By William Pearce

The first original engine made by the Fairey Aviation Company (FAC) was the P.12 Prince. Designed by Captain Archibald Graham Forsyth, the Prince was a 1,559 cu in (25.5 L) V-12 that was ultimately rated at 750 hp (559 kW) for normal output and 900 hp (671 kW) for maximum output.

The Fairey P.24 Monarch was a final attempt by Fairey Aviation to produce a piston aircraft engine. The engine proved to be reliable and had some unusual features, but nothing about it was revolutionary. Both Britain and the United States passed at the opportunity to produce the engine.

Seeking more power, Forsyth investigated a 16-cylinder engine designated P.16 that displaced 2,078 cu in (34.1 L). A V-16 design was initially considered, but the configuration was changed over concerns regarding the engine’s length combined with excessive torsional vibrations and stress of the long crankshaft. The P.16 configuration was switched to an H-16 with four banks of four cylinders. However, by switching to an H-24 configuration with four banks of six cylinders, a more powerful engine could be developed that would possess the same frontal area as the H-16. In fact, there is little evidence from primary sources that indicates a P.16 engine or an H-16 configuration were ever seriously considered. Design work on the H-24 engine had begun by October 1935. The H-24 engine was designated P.24 and may have been initially named “Prince” (like the P.12). For a time, the P.24 was called “Queen,” but the name was later changed to “Monarch.”

The Fairey P.24 Monarch was a vertical H engine in which the left and right 12-cylinder engine sections could be operated independently of each other. The aluminum crankcase was made of an upper and lower half. Each bank of six cylinders was mounted to the crankcase. An aluminum cylinder head attached to the cylinder bank. The P.24 retained the bore and stroke of the P.12 (and P.16) engine. Each cylinder had two intake valves and one exhaust valve, all actuated by a single overhead camshaft driven from the rear of the engine. The 1.8125 in (46 mm) diameter intake valves were operated by a T-type tappet, and the 2.25 in (57 mm) diameter exhaust valve was operated directly by the camshaft. It is interesting to note that various British patents (no. 463,501 and 465,540) filed by FAC and Forsyth show four valves per cylinder. No information has been found of a four-valve head being fitted to a P.24 engine.

Drawings taken from British patent 463,501 illustrate the integral passageways of the P.24’s induction system. The drawn configuration was nearly identical to that used on the actual engine. The sectional view on the right illustrates the numerous sharp turns the air/fuel mixture made on its way into the cylinders.

Mounted to each side of the engine was a single-stage, two-speed supercharger with two carburetors mounted on its inlet. The superchargers were driven from the rear of the engine at 8.3475 times crankshaft speed through three step-up gears. Via a short manifold, each supercharger delivered air into passageways cast integral with the crankcase, cylinder bank, and cylinder head. A single passageway brought air into two cylinders. It was noted in British patent 463,501 that having intake passageways cast integral with the crankcase made the engine cleaner, more rigid, and opened the vertical space between the cylinder banks for either an oil cooler or gun. However, if a gun were to be considered, the crankcase construction did not allow it to fire through the propeller hub. Rather, the gun would need to be synchronized to fire through the propellers.

The air/fuel mixture was ignited by two spark plugs—one on each side of the cylinder. The spark plugs were fired by four magnetos mounted to the rear of the engine. The upper two magnetos fired the spark plugs located on the inner side of the cylinders, and the lower two magnetos fired the spark plugs located on the outer side of the cylinders. The left and right sides of the P.24 had the same firing order: 1U, 5L, 4U, 1L, 2U, 4L, 6U, 2L, 3U, 6L, 5U, and 3L. The first and last cylinders had their own exhaust stack, but the middle four cylinders were paired off with a shared exhaust stack. This arrangement gave the P.24 16 exhaust stacks, which often caused the engine to be mistaken for an H-16.

Another drawing from British patent 463,501 details the induction, valves, and exhaust. Although the drawing has two exhaust valves per cylinder, the P.24 as built had only one exhaust valve. Note that each bank of six cylinders only has four exhaust stacks. This gave a total of 16 stacks for the P.24 engine, which is why it is occasionally mistaken for an H-16.

