By William Pearce

Robert Esnault-Pelterie was born in France on 8 November 1881. In the early 1900s, he began experimenting with a glider modeled after the Wright Brothers’ glider of 1902. Esnault-Pelterie had experienced trouble with the Wrights’ wing warping technique and switched to ailerons in 1903. In 1906, Esnault-Pelterie began constructing a powered aircraft of his own design as well as an engine to power it. Esnault-Pelterie named the aircraft the R.E.P. 1 and it first flew in 1907. A new feature of the aircraft was a control stick, which Esnault-Pelterie patented. That patent made Esnault-Pelterie a rich man once royalties were paid after World War I. While the unique engine that he designed was the first in a family of engines known as R.E.P., their success would not endure like that of the control stick.

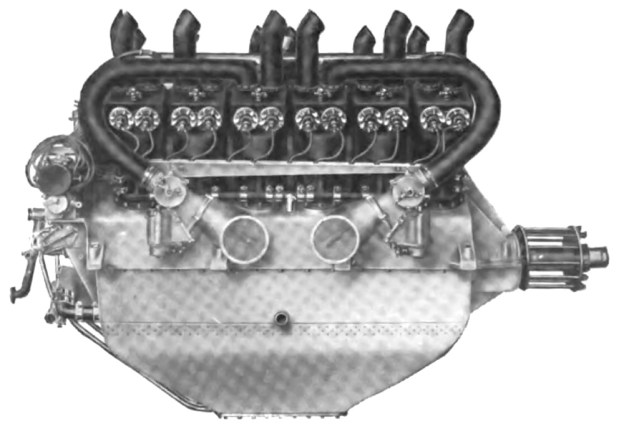

Front view of the R.E.P. seven-cylinder fan engine. Exhaust gases flowed out the holes around the top of the cylinders. The intake manifold can barely be seen behind the cylinders. In this view, the four cylinders on the right shared an intake manifold as did the three cylinder on the left.

Esnault-Pelterie’s first engine was an air-cooled, seven-cylinder fan engine. Sometimes referred to as a semi-radial, this engine had cylinders that were fanned-out on the top of the crankcase and not positioned around its entirety like a true radial. The cylinders were arranged in two rows—the front had four cylinders, and the rear had three cylinders. This configuration solved lower cylinder lubrication issues of radial engines, and air-cooling issues of inline engines.

The cast iron cylinders were attached to an aluminum crankcase. The upper part of the cylinder had cooling fins to dissipate heat. At the very top of the cylinder was a large, single valve. The valve was shaped like a piston and inverted, with the valve stem attached to underside of the head. When the valve was completely closed, a flange on its head would seat against the cylinder head and seal the cylinder. When the valve was partially open, exhaust gases flowed around the flange and escaped through ports in the cylinder head. When the valve was completely open, ports in its sides aligned with ports in the cylinder head to allow the intake mixture to flow into the cylinder.

In this section view of the R.E.P. seven-cylinder engine, the cylinders are numbered by firing order. Cylinder 5 has the intake/exhaust valve completely closed. Cylinder 1 shows the valve partially open to allow exhaust gases to exit the cylinder. Cylinder 2 shows the valve completely open to allow the air/fuel mixture into the cylinder. Note the master/articulated connecting rod arrangement.

The valve was actuated by a rocker arm attached to the cylinder. The rocker arm was moved via a pushrod that was operated by a cam ring inside the engine. Each row of cylinders had its own cam ring positioned at the rear of the engine, and the cam rings had stepped lifts. The first step opened the valve part way to allow the exhaust gases to vacate the cylinder. The second, higher lift completely opened the valve to allow the fresh air/fuel mixture into the cylinder. For the intake, the cylinders were separated into left and right groups, with the left group (when viewing the engine from the rear) having an additional cylinder. Each group shared a common intake manifold with a carburetor attached to its end. The intake manifold was attached to the upper rear of the cylinder. Exhaust gases flowed out though ten holes around the cylinder’s top; there were no exhaust stacks.

A single spark plug was installed in the side of the cylinder and fired by an ignition coil powered by a battery. The pistons were made of steel and had two oil rings. They were attached to the connecting rods by trunnions bolted to the underside of the piston. The connecting rod for each row of cylinders had one master rod, and the rest were articulating rods. The crankshaft had two throws offset 180 degrees and was supported by two main bearings. To balance the crankshaft, Esnault-Pelterie left the crankpin solid for the row with an additional cylinder, and the crankpin for the row with one fewer cylinder was drilled hollow.

This side view of the R.E.P. 10-cylinder engine illustrates how it was comprised of two five-cylinder engines bolted front-to-front. Note the rocker arm arrangement and the single valve. The pictured engine was equipped with magnetos.

The engine had a 3.35 in (85 mm) bore and 3.74 in (95 mm) stroke. The seven cylinders displaced a total of 230 cu in (3.8 L). The engine produced 30 hp (22 kW) at 1,500 rpm and weighed 150 lb (68 kg). A five-cylinder version was also built with three cylinders in the first row and two in the second. It produced 20 hp (15 kW) at 1,500 rpm from its 164 cu in (2.7 L) and weighed 118 lb (54 kg). Another version consisted of two five-cylinder engines joined at their front to create a 10-cylinder engine. Each engine group had its own intake manifold feeding five cylinders. The 10-cylinder engine produced 50 hp (37 kW) at 1,500 rpm from its 329 cu in (5.4 L) and weighed 214 lb (97 kg). Some sources indicate the same coupling treatment was applied to the seven-cylinder engine to create a 14-cylinder engine, but this cannot be confirmed. A 14-cylinder engine would have displaced 461 cu in (7.5 L) and produced around 70 hp (52 kW).

