By William Pearce

In April 1926, the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company (Curtiss) initiated the design of a 600 hp (447 kW) air-cooled aircraft engine. The engine was of a “hexagonal” design, with six banks of two cylinders, and had a relatively small diameter. Known was the H-1640 Chieftain, the two-row engine experienced some cooling issues and was abandoned shortly after the merger of Curtiss with Wright Aeronautical (Wright) in July 1929.

The liquid-cooled Wright H-2120 was developed from the air-cooled Curtiss H-1640 Chieftain. The engine was designed when experiments with two-row radials had just begun and concerns existed about air-cooling being sufficient for the rear cylinders.

In 1930, the United States Navy (Navy) initiated a special “high-speed development program” to challenge the success achieved by foreign high-speed aircraft, especially those demonstrated in the 1929 Schneider Trophy contest. Wright resurrected the hexagon engine design to further exploit its relatively small diameter. Using the H-1640 as a foundation, a liquid-cooled engine with an increased bore and stroke was designed by Wright. The new six-bank engine was to ultimately have four cylinders per bank, giving the 24-cylinder engine a displacement of 4,240 cu in (69.5 L) and an output of over 2,000 hp (1,491 kW). However, development was initiated with just two cylinders in each bank, and the 12-cylinder engine was known as the H-2120.

In June 1931, the Navy issued Contract No. 22625 to Wright for the development of two 1,000 hp (746 kW) H-2120 engines. From these developmental engines, a service type was to be derived. The Navy, always with an interest in air-cooled engines, stipulated that an air-cooled version was to be developed as either a companion to or a replacement of the liquid-cooled version. The Navy felt the air-cooled H-2120 could serve as competition and a backup to the 870 hp (649 kW), air-cooled, 14-cylinder Pratt & Whitney R-2270 radial, which was under development.

In a sense, the Wright H-2120 was three V-4 engines on a common crankcase, which created its hexagonal shape when viewed from the front. The two-row engine had an aluminum, three-piece crankcase that was split vertically at the centerline of the cylinders. The crankcase sections were secured together with bolts positioned between the cylinder banks. The single-piece, two-throw, crankshaft was supported by three main bearings. An odd connecting rod arrangement consisted of one blade rod, four articulated rods, and one fork rod. However, the blade and fork rod moved as a unit, as the pins that held the articulated rods passed through both the blade rod and the fork rod. The connecting rod arrangement was referred to as having dual master rods, with both the blade rod and fork rod technically considered master rods.

With six cylinder banks, the front view of the H-2120 illustrates its hexagonal shape. Note the coolant manifolds at the front of the engine.

The cylinder banks were spaced at 60-degree intervals around the crankcase, with the left and right banks perpendicular to the engine. The individual cylinders had a steel barrel surrounded by a steel water jacket. Each cylinder pair that formed a bank had a common cylinder head. Each cylinder had two intake valves and two exhaust valves, all actuated by dual overhead camshafts. The camshafts for each cylinder bank were geared to a vertical shaft driven from the front of the engine. The cylinders had a compression ratio of 6.5 to 1.

Mounted to the front of the engine was a planetary gear reduction that turned the propeller shaft at .6875 times crankshaft speed. At the rear of the engine was a single-speed supercharger that turned at 5.45 times crankshaft speed. Air was drawn through a downdraft carburetor, mixed with fuel, and compressed by the supercharger’s 11 in (279 mm) impeller. The air and fuel mixture was distributed to each of the six cylinder banks by a separate manifold. Each manifold had four short runners to deliver the charge to each cylinder’s two intake ports. The cylinder banks were arranged so that their intake and exhaust sides were mirrored with the adjacent cylinder banks. Each cylinder’s two spark plugs were fired by magnetos positioned at the rear of the engine. Coolant for the top four cylinder banks was circulated up from the base of each cylinder water jacket and through the cylinder head. Coolant for the lower two cylinder banks was the reverse—it flowed through the inverted head and up to the base of the water jacket.

The Wright H-2120 had a 6.125 in (156 mm) bore, a 6.0 in (152 mm) stroke, and a total displacement of 2,121 cu in (34.76 L). The engine had a sea level rating of 1,000 hp (746 kW) at 2,400 rpm with 2.2 psi (.16 bar) of boost, and it had a takeoff rating of 1,100 hp (820 kW). The H-2120 was 49 in (1.24 m) in diameter and was 57 in (1.45 m) long. The engine weighed 1,440 lb (653 kg).