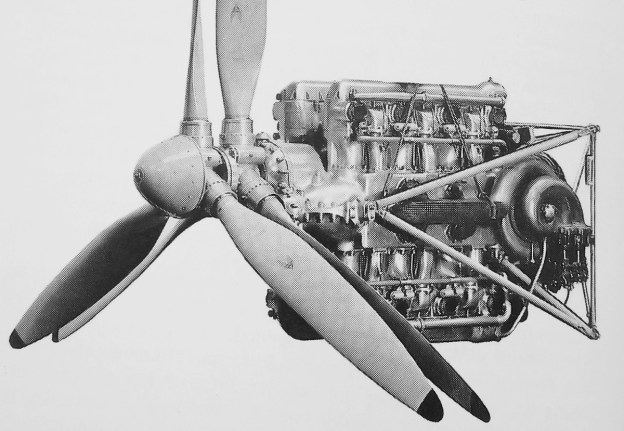

At the front of the engine, each crankshaft was geared to a separate propeller shaft at a .5435 reduction. The two propeller shafts made up a coaxial, contra-rotating unit. The crankshafts and accessories for each engine section rotated in opposite directions. When viewed from the rear, the left crankshaft rotated clockwise and powered the front propeller. The right crankshaft rotated counterclockwise and powered the rear propeller. The P.24’s fully-adjustable, contra-rotating propeller was developed by FAC. Each crankshaft had six throws and was supported by eight main bearings. The pistons were connected to the crankshaft by fork-and-blade connecting rods, with the fork rod servicing the lower cylinders and the blade rod servicing the upper cylinders. Since they rotated in opposite directions, the crankshafts and engine accessories were not interchangeable.

When either the left or right side of the engine was shut down, the other side of the engine would continue to operate and power its propeller. This gave any aircraft powered by a P.24 engine the reliability of two engines without the drawback of asymmetrical thrust in an engine-out situation. This configuration also allowed half of the engine to be shut down to extend the aircraft’s range or loiter time. Although the cooling and oil systems of the engine sections were separate, they used common tanks and coolers during engine tests. It was noted that completely separate coolers and tanks could be installed in an aircraft to make the engine sections truly independent of one another.

The P.24 installation drawing illustrates the H-24 engine as built. British patent 463,501 mentioned the possibility of installing a gun between the upper cylinder banks, but no provisions for such equipment were incorporated into the actual engine.

The Fairey P.24 Monarch had a 5.25 in (133 mm) bore, a 6.0 in (152 mm) stroke, and a compression ratio of 6 to 1. The engine displaced 3,117 cu in (51.1 L) and was originally rated for 2,000 hp (1,491 kW) at 2,600 rpm. However, Forsyth felt the engine could be developed to 2,600 hp (1,939 kW) at 3,000 rpm. The two-speed superchargers gave critical altitudes of 6,000 and 13,000 ft (1,829 and 3,962 m). Fuel consumption was .63 lb/hp/hr (383 g/kW/h) at takeoff, .55 lb/hp/hr (335 g/kW/h) at full power, and .45 lb/hp/hr (274 g/kW/h) at 60% throttle. The P.24 engine was 86.25 in (2.19 m) long, 43.0 in (1.09 m) wide, and 52.5 in (1.33 m) tall. The engine weighed around 2,330 lb (1,057 kg), although 2,180 lb (989 kg) is given by many sources. Perhaps the discrepancy in reported weight is a result of the engine’s weight changing with the installation of various accessories.

The P.24 was first run in 1938. The test cell at FAC was not built for the full power of the P.24, so just half of the engine was run at a time. By 6 October 1938, the engine was successfully completing two-hour runs without issues. Arrangements were made to install the P.24 in a Fairey Battle light bomber, and the engine was being considered for use in the Hawker Tornado fighter. The P.24 started its 50-hour civil type test on 13 May 1939 and successfully completed the test on 14 June 1939. For the test, the engine ratings were a normal output of 1,200 hp (895 kW) at 10,500 ft (3,200 m) and 2,400 rpm, and a maximum output of 1,450 hp (1,081 kW) at 10,500 ft (3,200 m) and 2,750 rpm. It appears that a single-speed supercharger delivering just .5 psi (.04 bar) of boost was used for the 50-hour test.

