By William Pearce

In 1936, Siegfried and Walter Günter began design work on the Heinkel He 119, an experimental, unarmed, high-speed light bomber and reconnaissance aircraft. The engine for the He 119 was buried in the fuselage, and the Günter brothers quickly realized that no engine available was capable of providing the desired power in excess of 2,300 hp (1,691 kW). Heinkel requested proposals from Germany’s leading aircraft engine manufacturers. Daimler-Benz responded with a plan to construct a doppelmotor (double engine) by coupling two DB 601 V-12 engines to create the 24-cylinder DB 606. Combining two engines as a single unit was seen as a quick way to double engine power without spending years to develop a new powerplant.

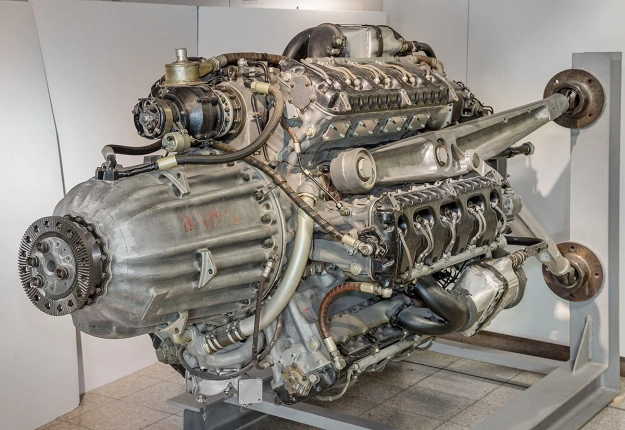

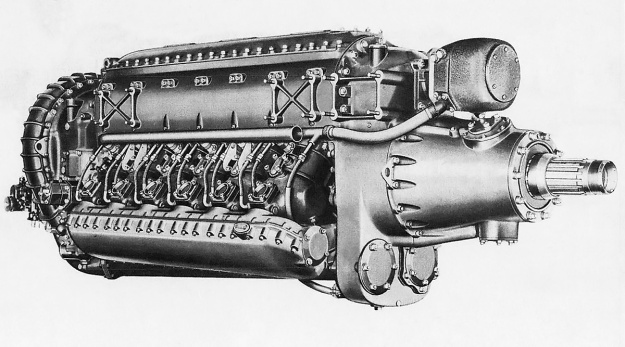

The Daimler-Benz doppelmotoren (double engines) were quite literally formed by combining two separate engines. The DB 606 was made from two DB 601 engines. The levers attached to the combining gear reduction housing controlled the coupling and decoupling of the separate engine sections.

Development of the DB 601 was started in the mid-1930s and based on the DB 600. The main differences between the engines were that the DB 600 used a carburetor and geared supercharger, whereas the DB 601 used fuel injection and a variable speed supercharger. The DB 601 was an inverted, liquid-cooled engine with two banks of six cylinders. Its single-piece Silumin-Gamma (aluminum alloy) crankcase was closed out by a cover affixed to its top side. The six-throw crankshaft was supported by seven main bearings, and each main bearing was secured by four bolts and one transverse bolt that passed through the crankcase. The crankshaft turned counterclockwise. Fork-and-blade connecting rods were used, with the forked rods serving cylinders on the right side of the engine (when viewed from the rear). The connecting rods ran on roller bearings, but the blade rod had an additional plain bearing between it and the roller bearing.

The two cylinder blocks were made from Silumin (aluminum-silicon alloy) and attached to the bottom of the crankcase at a 60 degree angle. Each cylinder block consisted of six cylinders with integral cylinder heads. The dry cylinder liners (barrels) were made of chrome steel and were screwed and shrunk into the upper cylinder block. Threaded liner skirts protruded into the crankcase toward the crankshaft. A locking ring screwed onto each liner skirt and drew and secured the entire cylinder block to the crankcase. The locking ring had “teeth” around its outer edge and was tightened by a special pinion tool that was held secure in the crankcase and rotated the ring.

