By William Pearce

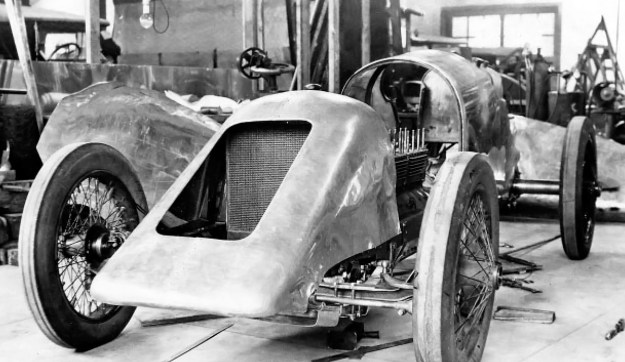

As World War II started to gain momentum and become a global conflict, Australia realized that it was in a precarious position. In the war’s early years, Australia did not have an industry devoted to building war material, and the ability of other nations to supply war machines to Australia was in doubt. Australia realized that they would need to develop their own war equipment. In November 1940, Australia began developing its own tank, the Australian Cruiser Tank Mark I (AC1).

The “clover leaf” Cadillac drive system of the Australian Cruiser Tank Mark I. The rear engine (top of image) is not visible, but its long drive shaft can be seen passing between the other two engines. All three drive shafts connect to the transfer box (bottom of image).

The AC1 Sentinel was based on the United States M3 medium tank, but selecting a power plant for the AC1 proved to be a challenge. The M3 was powered by a 400 hp (298 kW) Wright R-975 radial engine, built under license by Continental Motors. But a continuous supply of R-975 engines, Guiberson diesel engines, or any powerful engines could not be assured to Australia. A solution was found in the unlikely form of a Cadillac V-8 engine originally used to power various coupes and sedans. The Australians referred to the engine as the Cadillac 75 because of its use in the Cadillac Series 75 sedan, but it was also used in the Series 70 and various Series 60 automobiles.

The Cadillac 75 engine had made its debut in 1936. It was a flat head (side valve) engine with the intake and exhaust valves located on the Vee side of the cylinder. The engine was a monobloc design with cylinder banks cast integral with the crankcase. The V-8 also incorporated hydraulic valve lifters for durability. The engine was designed to be built more economically than Cadillac’s V-12 and other V-8 engines. The Cadillac 75 engine had a 3.5 in (89 mm) bore, a 4.5 in (114 mm) stroke, and a displacement of 346 cu in (5.7 L). It produced 135 hp (101 kW) and weighed around 890 lb (404 kg).

The Australian Cruiser Tank Mark III (AC3) powered by the Perrier-Cadillac 41-75 engine. Only one AC3 was fully assembled, and that tank is currently preserved at the Australian War Memorial in Campbell, Australia. (Australian War Memorial image)

The Cadillac 75 engine was readily available for import to Australia, but its 135 hp (101 kW) output was insufficient to power the 28 ton (25.4 metric ton) AC1 tank. As a result, AC1 designers, Colonel W. D. Watson and A. R. Code, decided to use three engines to power the tank. Watson was a British tank engineer on loan to Australia, and Code was the Director of Australia’s Armored Fighting Vehicle Production. The three-engine power package developed for the AC1 tank became known as a clover leaf arrangement and was built by General Motors’ Holden subsidiary in Melbourne.

In the clover leaf configuration, engine “3” was situated toward the rear of the tank, and engines “1” and “2” were located amidships, side-by-side. The engines were completely independent of one another, each having its own radiator and drive shaft. However, engine “3” also drove the cooling fan from six pulleys mounted on its driveshaft. The drive shafts for all three engines extended forward to a common transfer box near the middle of the tank. From the transfer box ran the final output shaft that connected to the tank’s gearbox. The AC1 tank could be run on two or even one of the Cadillac 75 engines.

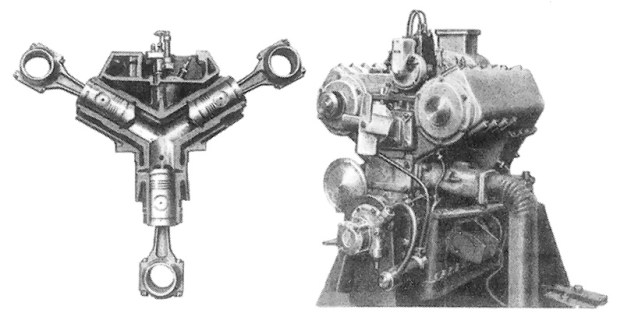

Front view of the Perrier-Cadillac 41-75 engine illustrates the odd cylinder bank arrangement. Note the single output shaft and how each exhaust manifold collects exhaust from three cylinder banks. A water pump and generator are driven from a belt at the front of each engine section.