This side view of the P.24 engine installed in Fairey Battle K9370 illustrates the very large radiator installed under the aircraft. It is easy to understand why the engine, with its 16 prominent exhaust stacks, is often thought to be an H-16. Note that the propellers do not have a complete spinner, which was installed later.

The P.24-powered Battle (K9370) first flew on 30 June 1939, piloted by Christopher S. Staniland. A short time later, a P.24 test engine achieved 1,540 hp (1,148 kW) at 2,600 rpm with 3 psi (.21 bar) of boost for takeoff. With P.24 tests moving forward, FAC looked to apply the engine to new aircraft designs. On 19 October 1939, FAC proposed using the P.24 engine in aircraft designed to specifications N8/39 and N9/39. Designed by FAC chief designer Marcel Lobelle, the same basic single-engine, two-seat fighter design was used to satisfy both specifications, with the addition of a turret for N9/39. In Lobelle’s drawings, the FAC engine was labeled as the “Queen,” but it was visually identical to the P.24 as built. In addition, the late-1939 time frame was after FAC had moved away from 16-cylinder engine designs. In the late-1939 proposals, the engine was rated at 1,320 hp (984 kW) for takeoff and 1,170 hp (872 kW) at 15,000 ft (4,572 m).

During 1940, a number of short runs were made up to 1,750 hp (1,305 kW), but there were no long periods of running at these high outputs. Trouble was experienced with the superchargers and main bearings. A maximum of 2,200 hp (1,641 kW) was achieved, but not with both halves of the engine running at the same time. Each individual engine half achieved an output of 1,100 hp (820 kW), adding up to the 2,200 hp (1,641 kW) figure. In fact, each engine half made two runs at 1,100 hp (820 kW), but the runs were only a short duration of two minutes each.

A well circulated image of the P.24-powered Battle in Britain. Taken at the same time is another image that shows the front propeller turning (left side of the engine running). A doctored set of these images had the exhaust stacks removed to keep the engine’s configuration a secret. Note the complete spinner.

In October 1940, the Air Ministry made it clear that no production orders for the P.24 engine would be placed. Instead, the focus was on other engines already further developed and being designed by established engine manufacturers with greater facilities for production. In April 1941, the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) expressed some interest in the P.24. Since the P.24 had twin-engine reliability, and its contra-rotating propellers eliminated torque reaction, the engine was ideally suited for carrier operations. However, the Air Ministry again asserted that there would be no production of the engine. This did not stop FAC from continuing to push the P.24 engine, even proposing in mid-1942 that the Fairey Firefly carrier fighter should be re-engined with a P.24 that would produce 2,150 hp (1,603 kW) at 3,000 rpm. The Air Ministry was not interested, and the plan went no further. The P.24-powered Battle was turned over to Royal Aircraft Establishment Farnborough on 12 July 1941. By this time, P.24 engines on test had been run 20 hours at 2,000–2,100 hp (1,491–1,566 kW) and five hours at 2,100–2,300 hp (1,566–1,715 kW).

Fairey had discussed the P.24 engine with United States Army Air Force (AAF) officials in June 1941. The following month, Forsyth visited the US to give more details about the engine. Fairey and Forsyth felt that the Air Ministry had made a mistake in exclusively backing the Napier Sabre and not providing any support for the P.24. They wanted P.24 development and production to continue in the US; production in the US by an established engine manufacturer would be easier than FAC undertaking the task themselves. By this time, the name “Monarch” was applied to the P.24 engine. In August 1941, the AAF stated that they were not interested in the development or production of the P.24 engine, but they were interested the in the contra-rotating propellers developed for the engine. However, Fairey stated in a letter dated November 1941 that Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio had prepared three-view drawings of the P.24 installed in the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter and the Curtiss A-25 Shrike (SB2C Helldiver) dive bomber. Fairey also stated that the Ford Motor Company was engaged in discussions about producing the engine.