Each cylinder had two spark plugs mounted on its outer side and a fuel injector mounted on its inner side. The Bosch fuel injection pumps were mounted in the Vee between the cylinder banks. Two intake valves on the inner side of the cylinder brought in air. The combustion gasses were expelled through two sodium-cooled exhaust valves on the outer side of the cylinder. All four valves per cylinder were actuated via rockers by a single overhead (technically underhead) camshaft, which was driven by a vertical shaft at the rear of the engine.

The DB 601’s propeller shaft was driven clockwise via spur gears through a gear reduction housing mounted to the front of the engine. The gear reduction was made so that a gun or cannon could be mounted behind the engine and fire through the Vee between the cylinder banks and out the propeller’s hub. Mounted to the rear of the engine was an accessory section that provided the drives for the magnetos, generator, starter, fuel and oil pumps, and the transversely mounted supercharger.

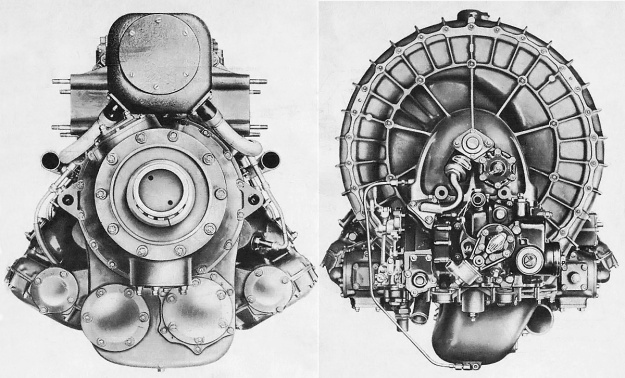

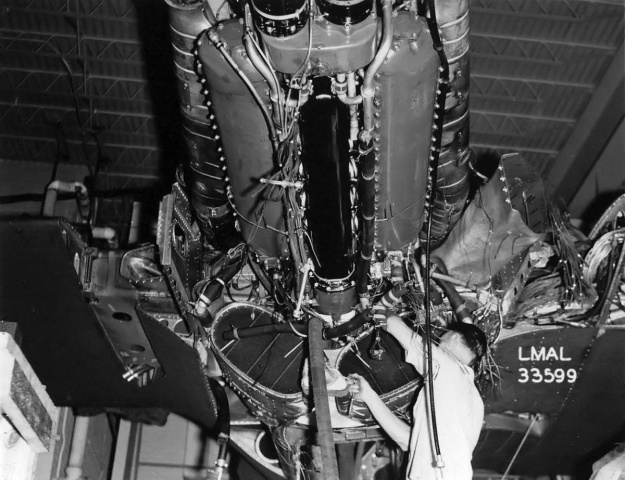

Bottom view of a DB 606 illustrates the separate engine sections. Note the rear engine mount which joined the two engine sections. The fuel injection pump for each engine section can be seen in the Vee between the cylinder banks.

The supercharger was mounted on the left side of the engine and driven from the crankshaft via a variable speed fluid coupling. In simple terms, two oil pumps supplied oil that flowed through the supercharger coupling. One pump continuously supplied the amount of oil needed for the supercharger to operate at its lowest (sea level) speed. The second pump was barometrically controlled and gradually supplied more oil as the aircraft’s altitude increased. At the engine’s critical altitude, the second pump was supplying the maximum amount of oil, and the supercharger was at its maximum speed. There was always some degree of slip in the coupling, but it was minimal (a few percent) at full speed. The variable speed of the supercharger created a gradual power curve rather than the saw-tooth power delivery of two- or three-speed superchargers. Air from the supercharger flowed through an intake manifold that looped in the Vee between the cylinder banks.

To form the DB 606, two DB 601 engines were mounted side-by-side at an included angle of 44 degrees and joined by a common propeller gear reduction. In this configuration, the engine banks formed an inverted W, and the inner cylinder banks were only eight degrees from vertical. The right and left engine sections were respectively referred to as the “W-Motor” (or DB 601 W) and the “X-Motor” (or DB 601 X). The exhaust ports for both inner cylinder banks were positioned in the narrow space between the two engine sections. DB 606 differed from the DB 601 by using the new propeller gear reduction and a modified accessory drive. The two engine sections drove a single propeller, and no gun or cannon could be fitted to fire through the propeller hub. Bolted between the two engine sections and near their rear was a mount for suspending the back of the DB 606 to the aircraft. The left and right engine sections remained separate with the exception of the gear reduction and the rear mount.

