SM-6 was a 50-percent scale proof-of-concept vehicle for the A-90 Orlyonok ekranoplan. First flown in 1971, testing of the SM-6 continued until the mid-1980s.

As work on the KM was underway, the Soviet Navy expressed interest in a troop transport ekranoplan, and Alexeyev had started design studies of such a craft as early as 1964. In 1966, the decision was made to construct a 50-percent scale test model of the troop transport. The test ekranoplan was designated SM-6 (samokhodnaya model’-6 or self-propelled model-6).

The SM-6 had a flying boat-style stepped hull that was made of steel and aluminum. The two-place, side-by-side cockpit was near the front of the machine and covered with a large canopy. Two hydro-skis were placed under the hull: one under the nose (bow) and one under the wings. The hydraulically-actuated skis helped lift the craft out of the water as it picked up speed.

An undated image of the SM-6 on display at Lenin Square in Kaspiysk, Russia. The ekranoplan has since been removed, and its fate is unknown. However, another undated image shows the its derelict fuselage (hull) in a sorry state.

Mounted in the SM-6’s nose were two Milkulin RD-9B jet engines, each of which produced 4,630 lbf (20.6 kN) of thrust. The inlets for the engines were in the upper surface of the nose, and the nozzles protruded out the sides of the SM-6, just behind and below the cockpit. For takeoff, the jet nozzle of each engine was rotated down to increase air pressure under the craft’s wings (power augmented ram thrust). In cruise flight, the nozzles were pointed back for forward thrust.

The low-mounted wing had a short span and a wide cord, and had an aspect ratio of 2.8. Five flaps were attached along each wing’s trailing edge. The outer flaps most likely acted as flaperons, a combination flap and aileron, but definitive proof has not been found. The tip of each wing extended down to form a float. A large vertical stabilizer extended from the rear of the craft. A rudder was positioned on the trailing edge of the vertical stabilizer. When the SM-6 was on the water’s surface, the bottom part of the rudder was submerged and helped steer the craft. Mounted atop the tail was a 3,750 shp (2,796 kW) Ivchenko AI-20K turboprop engine driving a four-blade propeller that was approximately 12 ft (3.65 m) in diameter. Behind the engine and atop the tail was the large horizontal stabilizer with swept leading and trailing edges. Large elevators were incorporated into the trailing edges of the horizontal stabilizer.

The A-90 Orlyonok cruising above the Caspian Sea. The jet intakes positioned atop the bow helped reduce the amount of water ingested into the engines and kept the craft rather streamlined.

The SM-6 had a wingspan of 48 ft 7 in (14.8 m), a length of 101 ft 8 in (31.0 m), and a height of 25 ft 9 in (7.85 m). The craft had a cruise speed of 186 mph (300 km/h) and a maximum speed of 217 mph (350 km/h). Its operating height was from 2 to 5 ft (.5 to 1.5 m), and the SM-6 had a maximum weight of 58,422 lb (26,500 kg). The craft had a range of 435 miles (700 km) and could operate in seas with 3.3 ft (1.0 m) waves.

Construction of the SM-6 started in October 1966 at the Krasnoye Sormovo Shipyard. Insufficient funding caused some delays, and the SM-6 was not finished until 30 December 1970. At that time, the Volga Shipyard was established as an experimental production facility of the CHDB and operated out of the same plant in which the SM-6 was built. The CHDB was also renamed the Alekseyev Central Hydrofoil Design Bureau.

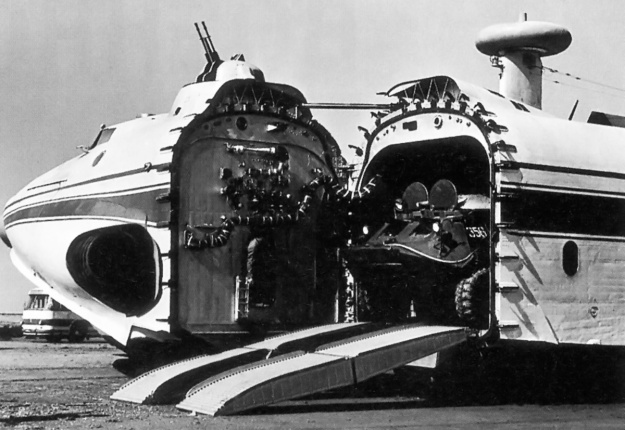

The entire front of the Orlyonok swung open to allow access to the cargo hold. A 22,708 lb (10,300 kg) BTR-60PB armored personnel carrier is seen loaded on the Orlyonok. Note the engine’s exhaust nozzle and the machine gun turret.