The clover leaf Cadillac power package produced 330 hp (246 kW) at 3,050 rpm and was somewhat successful, powering 65 AC1 tanks. However, the rear engine did experience occasional cooling issues as a result of unequal coolant flow. The clover leaf’s three drive shafts, remote transfer box, and separate cooling systems added weight and complexity. As the Australian Cruiser Tank Mark III (AC3) was being designed in 1941, engineer Robert Perrier sought to simplify the clover leaf Cadillac power package. Perrier, a Frenchman, had been sent to Japan by the French government in 1940 and had subsequently made his way to Australia as Japan entered the war.

The AC3 Thunderbolt was an improved AC1 with better armor protection and firepower. To increase the performance of the three Cadillac 75 engines, Perrier mounted them radially to a common crankcase made from steel plates welded together. One engine was mounted on top of the crankcase, and the other two were mounted about 60 degrees to the left and right of the top engine. This configuration resulted in a rather odd looking engine, with its lower cylinder banks some 210 degrees apart. The engine was known as the Perrier-Cadillac 41-75; it was a lighter, more compact power package than the clover leaf configuration.

Rear view of the triangular, welded-steel crankcase of the Perrier-Cadillac engine. The power from all three engine sections was combined at the rear of the engine, and a single output shaft passed though the large, circular openings in the crankcase.

The Perrier-Cadillac engine had a single cooling system with one radiator, but each engine section had its own water pump. The remaining engine accessories were separate and operated independently of one another. At the rear of the Perrier-Cadillac engine, the crankshaft of each engine section was coupled to a common combining gear. The individual engine sections could be decoupled from the combining gear. A drive shaft extended from the combining gear at the rear of the engine, through the crankcase, and out the front of the engine.

The single output shaft of the Perrier-Cadillac engine allowed the transfer box used in the AC1 tank to be omitted, saving space and weight. The single output shaft also decreased mechanical losses, enabling the Perrier-Cadillac to produce more power than the clover leaf package with its three-into-one transfer drive arrangement. The 24-cylinder Perrier-Cadillac 41-75 displaced 1,039 cu in (17.0 L) and produced 397 hp (296 kW). The engine weighed around 3,000 lb (1,360 kg).

Rear view of the 397 hp (296 kW) Perrier-Cadillac engine. Behind the cover at the center of the engine is where the individual engine sections are connected to the single output shaft.

While the Perrier-Cadillac engine worked well, it did not go into production. A number of AC3 tanks were being built, but only one of these was fully assembled. The further improved Australian Cruiser Tank Mark IV (AC4) design followed, and it also used the Perrier-Cadillac engine. By 1943, the supply of war equipment to Australia had not been greatly impacted by the war, and equipment was imported faster than it could be domestically built. Australian resources were better utilized on projects other than tanks, and the Australian Cruiser tank programs were cancelled. However, the imported tanks did not completely match the Australian Cruiser tank design requirements, nor did they eclipse the Australian Cruiser tanks’ performance.

As a side note, the Perrier-Cadillac 41-75 was not the only engine intended to power AC4. A new engine was under development; it was comprised of four air-cooled, four-cylinder de Havilland Gypsy Major engines mounted in an H configuration on a common crankcase. Starting in 1941, Gypsy Major engines were produced under license at General Motors’ Holden plant. With its 4.65 in (118 mm) bore and 5.51 in (140 mm) stroke, the Quad-Gypsy engine would have displaced 1,495 cu in (24.5 L) and produced 510 hp (380 kW) at 2,500 rpm. The 16-cylinder engine weighed around 1,500 lb (680 kg). The Quad-Gypsy engine was domestically-built, simpler, more powerful, and much lighter than the Perrier-Cadillac engine.

The 16-cylinder, QuadGipsy engine would provide around 510 hp (380 kW) for the Australian Cruiser Tank Mark IV. Lighter and more powerful that the Perrier-Cadillac, the engine would have been built in Australia by General Motors-Holden. Concealed in the shroud around the output shaft was a fan to force air through the cylinders’ cooling fins. Various accessories were mounted on top the engine.

While similar engine concepts, no direct relation has been found between the Perrier-Cadillac and the Chrysler A57 Multibank.

Sources:

– Tanks Australian Cruiser Mark-1 Instruction Book (1943)

– Australian Sentinel and Matildas (AFV Weapons 31) by Major James Bingham

– The Role of Science and Industry (Australia in the war of 1939-1945) by D.P. Mellor (1958)

– http://www.mheaust.com.au/Aust/Research/Sentinel/sentinelmk.htm

– http://www.secretprojects.co.uk/forum/index.php/topic,8514.0/all.html

– http://forum.worldoftanks.com/index.php?/topic/490738-inside-the-chieftains-hatch-ac-1-sentinel/