The new gear reduction housing combined the output from the two engine sections and fed it into a single propeller shaft, which typically had an extension that was approximately 44 in (1.11 m) long. The combining gear allowed the manual decoupling and recoupling of an engine section. Recoupling could only be accomplished when the engine sections were operating at the same RPM. In addition, an engine section would be automatically decoupled if its speed dropped suddenly compared to the other engine section. The coupling of each engine was accomplished by dogs (often referred to as claws in German literature) on a flange splined to the crankshaft that engaged dogs on a coupler that drove a spur gear in the reduction housing. To disengage an engine section, a lever for that engine section on the gear reduction housing had to be pulled forward. This would pull the coupler toward the propeller and disengage it from the crankshaft. The coupler would still be connected to the gears in the reduction housing. The levers on the engine were linked to levers in the cockpit, and the individual engine sections were started one at a time.

Different combining gear reductions enabled the propeller of the DB 606 to turn either clockwise or counterclockwise without changing the counterclockwise rotation of the engines’ crankshafts. The propeller of the DB 606 A turned clockwise. A 33-tooth gear on each of the two crankshafts meshed with an 80-tooth gear on the propeller shaft to create a .4125 reduction. The combining gear on the DB 606 B incorporated idler gears in the lower housing that enabled the propeller to turn counterclockwise. The idler gears increased the engine’s weight by approximately 88 lb (40 kg). For the DB 606 B, a 31-tooth gear on each of the two crankshafts meshed with 39-tooth idler gears, which engaged the 75-tooth gear on the propeller shaft to create a .4133 reduction. With two fewer gears, the combining gear reduction housing on the DB 606 A was initially smaller with angled corners when compared to that of the DB 606 B. However, to simplify production, later DB 606 A engines used the same larger, more rounded housing as the DB 606 B.

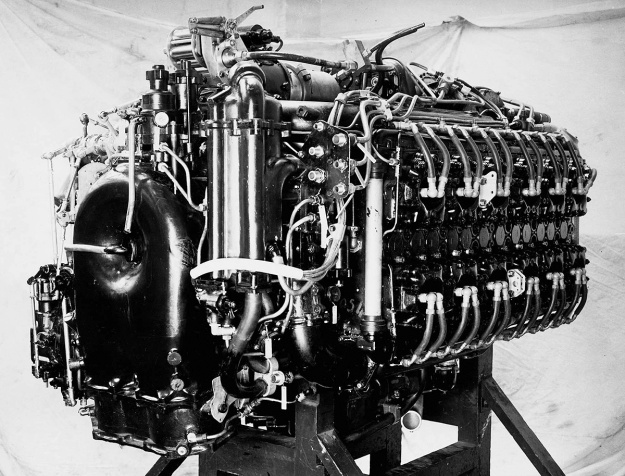

Rear view of a DB 606 displays the mirrored accessories on the back of each engine section. The left engine (X-Motor) had the standard accessory housing and supercharger. The accessory section of the right engine (W-Motor) was unique to the doppelmotor. The square mounting pad for the cannon can be seen at the center of each engine section, but this was not used on the doppelmotoren.

The supercharger and accessory section of the right DB 606 (W-Motor) engine section was basically the same as that used on the DB 601. The supercharger and accessory section of the left DB 606 (X-Motor) engine section was a mirror image of the left section so that the supercharger was on the right side of the engine.