In July 1971, the SM-6 was transported about 53 miles (85 km) up the Volga River to Chkalovsk, Russia. Initial tests of the craft were conducted in August 1971 on the Gorky Reservoir. In early 1972, the SM-6 was successfully tested on ice and snow. In 1973, modifications were made that included mounting wheels to the hydro-skis. The wheels were used as beaching gear, allowing the SM-6 to power itself out of the water and onto land, or vice versa. Having proven itself as a fully functioning ekranoplan, the SM-6 was transferred to the Kaspiysk base on the Caspian Sea in late 1974. The SM-6 continued to undergo modifications and testing until the mid-1980s. At different points in its career, the SM-6 was marked as 6M79 and 6M80. After it was withdrawn from service, the SM-6 was displayed for a number of years at a public square (Lenin Square?) in Kaspiysk. The elements took a toll on the ekranoplan, and it was eventually removed from the square. The derelict remains of the SM-6 sat near the shore of the Caspian Sea for a time, and mostly likely, the machine was later scrapped.

Following the successful tests of the SM-6 in 1971, plans moved forward for constructing a full-scale, troop transport ekranoplan. The full-size ekranoplan was known as the A-90 Orlyonok (Eaglet) or Project 904. Although twice its size, the Orlyonok had mostly the same configuration as the SM-6.

The Orlyonok’s beaching gear allowed the craft to propel itself out of the water and onto a hard surface. The turning arc of the nose wheel has not been found, but with the main wheels under the wing, the Orlyonok may have been able to turn rather sharply on land.

Mounted in the Orlyonok’s nose (bow) were two Kuznetsov NK-8-4K jet engines that provided 23,149 lbf (103.0 kN) of thrust each. Just behind the craft’s cockpit was a turret with two 12.7-mm (.50-Cal) machine guns. The entire nose of the Orlyonok, including its cockpit, swung open to the right a maximum of 92 degrees. A set of folding ramps allowed for direct entry into the machine’s cargo hold, which was 68 ft 11 in (21.0 m) long, 9 ft 10 in (3.0 m) wide, and 10 ft 6 in (3.2 m) tall. The hold could carry 250 troops or 44,092 lb (20,000 kg) of equipment, including armored vehicles.

The beaching gear mounted to the hydro-skis consisted of a steerable, two-wheel nose unit and a ten-wheel main unit under the hull. The low-mounted wing had a short span and a wide cord, with an aspect ratio of 3.0. The trailing edge of the wing had flaperons at its tips with flaps spanning the rest of the distance. The tip of each wing extended down to form a float. A large vertical stabilizer extended from the rear of the craft. Mounted atop the tail was a 15,000 ehp (11,186 kW) Kuznetsov NK-12MK turboprop engine driving an eight-blade, contra-rotating propeller that was approximately 19 ft 8 in (6.0 m) in diameter. The Orlyonok was equipped with a full-range of navigational and combat electronics.

At low speed, a fair amount of spray enveloped the Orlyonok. The circular markings on the sides of the craft designated over-wing access doors, which were actually rectangular.

The Orlyonok had a wingspan of 103 ft 4 in (31.5 m), a length of 190 ft 7 in (58.1 m), and a height of 52 ft 2 in (15.9 m). The craft had a cruise speed of 224 mph (360 km/h) and a maximum speed of 249 mph (400 km/h). Operating height was from 2 to 16 ft (.5 to 5.0 m). The Orlyonok had an empty weight of 220,462 lb (100,000 kg) and a maximum weight of 308,647 lb (140,000 kg). The craft had a range of 932 miles (1,500 km) and could operate in seas with 6.6 ft (2.0 m) waves.