Uncowled view of the P.24 engine installed in the Battle. Note the supercharger, intake manifold, and front engine mount.

The apparent reversal of the AAF’s interest in P.24 production seems odd, and it may have been more optimism on Fairey’s part than what was really expressed by the AAF. Fairey did want to get the engine to the US, and claiming that the AAF was interested was the quickest way to get the cooperation of the Air Ministry, who had been battling Fairey for quite some time. Regardless of the AAF’s level of interest in the engine, they were certainly interested in the contra-rotating propellers. The P.24-powered Battle was shipped to the US on 5 December 1941. Another P.24 engine was delivered to Farnborough for further testing, and a third Monarch engine was prepared for shipping to the US. With the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the second P.24 engine was never sent to the US.

Many sources state that the P.24 engine was considered to replace the Pratt & Whitney R-2800 in the P-47. It should be noted that an order for 773 P-47Bs (602 were finished as P-47Cs) was placed in September 1940; the XP-47B made its first flight on 6 May 1941, and an order for 805 P-47Ds was placed in October 1941. All of this P-47 activity occurred before the AAF touched the P.24 engine and before the US entered World War II. An additional 1,050 P-47Ds and 354 P-47Gs were ordered in January 1942, before the AAF had much, if any, time to evaluate the P.24 engine. It would seem that the AAF was quite content with the R-2800 engine, since full-scale P-47 production was underway, and 2,982 aircraft were on order. A request from Fairey dated January 1943 sought a new set of propellers for a P.24 engine installed in a P-47. At the time, the P-47 was two months away from entering combat, with hundreds of aircraft produced and thousands on order. It seems highly unlikely that any engine change would have been seriously considered by the AAF.

The P.24 was flown extensively in the US, but the AAF was mostly interested in the contra-rotating propeller. The Battle retained its serial number, but the British roundels were painted over, and US markings were applied. Note the star under the wing and the stripes on the tail. Some contend the Battle was designed to be powered by the P.24. However, the Battle’s origin can be traced to 1933, and the P.24’s design was initiated over two years later, in 1935. An early design of the Battle was powered by the Fairey P.12 Prince.

When the AAF received the P.24-powered Battle at Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio, it had around 87 hours of flight time. The P.24 engine had a takeoff rating of 2,100 hp (1,566 kW) and military ratings of 2,100 hp (1,566 kW) at 6,000 ft (1,829 m) and 1,850 hp (1,380 kW) at 13,000 ft (3,962 m); all ratings were at 3,000 rpm with 9 psi (.62 bar) of boost and using 87 octane fuel. Forsyth believed the engine was capable of 2,600 hp (1,939 kW) with 100 octane fuel. The AAF found the coaxial propellers and the “double engine” concept novel, but found the rest of the engine conventional. The AAF felt the design of the P.24 limited its further development. Since the intake manifolds were cast into the engine’s crankcase, a complete redesign would need to be undertaken to improve their flow. As it was, the intake manifolds fed the air/fuel mixture clumsily into the cylinders through five turns, some of which were fairly sharp 90-degree bends. The integrally cast manifold also caused the air/fuel mixture to be heated as it flowed to the cylinders. Another issue was that the gear reduction housing was cast integral with the crankcase. If a failure caused damage to the gear reduction housing, the entire crankcase would need to be scrapped. With all of the integral components, the two crankcase castings were large and complex. The AAF also noted the non-interchangeability of the crankshafts and other components. The AAF remarked that BMEP (brake mean effective pressure) achieved by the P.24 at 3,000 rpm with 9 psi (.62 bar) of boost was matched by the Allison V-3420 with 3.75 psi (.26 bar) of boost at the same rpm. In addition, the relatively low critical altitude of the P.24 meant the Rolls-Royce Merlin 60 series had a 160 hp (119 kW) advantage at 30,000 ft (9,144 m).