The Daimler-Benz DB 606 A/B had a 5.91 in (150 mm) bore, a 6.30 in (160 mm) stroke, and a total displacement of 4,141 cu in (67.86 L). The engine was 6 ft 10 in (2.08 m) long without an extension shaft, 5 ft 4 in (1.63 m) wide, and 3 ft 6 in (1.06 m) tall. The dry weight of the DB 606 A was 3,263 lb (1,480 kg), and the dry weight of the DB 606 B was 3,373 lb (1,530 kg). Initially, 1,175 hp (864 kW) DB 601 Aa engines were used to create the DB 606 A/B. The supercharger on the DB 601 Aa ran full speed at an altitude of 13,123 ft (4,000 m), and the engine had a compression ratio of 6.9 to 1. For takeoff and emergency power at 2,500 rpm and 20.6 psi (1.42 bar) of boost, the early DB 606 A/B V-series (Versuch, experimental) produced 2,350 hp (1,728 kW) at sea level and 2,200 hp (1,618 kW) at 12,139 ft (3,700 m). For climb and combat power at 2,400 rpm and 19.1 psi (1.32 bar) of boost, the engine produced 2,090 hp (1,537 kW) at sea level and 2,100 hp (1,545 kW) at 13,451 ft (4,100 m). For maximum continuous power at 2,300 rpm and 16.9 psi (1.17 bar) of boost, the engine produced 1,900 hp (1,397 kW) at sea level and 1,760 hp (1,294 kW) at 14,764 ft (4,500 m).

Because it was based on an existing engine, the DB 606 was developed quickly. The engine made its first flight in the He 119 in June 1937 with Gerhard Nitschke at the controls. The single DB 606 was installed in the He 119’s fuselage and drove the 14 ft 1 in (4.30 m) diameter, four-blade propeller via a long extension shaft. DB 606 V1 through V4 powered the four He 119 aircraft that were built, and the engine proved to be reliable in that airframe. One He 119 did crash on 16 December 1937 after a faulty fuel transfer valve caused the engine to quit.

Heinkel also selected the DB 606 to power its new long-range heavy bomber design, which was submitted to the RLM (Reichsluftfahrtministerium, or Germany Air Ministry) in response to their Bomber A specification. The RLM ordered construction of a prototype on 2 June 1937, and the aircraft was soon designated as the Heinkel He 177 Greif (Griffon). Like with the He 119, the He 177 was designed by Siegfried and Walter Günter, although Walter was killed in a car accident on 21 September 1937. As changes in the design requirements mounted, particularly with RLM’s insistence that the He 177 be capable of dive bombing, Siegfried was forced to alter the aircraft and make compromises to its design.

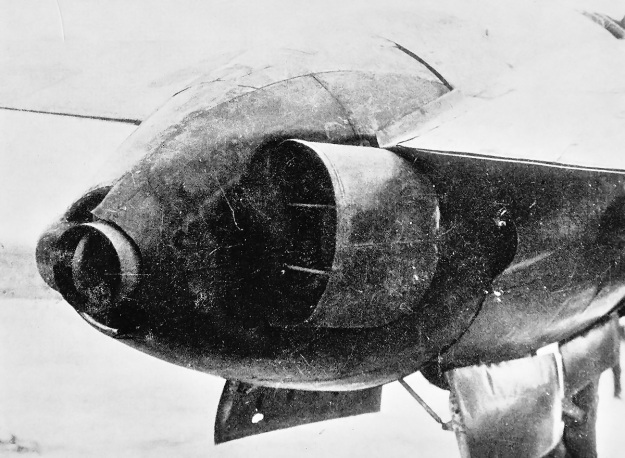

The DB 606 was designed for use buried in the fuselage of the Heinkel He 119 and powered the propeller via a long extension shaft. This aircraft (D-AUTE) was lost on 16 December 1937 following an engine failure due to a faulty fuel transfer valve.

Each of the He 177’s wings had one DB 606 engine installed fairly deep and immediately forward of the main landing gear. Each main gear consisted of two legs, with the inboard leg retracting toward the wing root and the outboard leg retracting toward the wing tip. Because of the cramped installation of the engine and landing gear, there was no firewall behind the DB 606. Room was at such a premium that right-angle fittings were used for connections behind the engine. Originally, surface cooling had been planned, but this was switched to annular radiators installed in the engine nacelle just before the engine. The DB 606’s extension shaft led from the engine, through the radiators, and to the He 177’s four-blade propeller, which was 14 ft 9 in (4.5 m) in diameter.

At least 800 He 177 aircraft had been ordered before the prototype made its first flight on 20 November 1939, piloted by Carl Francke. For reference, the He 177 prototype flew with engines V5 and V6, indicating just how few DB 606s had been produced up to that point. In December 1940, DB 606 A/B-1 engines uprated to 2,700 hp (1,986 kW) were installed in He 177 V6. The uprated DB 606 A/B-1 used two 1,350 hp (993 kW) DB 601 E engines. The supercharger of the uprated DB 601 E ran full speed at an altitude of 15,748 ft (4,800 m).