The five- and seven-cylinder engines powered a number of early aircraft (R.E.P.s, Bléroits, Kapferer-Paulhans, and Breguets), but it is unlikely the 10-cylinder engine ever flew. Esnault-Pelterie received an award in 1908 from the Société des ingénieurs civils de France (Society of Civil Engineers of France) for his seven-cylinder R.E.P. engine. However, the cylinder’s single valve proved unsatisfactory, and the engines were redesigned in 1909.

Rear view of the R.E.P. 10-cylinder engine equipped with a coil ignition. Note that each engine section has its own intake manifold and carburetor.

The updated engines had two valves per cylinder, but they were still operated by a single rocker arm. The intake valve was in the front of the cylinder, and the exhaust valve was in the rear. The rocker arm pivoted between the valves so that it pushed the intake valve open and then rocked back to pull down on the exhaust valve to open it. This was achieved by a grooved cam-disc that could “pull” and “push” the pushrod.

The engine’s bore and stroke were increased to 3.94 in (100 mm) and 5.51 in (140 mm). The five-cylinder engine displaced 335 cu in (5.5 L) and produced 60 hp (45 kW) at 1,400 rpm. The seven-cylinder engine displaced 470 cu in (7.7 L) and produced 90 hp (67 kW) at 1,400 rpm. There is no indication that any attempt to couple the engines was made. The cylinders had revised cooling fins, and the spark plug was repositioned to the cylinder head. Magnetos were used in place of the coil ignition.

An updated R.E.P. five-cylinder engine preserved in a R.E.P. Type D monoplane at the Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace. Note the two valves per cylinder and rocker arm arrangement. The unique induction system can be seen in which it drew air from the crankcase and delivered it to the cylinders via the copper pipes. The individual exhaust pipes can be seen at the rear of the engine. (John Martin image via the Aircraft Engine Historical Society)

Induction and exhaust were also updated. Intake air was fed from the crankcase (where it was warmed), through a distributor, and then to the front of each cylinder. Exhaust gases were collected in pipes at the rear of each cylinder and directed away from the cockpit. The many changes increased the weight of the engines to 243 lb (110 kg) for the five-cylinder and 287 lb (130 kg) for the seven-cylinder. The updated R.E.P. fan engine had no trouble running for 10 hours non-stop during various bench tests.

The five-cylinder engine seemed the more successful of the two and was installed in a number of aircraft (R.E.P.s and Farman-Neubauers). It was used in the Vickers R.E.P., which was the first aircraft made by Vickers and would have been the first aircraft to fly in Antarctica had its wings not been damaged during a demonstration flight in Australia. Even so, the wingless Vickers was taken to Antarctica and used as a powered sled, but with not much success. The remains of this aircraft were rediscovered there in January 2010.

The Vickers R.E.P. in Antarctica in 1911. The engine clearly has two valves per cylinder and the unique induction system of the updated fan engine.

In 1911, Esnault-Pelterie refocused his design efforts on true radial engines, constructing five- and seven-cylinder engines. The fan/semi-radial engines were phased out in 1912. Over the next few years, Esnault-Pelterie stopped designing piston engines as he became more interested in rocketry. A few R.E.P. fan engines still exist in museums, including a seven-cylinder engine in Esnault-Pelterie’s original R.E.P. 1 aircraft from 1907 displayed at the Musée national des Arts et Métiers (National Museum of Arts and Crafts) in Paris, France. This museum may also hold another original seven-cylinder engine cutaway. An updated five-cylinder engine exists installed in an uncovered R.E.P. Type D monoplane from 1910 at the Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace (Air and Space Museum) in Le Bourget, France.

Note: Many sources list a variety of different bore and stroke combinations for the R.E.P. fan engines. Some sources list some of the early engines as having a 3.54 in (90 mm) stroke, while others list the updated engines as having a 4.33 in (110 mm) bore or 6.30 in (160 mm) stroke. While it is possible that such bore and stroke combinations were built, little supporting information has been found.

Esnault-Pelterie’s original R.E.P. 1 aircraft and its engine preserved in the Musée national des Arts et Métiers. (PHGCOM image via Wikimedia Commons)

Sources:

– “Moteur Extra-Léger a Explosion” by Robert Esnault-Pelterie, Mémoires et Compte Rendu des Travaux de la Société des ingénieurs civils de France Bulletin (December 1907)

– Les aéroplanes et moteurs R.E.P. by Gérard Hartmann (4 MB pdf)

– Les Moteurs a Pistons Aeronautiques Francais Tome I by Alfred Bodemer and Robert Laugier (1987)

– “The First Paris Aeronautical Salon: Engines for Aeroplanes” Flight (16 and 23 January 1909)

– Aero Engines by G. A. Burls (1916)

– http://aviatechno.net/bib/001n_les_moteurs_aviation.php

– http://www.nmspacemuseum.org/halloffame/detail.php?id=7

– http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vickers_R.E.P._Type_Monoplane