The sole surviving P.24 Monarch engine and its propellers are preserved and housed in the Fleet Air Arm Museum at Yeovilton. Only around three P.24 engines were built. (Rory57 image via flickr.com)

Of course, enhancements to the P.24 could be made, and Forsyth suggested that further development of the engine be conducted in the US. This included increasing the bore of the P.24 to 5.5 in (140 mm), which would give a displacement of 3,421 cu in (56.1 L) and an output of 3,000 hp (2,237 kW). In addition, a P.32 could be built with four banks of eight cylinders for a total displacement of 4,156 cu in (68.1 L). The bore of the 32-cylinder P.32 could also be increased to 5.5 in (140 mm) for a total displacement of 4,562 cu in (74.8 L). A 24-cylinder engine with a 6.0 in (152 mm) bore and stroke could be developed that would displace 4,072 cu in (66.7 L) and produce 3,400 hp (2,535 kW).

Additions to the basic P.24 included developing a two-stage supercharger that would enable the engine to produce around 1,800 hp (1,342 kW) at 36,000 ft (10,973 m). The AAF mentioned that the stages would be separate, with one stage driven from the propeller gear reduction at the front of the engine. In May 1942, Forsyth applied for a US patent (no. 2,470,155) that addressed some of the AAF’s concerns regarding the engine’s gear reduction and supercharger. The patent outlines the basic P.24 engine but with a detachable propeller gear reduction. The engine could be used in a variety of aircraft, and different gear reductions would be fitted to provide the desired propeller rpm based on the aircraft’s role. An extension could be installed between the engine and propeller gear reduction that had a mounting to drive an additional supercharger on each side of the engine. In addition, different superchargers with their own gearing could be installed on the engine to provide different levels of boost based on the needs of the aircraft. In some configurations, superchargers could be engaged as the aircraft gained altitude. In addition, US patent 2,470,155 described how P.24 engines could be coupled to create an H-48 engine. A 48-cylinder engine would displace 6,234 cu in (102 L) and produce over 4,400 hp (3,281 kW).

In June 1942, FAC and Forsyth applied for another US patent (no. 2,395,262) that detailed another supercharger configuration, but with a turbosupercharger mounted to the front of the engine. This configuration was briefly mentioned in US patent 2,470,155. In US patent 2,395,262, the turbosupercharger was the first stage and was powered by the exhaust gases from the top row of cylinders. Exhaust from the lower cylinders was combined with the exhaust from the turbosupercharger. The pressurized air flowed from the turbosupercharger to the gear-driven supercharger at the rear of the engine. The air was pressurized further and directed into the engine via manifolds as seen on the P.24.

Forsyth envisioned adding turbosuperchargers to the P.24 as another stage of charging. This concept is outlined in British patent 463,984 (top, granted in 1937) and US patent 2,395,262 (bottom, granted 1946). In addition, a front mounted supercharger driven from the propeller gear reduction was contemplated. All of these arrangements were to give the P.24 better high-altitude performance, but none were built.

Forsyth had been considering the combined turbo and supercharger arrangement since before the P.24 first ran. This concept was outlined in a British patent (no. 463,984) applied for in 1935 and granted in 1937. In this patent, the turbosuperchargers would be mounted on the sides of the engine, outside of the induction manifolds. The gear-driven supercharger would be run alone for low altitude operation, and the turbosupercharger would provide additional boost at higher altitudes. At a certain altitude, valves would open, allowing engine exhaust into the turbosupercharger to start its operation. At the same time, valves on the gear-driven supercharger’s inlet pipes would close. The turbosupercharger would become the first stage of charging and feed air into the gear-driven supercharger, in which fuel would be added and the mixture further pressurized before being fed into the cylinders.

Forsyth also suggested developing a jet engine section to be added to the P.24. British patent 591,048 described the P.24 employed in a semi-motorjet configuration. Behind the piston engine was a supercharger, and behind the supercharger was a large, engine-driven compressor. Fuel was injected and ignited in the compressor to generate thrust. Three different power options were available: the engine could drive the propellers only; the engine could drive both the propellers and the compressor; or the propellers could be disengaged, and the engine would drive the compressor alone, the compressor generating the thrust needed to maintain flight. A series of clutches connected or disconnected the propellers, piston engine, and compressor.