For takeoff and emergency power at 2,700 rpm and 20.9 psi (1.44 bar) of boost, the DB 606 A/B-1 produced 2,700 hp (1,986 kW) at sea level and 2,650 hp (1,949 kW) at 15,748 ft (4,800 m). For climb and combat power at 2,500 rpm and 19.1 psi (1.32 bar) of boost, the engine produced 2,400 hp (1,765 kW) both at sea level and at 16,076 ft (4,900 m). For maximum continuous power at 2,300 rpm and 16.9 psi (1.17 bar) of boost, the engine produced 2,000 hp (1,471 kW) at sea level and 2,075 hp (1,526 kW) at 16,732 ft (5,100 m).

Starting around 1940, Daimler-Benz used a lower compression ratio in the right (non-supercharger side) cylinder bank. This was due to the crankshaft’s rotation flinging extra oil toward the right cylinders. Some of the oil would get past the piston rings and into the combustion chamber. The presence of this oil increased the possibility of detonation (knock) in the cylinder. The compression ratio was decreased slightly to increase the cylinder’s knock resistance. Because the inner cylinder banks of the doppelmotoren were nearly vertical, they captured more oil than the outer cylinder banks. The inner banks also ran hotter because of their tight installation. The extra oil and the heat both increased the possibility of detonation in the inner cylinder banks. As a result, the inner cylinder banks of the doppelmotoren had a slightly lower compression ratio than that of the outer cylinder banks. For the DB 606 A/B-1, the outer (supercharger side) cylinder banks had a compression ratio of 7.2 to 1, and the inner (non-supercharger side) cylinder banks had a compression ratio of 7.0 to 1.

The Heinkel He 177 bomber was designed to take advantage of the reduced drag offered by the DB 606 doppelmotor. However, the engine and its installation proved to be very problematic. The He 177 A-02 pictured above was the tenth He 177 built and second production machine. It was lost in May 1942 during a crash landing after both engines caught fire.

The DB 606 engine and its installation in the He 177 proved to be disastrous. As doppelmotor production picked up, vibration issues were discovered with the two engine sections, and the combining gear required much more development than had been anticipated. There were also issues with failures of the engine couplings. A major DB 606 issue was with its oil circulation at high altitudes. The oil would foam, leading to inadequate lubrication and the subsequent failure of bearings and seizing of pistons. Some of these failures would be catastrophic, with parts (connecting rods) breaking through the crankcase.

But it was the engine installation that caused the biggest issues. The annular radiators provided inadequate cooling, resulting in the engines running hot. The exhaust between the two inner cylinder banks ran so hot that any fuel or oil that dripped down from leaking fittings or during a catastrophic engine failure was ignited. Weeping fittings and seeping seals (partly caused by material shortages and substitutions during the war) were a constant issue, as the leaked fluid would pool and eventually be ignited by the hot exhausts’ radiant heat. Through lack of a firewall, fires in the engine nacelle would spread to the main gear and ignite any leaking hydraulic fluid. In addition, the hot exhaust being expelled just forward of the extended main gear was enough to ignite any hydraulic oil that had leaked.

Any fire in the wing spread quickly and spelled disaster for the aircraft and its crew. With the crew siting well forward of the engines, fires often went unnoticed until severe damage had occurred. Despite the best efforts of maintenance crews, the DB 606 engines needed constant attention and proved very difficult to service. Engine fires occurred with such regularity that crews referred to the He 177 as the Luftwaffenfeuerzeug, or Luftwaffe’s cigarette lighter. To resolve the engine issues, suggestions were made to extend the engine nacelle, install a firewall, reroute lines to prevent the pooling of fluids under the engine, and redesign the exhaust system. Such changes were ignored at first because they would delay He 177 production, which had already been rushed. However, the aircraft was also experiencing a number of structural issues unrelated to the engines that made modifications necessary.