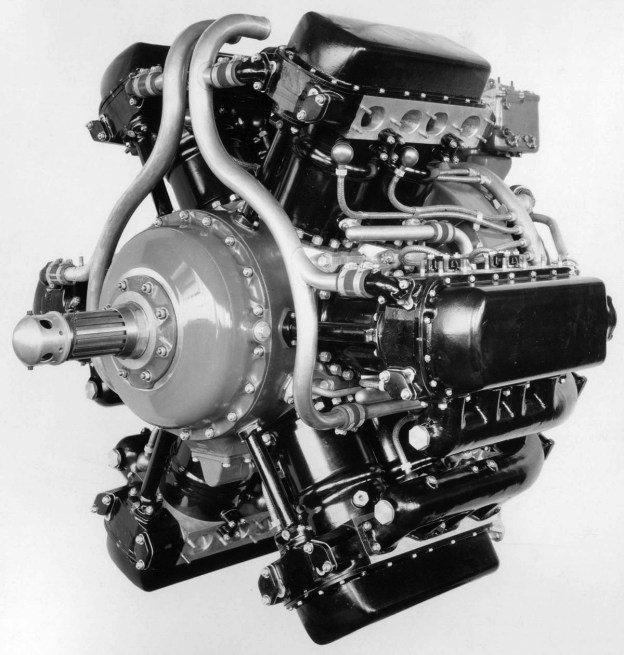

Side view of the first H-2120 illustrates the relatively short length of the engine. Note the supercharger housing and the intake manifolds.

The first H-2120 engine carried the Wright Manufacture’s No. 11691 and the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics No. (BuNo) 0120. The BuNo is often incorrectly recorded as 0210 or 0119 in Wright and Navy documentation. The H-2120 engine encountered issues that delayed its development. The issues were mainly focused on the connecting rod arrangement. Several different connecting rod arrangements were tested and discarded before the dual master rod type was adopted. The engine was first run in late 1933 or early 1934. It failed a 50-hour endurance test conducted by Wright in January 1935, but the cause of the failure has not been found. The test involved 10 cycles of running the engine for 30 min at 1,000 hp (746 kW) and 4.5 hours at 900 hp (671 kW). The endurance test was rerun, and the H-2120 passed on 10 May 1935.

The Army Air Corps (AAC) was seeking an engine capable of 1,250 hp (932 kW) for takeoff and had been following the development of the H-2120. Starting around January 1935, the Navy and Wright began to share information on the engine’s development with the AAC. In August 1935, progress on the engine had again slowed, and the AAC asked the Navy if it could assist with H-2120 testing and development. The Navy had planned to use the first engine for bench testing and the second engine for at least 25 hours of flight tests. By early September, the first engine was in the middle of a 50-hour Navy type test, with other tests yet to be conducted. The Navy had lost interest in the liquid-cooled engine and was planning to convert the second engine to air-cooling after the 25 hours of flight trials. The conversion was expected to involve just new cylinders and valve gear. If all went well, two additional air-cooled engines would be ordered that incorporated whatever changes were deemed desirable from the previous tests. The second engine was Manufacture’s No. 11692 / BuNo 0121, and it was undergoing its initial test runs after assembly at Wright.

In response to the AAC’s request, the Navy proposed that it continue tests with the first engine, and the second engine would be delivered to the AAC for flight tests. If the AAC wanted to test the engine beyond the 25 hours, they were free to do so. If the engine showed promise, the Navy would order a small number of air-cooled versions. The AAC agreed to these terms, provided they could do some preliminary engine tests before the H-2120 was installed in an aircraft.

Rear view of the engine shows the downdraft carburetor, two magnetos, generator, and starter. Water pumps were located at the bottom of the engine.

By the end of September 1935, testing had included 200 hours of single cylinder tests, and the first H-2120 had completed 56 hours at 1,000 hp (746 kW), 44 hours at 900 hp (671 kW), and 140 hours of calibration and miscellaneous tests. A 50-hour Wright endurance test and a 50-hour Navy type test had been completed. During the Navy test, which was completed on 15 September 1935, four leaks had developed in the water jackets, one camshaft broke, and one valve guide had cracked. The Navy wanted to complete a 150-hour test. The two 50-hour tests counted for 100 hours, and the 140 hours of calibration counted for 25 hours. Wright offered to complete at their own expense the final 25 hours of the 150-hour test. This included 15 hours alternating between 1,100 hp (820 kW) takeoff power and idle, and 10 hours at 1,000 hp (746 kW) and 110% maximum engine speed (2,640 rpm).

On 7 November 1935, the AAC received the second H-2120 engine. The AAC had selected a Bellanca C-27A single-engine transport to serve as the H-2120 test bed. The engine’s installation would add 860 lb (390 kg) to the aircraft. After further evaluation, it was determined that the center of gravity would be out of limits, and the C-27A was deemed unsuitable for the engine tests. A Fokker C-14A was substituted, and serial number 34-100 was assigned for the conversion on 15 November.