The Orlyonok prototype was built at the Volga Shipyard and made its first flight in 1972, taking off from the Volga River. The craft was later disguised as a Tupolev Tu-134 airliner fuselage and transported by barge to the Kaspiysk base on the Caspian Sea for further testing. In 1975, the prototype was accidently beached on a rocky sandbar. The craft was able to power itself back into the water, but the hull was damaged and its structural integrity was compromised. The damage went undetected until the rear fuselage and tail broke off during a landing on rough seas. Alexeyev was onboard and took control of the crippled ekranoplan. Using full-power of the bow jet engines, Alexeyev as able to keep the open back of the hull above water and return to base. The authorities attributed the accident to a design deficiency and blamed Alexeyev, who was removed as the chief designer and reassigned to experimental work.

The Orlyonok prototype flies past a Soviet Navy ship on the Caspian Sea. Unlike the SM-6, the Orlyonok’s rudder did not extend into the water when the craft was on the sea.

The Russian Navy had been sufficiently impressed by the Orlyonok to order three production machines and a static test article. The damaged prototype was returned to the Volga Shipyard and completely rebuilt as the first production Orlyonok, S-21 (610), which was completed in 1978 and delivered to the Navy on 3 November 1979. The second Orlyonok, S-25 (630), was completed in 1979 and delivered on 27 October 1981. The final Orlyonok, S-26 (650), was completed in 1980 and delivered on 30 December 1981. Plans to produce an additional eight units were ultimately abandoned.

The three Orlyonoks were tested and operated for several years on the Caspian Sea. The captain and crew of S-21 took it upon themselves to test the machine to its limits. Away from witnesses and in the middle of the Caspian Sea, S-21 was flown out of ground effect and up to 328 ft (100 m) for an extended time. At that height, the ekranoplan was sluggish, unstable, and a challenge to fly, but positive control was maintained.

Two production Orlyonoks at Kaspiysk on the Caspian Sea. Note the open over-wing doors and the open engine access panel of the first machine.

By 1989, the three Orlyonoks had performed a total of 438 flights and 118 beachings. On 12 September 1992, S-21 was lost when a control malfunction coupled with pilot error caused it to rise to 130 ft (40 m) and stall. One member of the ten-man crew was killed, and S-21 was eventually sunk by the Navy—the cost of salvaging the craft was too high. Reportedly, the last Orlyonok flight was made by S-26 in late 1993, after which, the Orlyonoks fell into a state of disuse followed by disrepair.

In 1998, the Navy wrote off the two remaining Orlyonoks. Around 2000, S-25 was scrapped, but S-26 was somehow preserved. In 2006, S-26 was given to the Museum and Memorial Complex of the History of the Navy of Russia (Muzeyno-Memorial’nyy Kompleks Istorii Vmf Rossii) located on the Volga River in Moscow. The S-26 was demilitarized in 2007 and restored and installed at the museum in 2008. The Orlyonok design inspired other military and commercial ekranoplan design, but none were built.

Orlyonok S-26 shortly after it was put on display at the Naval museum in Moscow. The wheels of the beaching gear are visible, although it appears the main set is missing two wheels. Sadly, the condition of the impressive ekranoplan has deteriorated over the years. (Alex Beltyukov image via Wikimedia Commons)

Sources:

– Soviet and Russian Ekranoplans by Sergy Komissarov and Yefim Gordon (2010)

– WIG Craft and Ekranoplan by Liang Lu, Alan Bliault, and Johnny Doo (2010)

– https://aviationhumor.net/the-last-flight-of-the-soviet-beach-assault-ekranoplan-a-90-orlyonok/#

– http://www.volga-shipyard.com/index.php?section=history&lang=eng

One more link with tech data & scheme (in Russian)

http://www.airwar.ru/enc/sea/orlenok.html

Thank You for such an in-depth and well-researched article on these forgotten engineering masterpieces. Incredible the wealth of information and high-resolution pictures you’ve been able to compile on such a rare topic. Genuinely appreciate the hard work you put into it