Toward the end of 1942, the He 177 underwent a redesign as the A-3 variant. This aircraft would do away with the troublesome DB 606 engines and replace them with DB 610s. The DB 610 was a doppelmotor consisting of two 1,475 hp (1,085 kW) DB 605 A engines. The DB 605 was a development of the DB 601 that operated at a higher RPM, had an increased bore, and had a higher compression ratio. The DB 605/610 used plain bearings for the connecting rods rather than the roller bearings used on the DB 601/606.

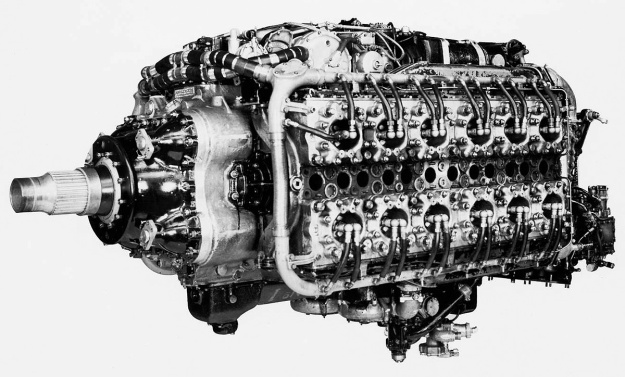

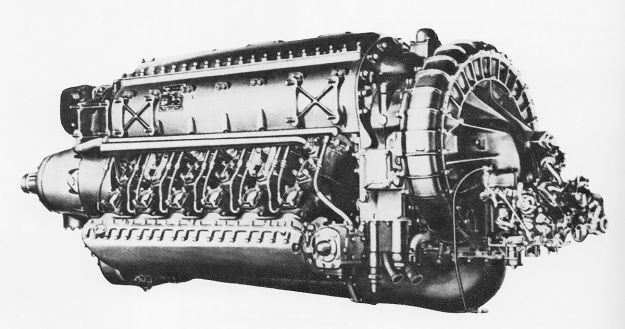

The DB 610 combined two DB 605 engines and was intended to cure the issues with the DB 606. While the DB 610 was more powerful, issues still persisted, and all doppelmotoren proved to be difficult to service and maintain. The propeller extension shaft was typical, being used on the He 177, Ju 288, and NC.3021.

The DB 610 kept the same engine section naming convention as the earlier doppelmotor, with the “W-Motor” (or DB 605 W) as the right section and the “X-Motor” (or DB 605 X) as the left section. The supercharger ran full speed at an altitude of 18,701 ft (5,700 m). The compression ratio of the outer (supercharger side) cylinder banks was 7.5 to 1, and the compression ratio of the inner (non-supercharger side) cylinder banks was 7.3 to 1.

The Daimler-Benz DB 610 A/B had a 6.06 in (154 mm) bore, a 6.30 in (160 mm) stroke, and a total displacement of 4,365 cu in (71.53 L). For takeoff and emergency power at 2,800 rpm and 20.9 psi (1.42 bar) of boost, the engine produced 2,950 hp (2,170 kW) at sea level and 2,700 hp (1,986 kW) at 18,701 ft (5,700 m). For climb and combat power at 2,600 rpm and 19.1 psi (1.32 bar) of boost, the engine produced 2,620 hp (1,927 kW) at sea level and 2,500 hp (1,839 kW) at 19,029 ft (5,800 m). For maximum continuous power at 2,300 rpm and 16.9 psi (1.17 bar) of boost, the engine produced 2,150 hp (1,581 kW) at sea level and 2,160 hp (1,589 kW) at 18,045 ft (5,500 m). The DB 610 was the same size as the DB 606: 6 ft 10 in (2.08 m) long, 5 ft 4 in (1.63 m) wide, and 3 ft 6 in (1.06 m) tall; however, it was around 130 lb (60 kg) heavier. The dry weight of the DB 610 A was 3,395 lb (1,540 kg), and the dry weight of the DB 610 B was 3,483 lb (1,580 kg).