Testing of the first engine at Wright had run into issues. After 4.5 hours at 2,640 rpm, an intake valve failed, resulting in a severe backfire. During inspection, the blower housing was found to be cracked, the crankcase had been punctured, and several connecting rods were damaged. Some of the damaged connecting rods were a result of improper assembly. The engine was repaired but damaged again on 20 November, when anther intake valve failed after 3.25 hours at 2,640 rpm. Before the failure, the H-2120 was producing 1,168 hp (871 kW) with a coolant and oil outlet temperature of around 255 ℉ (124 ℃). The engine was repaired again and completed its 10 hours at 2,640 rpm on 23 December 1935. The first H-2120 was retained by Wright for further tests.

By the end of December 1935, the AAC had run in the second engine for five hours and up to 2,300 rpm. The fuel pump diaphragm failed four times, necessitating replacement of the pump. After some vibration issues were overcome, calibration tests were started in mid-January 1936. The AAC concluded its tests in April, stating that the second H-2120 ran smoothly. The engine produced 1,000 hp (746 kW) at 2,400 rpm with 1.8 psi (.12 bar) of boost. It also developed 1,139 hp (849 kW) at 2,550 rpm with 3.2 psi (.22 bar) of boost. Installation of the H-2120 in the C-14A was forecasted to add 800 lb (363 kg), and the AAC felt that more information could be gained by continued ground testing rather than flight tests in the C-14A.

The first H-2120, Manufacture’s No. 11691 / BuNo 0120 appears to be complete. It is not known if it was repaired after its rear connecting rod failure. (NASM image)

Meanwhile, testing of the first H-2120 had continued at Wright. On 20 February 1936, the blade connecting rod on the rear crankpin failed during calibration for a 20-hour test at takeoff power (1,100 hp / 820 kW). The failure was the result of fatigue, and the broken rod caused significant damage to all nearby components.

In May 1936, Wright informed the AAC and Navy of a secret air-cooled engine that is had been developing at its own expense. This engine was expected to have an initial sea level rating of 1,200 hp (894 kW) and a takeoff rating of 1,400 hp (1,044 kW). Wright offered the services an experimental version of the engine for $38,750, with delivery expected in early 1937. Wright did not want any details of this engine leaked to its competitors and asked that the AAC and Navy refer to it as the “Aircooled 2120,” even though that was not the engine’s displacement. Wright felt that this new engine, which was the 14-cylinder R-2600 radial, possessed more potential than the H-2120. Wright wanted to drop further H-2120 development to focus on the R-2600. Both the AAC and the Navy agreed, encouraged Wright to continue R-2600 development, and stated their intention of purchasing experimental examples once money for the 1937 budget was available. The Navy had already lost interest in the H-2120, and the AAC stopped further testing in July.

During the fall of 1935, the Boeing Airplane Company, the Curtiss Aeroplane & Motor Company, and the Glenn L. Martin Company all requested data on the H-2120 so that they could potentially incorporate the engine into designs they were working on. Since the H-2120 was a joint project at the time, the service that received the request would check with the other service to see if there were any objections to sharing information. The only company denied data was North American Aviation, which requested information in January 1936. Both the AAC and Navy said they had no projects with the company that required an engine like the H-2120. Despite the interest, no applications for the H-2120 have been found.

Both H-2120 engines survive and are held in storage by the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. The first engine, Manufacture’s No. 11691 / BuNo 0120, is complete. It is not known if it was fully repaired after the failure of the rear connecting rod, or just reassembled. The second H-2120, Manufacture’s No. 11692 / BuNo 0121, was sectioned to expose its inner workings. The H-2120 represented the last of the hexagonal engines from the United States. Other hexagonal engines include the Curtiss H-1640, the SNCM 137, the Junkers Jumo 222, and the Dobrynin series of aircraft engines.

The second H-2120, Manufacture’s No. 11692 / BuNo 0121, neatly sectioned and displaying its internals. Note the four valves per cylinder and odd connecting rods. (NASM image)

Sources:

– Numerous documents held by the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration at College Park, Maryland under Record Group 342 – Air Force Engineering Division RD 1676 and 3285 (scanned by Kim McCutcheon of the Aircraft Engine Historical Society)

– Development of Aircraft Engines and Aviation Fuels by Robert Schlaifer and S. D. Heron (1950)

– https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/wright-ch-2120-radial-12-engine/nasm_A19731548000

– https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/wright-xr-2120-radial-12-engine-cutaway/nasm_A19710896000