As the jet age dawned, Forsyth looked to incorporate the new technology into the P.24. The top drawing is from British patent 591,048 and describes a single compressor (H) mounted behind the engine (A) and supercharger (F). Induction pipes (34) lead from the supercharger to the engine. The bottom drawing is from British patent 591,189 and describes a compressor (M) mounted behind each engine section. Both configurations allow the engine to drive the propellers, the compressor, or both. In addition, fuel could be injected and ignited into combustion chambers (I top and S bottom) for additional thrust. The patents were applied for in 1944 and granted in 1947.

British patent 591,189 described a very similar engine concept as the semi-motorjet listed above; however, two compressors were used. Each engine section had its own compressor section, and the piston engine’s superchargers were again located on the side of the engine. In addition to the power options listed in the previously mentioned patent, one engine section could drive one propeller, while the other engine section could drive one compressor. Both of the patents that incorporated compressors with the P.24 engine were applied for in 1944 and granted in 1947.

Forsyth even thought about using P.24 components to create a marine engine. US patent 2,389,663 outlines P.24 cylinder banks being used in a U-12 configuration. Two U-12 engine sections would be combined to create a U-24 engine. The drive for the contra-rotating marine propellers would come from between the two U-12 engine sections. The patent notes that the six-cylinder engine sections could be run independently and that the superchargers could be engaged or disengaged. Low-speed operation would consist of running one six-cylinder engine section without supercharging. High-speed operation would employ all 24 cylinders and four superchargers.

For marine use, Forsyth mounted the four banks of the P.24 on a new crankcase to create a U-24 engine. This drawing from US patent 2,389,663 shows the engine and how it would drive a contra-rotating propeller. The bevel drive to the supercharger is shown by number 10.

All of these inventive propulsive ideas came to naught. As previously mentioned, the British supported the Sabre and not the P.24. The AAF felt that only 2,460 hp (1,834 kW) at 3,000 rpm would be obtained from the P.24 (as built) with 100 octane fuel and that no part of the engine was so remarkable that it warranted production in the US. This opinion did not stop the AAF from adding 250 hours of flight time to the P.24 before the Battle was returned to Britain in 1943. The aircraft logged around 340 hours powered by the P.24 engine.

Some suggest that if FAC had received the resources given to Napier for development of the Sabre, the P.24 would have been a phenomenal engine. The P.24 was a good engine, but its performance does not appear to be exceedingly remarkable for the era in which it was developed. While it is true that the P.24 performed reliably, the 3,117 cu in (51.1 L) engine was producing under 2,000 hp (1,491 kW) for most of its developmental life. A P.24 Monarch engine and its contra-rotating propellers survived and are currently on display in the Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm Museum at Yeovilton. The engine and propellers were most likely those used on the Battle.

A variety of P.24 engine configurations were illustrated in US patent 2,470,155. All of the different configurations are reminiscent of what Allison envisioned for the V-1710 and V-3420. Note the bevel gear drives for the power shafts.

Sources:

– Fairey Aircraft since 1915 by H. A. Taylor (1988)

– British Piston Aero-Engines and their Aircraft by Alec Lumsden (2003)

– World Encyclopedia of Aero Engines by Bill Gunston (2006)

– Fairey Firefly by W. Harrison (1992)

– Report on 50 Hours Civil Category Type Test Fairey P.24 – Series I (October 1939)

– Memorandum Report on Fairey P-24 (Monarch) Engine by B. Beaman, F. L. Prescott, E. A. Wolfe, and Opie Chenoweth (22 August 1941)

– Memorandum Report on Evaluation of P-24 Engine and Coaxial Rotating Propellers by Air Cops Material Division (27 August 1941)

– “Improvements in or relating to Gaseous Fuel Induction Pipes for Internal Combustion Engine” British patent 463,501 by Fairey Aviation Company and Archibald Graham Forsyth (granted 1 April 1937)