The DB 610 installation on the He 177 A-3 was extended 200 mm (7.9 in) forward, and a firewall was incorporated behind the engine. On 22 March 1943, the DB 610 made its first flight in an He 177 (V19, VF+QA). Although reliability had been improved, engine fires still occurred, and the DB 610 suffered from the same engine coupling failures that had been experienced with the DB 606. In May 1942, Hermann Göring, commander of the Luftwaffe, made the following comment in reference to the He 177 and DB 606: “I have never been so furious as when I saw this engine. …Nobody mentioned this hocus-pocus with two welded-together engines to me at all.” By early 1944, plans were in motion to build He 177 with four separate engines, a suggestion that Heinkel had discussed back in late 1938 and proposed in mid-1939. Further production and development of the He 177 was abandoned on 1 July 1944. Once the Allies had landed on the continent, German aircraft production was focused on defensive fighters and attackers.

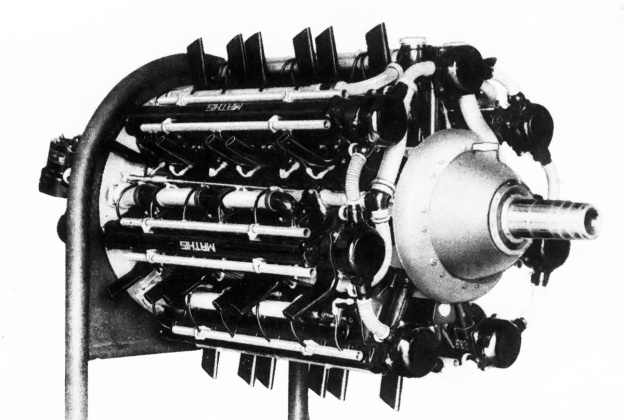

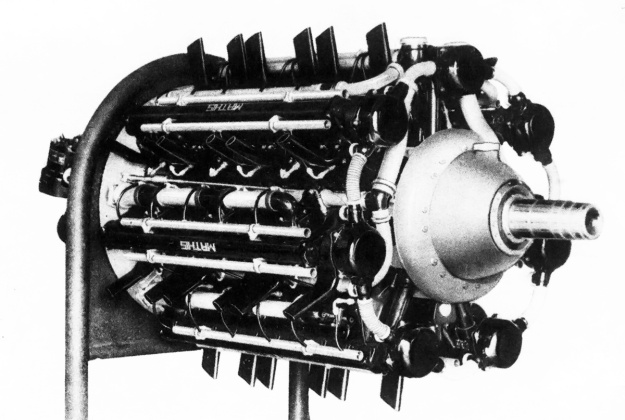

Side view of the DB 610 illustrates the relative ease with which the spark plugs on the outer cylinder banks can be accessed. However, one can imagine the extreme difficulty of accessing the spark plugs of the inner cylinder banks. The bolts on the upper side of the crankcase are the transverse bolts that pass through the main bearing caps.

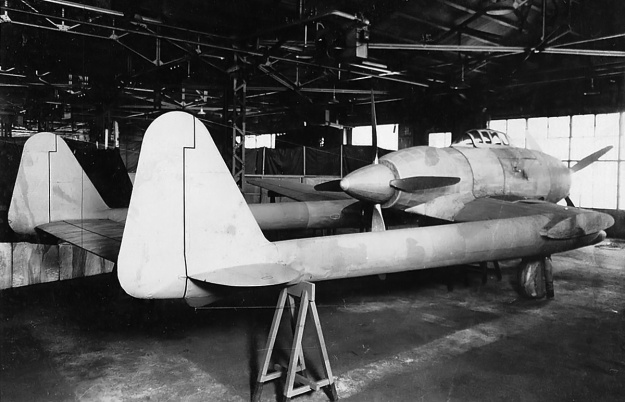

The Daimler-Benz doppelmotoren were also installed in the Junkers Ju 288 bomber. As issues with its intended 24-cylinder Junkers Jumo 222 inline radial engine created a short supply, the DB 606 was substituted in Ju 288 prototypes. A DB 606 engine was installed on each wing in a form-fitting nacelle with an annular radiator at its front. Like with the He 177, the extension shaft connected the engine to the propeller. The DB 606-powered Ju 288 V11 made its first flight in July 1942. Three additional Ju 288s were powered by DB 606 engines. A switch to the DB 610 was made for the Ju 288 V103, which was first flown in the spring of 1943. Five additional Ju 288s were powered with DB 610 engines. The doppelmotor installation in the Ju 288 did not result in the frequent engine fires experienced with the He 177. The DB 610 was planned for later Ju 288 C and D variants, but the aircraft were cancelled.