– “Improvements in or relating to Supercharging Internal Combustion Engines” British patent 463,984 by Fairey Aviation Company and Archibald Graham Forsyth (granted 9 April 1937)

– “Improvements in or relating to Valve Mechanism for Internal Combustion Engines” British patent 465,540 by Fairey Aviation Company and Archibald Graham Forsyth (granted 10 May 1937)

– “Improvements in or relating to Power Plants for Aircraft” British patent 469,615 by Fairey Aviation Company and Archibald Graham Forsyth (granted 29 July 1937)

– “Marine Power Unit” US patent 2,389,663 by Archibald Graham Forsyth (granted 27 November 1945)

– “Supercharging Arrangement” US patent 2,395,262 by Archibald Graham Forsyth (granted 19 February 1946)

– “A Power Unit for Aircraft and the like” British patent 591,048 by Fairey Aviation Company and Archibald Graham Forsyth (granted 5 August 1947)

– “Improvements in or relating to Power Units” British patent 591,189 by Fairey Aviation Company and Archibald Graham Forsyth (granted 11 August 1947)

– “Supercharged Multiple Motor Internal-Combustion Unit for Aircraft” US patent 2,448,789 by Archibald Graham Forsyth (granted 7 September 1948)

– “Power Plant Assembly” US patent 2,470,155 by Archibald Graham Forsyth (granted 17 May 1949)

– http://ww2aircraft.net/forum/threads/fairey-aero-engines-any-good-info.30710/

Thank you for all your work putting this wonderful website together.

Thank you for your kind words.

Lot’s of scope for a very long barreled high velocity 20mm gun firing through the bottom cylinder trough of the example fitted to the Battle. Have the gubbins pass under the pilot and the rear gunner reload the drums. Would have given the plane the offensive punch against ground units it needed to be a truly successful ground attacker.

Perhaps. There were some accessories and piping between the lower banks, but there was certainly more room than between the upper banks.

So the integral manifolds were past practice as exemplified by the P12. Which seemed to have included low boost or normally aspirated. Such a pity FAC didn’t figure out the times had changed. All that effort to make an integrated engine and that integration was a factor in it’s failure. thank you for another great write up. Why oh why was the Sabre the only successful twin crank aircraft engine? Is that a fair question?

Glad you liked the article. I think the AAF was not interested in the engine and noted the integral intake passageways as a problem if further engine development was to occur. I don’t think the AAF passed on the engine solely due to the induction system. Other engines, like the Sabre, also had integral intake passageways. I don’t think the P.24 was a bad engine—some, like Rod Banks, favored it over the Sabre. But the Sabre was backed by George Bulman and the Ministry of Aircraft Production, and I don’t think Fairey was ever given much support for engine development. Other twin-crank engines were not exactly failures; the Rapier, Dagger, V-3420, DB 606 and DB 610 all achieved some level of success, but none may have benefited from the governmental and financial backing that the Sabre did. The Rapier and Dagger overheated on the ground. The V-3420 never seemed to find a purpose, and the DB 606 and 610 seemed to have been doomed by their installation in the He 177. However, they all seemed to run just fine in certain applications. I may be wrong, but I think the Sabre (and R-3350) had a much more inglorious introduction after production began that the other engines listed (not that many of the others were produced, or that the DB’s service was good). I think the Sabre’s success was based on the fact that it had a viable application and the Air Ministry continued to support it through a desperate time.

Hi Bill,

Thanks for the well-researched & written article on this ‘odd ball’ engine.

The US Air Materiel Division report does a cogent job of parsing the claims by Fairey designer Mr Forsyth against factual analysis – which tends to derate them significantly, based on an educated appraisal of its actual architecture & functional characteristics – including a list of “…objectional features”… in its “…basic design”… that “…require considerable redesign rather than further development only.”

The Napier Sabre was robustly designed by Halford et al, (unlike the Fairey unit), it was the rush to service introduction – as per the Wright R-3350, as you duly note, for which the production engineering likewise was problematic – & initially caused angst for real reasons, yet both engines did respond to systematic de-bugging, & did go on – to provide good service in wartime/post-war.

Ta,

James.