Post war, a DB 610 was used in the French SNCAC NC.3021 Belphégor high altitude research aircraft. The large single-engine aircraft had an annular radiator positioned in front of the DB 610 engine. The NC.3021 was first flown on 6 June 1946. Issues servicing the DB 610 were encountered, and the aircraft required much maintenance. SNCAC went bankrupt in mid-1949, and no other funds were provided for the aircraft. The NC.3021 was withdrawn from testing in 1950 and scrapped.

Development of the DB 613, a third doppelmotor, had a lower priority than that of the DB 606 and DB 610. With what appeared to be the successful creation of the DB 606, Daimler-Benz decided to apply the same doppelmotor concept to the DB 603 engine. The DB 603 was based on and built like the DB 601, but it had an enlarged bore and an elongated stroke. Compared to the DB 601, the DB 603 had slightly decreased supercharging at takeoff power but an increased compression ratio. The compression ratio of the outer (supercharger side) cylinder banks was 7.3 to 1, and the compression ratio of the inner (non-supercharger side) cylinder banks was 7.5 to 1.

When Junkers was unable to supply the needed numbers of the Jumo 222 engine, the DB 606 and DB 610 were used in its place to power the Junkers Ju 288 bomber. Ju 288 V103 seen above was probably the first Ju 288 to be powered by the DB 610.

Around 1940, the DB 613 was created by combining two 1,750 hp (1,287 kW) DB 603 G engines. The combining gear housing on the DB 613 was different that those used on the DB 606 and DB 610. The DB 613’s housing was asymmetric with an accessory drive from the W-Motor (right engine). The Daimler-Benz DB 613 A/B had a 6.38 in (162 mm) bore, a 7.09 in (180 mm) stroke, and a total displacement of 5,434 cu in (89.04 L). For takeoff and emergency power at 2,700 rpm and 21.5 psi (1.48 bar) of boost, the engine produced 3,600 hp (2,648 kW) at sea level and 3,100 hp (2,280 kW) at 22,966 ft (7,000 m). For climb and combat power at 2,500 rpm and 19.8 psi (1.37 bar) of boost, the engine produced 3,150 hp (2,317 kW) at sea level and 2,860 hp (2,104 kW) at 23,293 ft (7,100 m). For maximum continuous power at 2,300 rpm and 18.4 psi (1.27 bar) of boost, the engine produced 2,790 hp (2,052 kW) at sea level and 2,650 hp (1,949 kW) at 21,982 ft (6,700 m). The DB 613 was 7 ft 3 in (2.22 m) long without its extension shaft, 5 ft 10 in (1.77 m) wide, and 3 ft 9 in (1.14 m) tall. The dry weight of the DB 613 A was 4,321 lb (1,960 kg), and the dry weight of the DB 613 B was 4,409 lb (2,000 kg). The DB 613 was proposed for the Heinkel He 177 A-7 variant, but the aircraft was not produced, and the engine never progressed beyond the prototype stage. It is not believed that the DB 613 was ever flight tested.

C/D variants of each engine were planned, but it is not clear if they were ever built beyond prototype examples. Development of the C/D variants seemed to start toward the end of 1942. In general, the C/D variants produced more power, had increased critical altitudes, and were planned for 100 octane fuel. The DB 606 C/D produced 2,600 hp (1,912 kW) for takeoff and had a critical altitude of 19,029 ft (5,800 m).

The DB 610 C/D was based on the DB 605 D and had a compression ratio of 8.5 to 1 for the outer (supercharger side) cylinder banks and 8.3 to 1 for the inner (non-supercharger side) cylinder banks. For takeoff and emergency power at 2,800 rpm and 20.6 psi (1.42 bar) of boost, the DB 610 C/D produced 2,870 hp (2,111 kW) at sea level and 2,560 hp (1,883 kW) at 24,934 ft (7,600 m). For climb and combat power at 2,600 rpm and 19.1 psi (1.32 bar) of boost, the engine produced 2,550 hp (1,876 kW) at sea level and 2,400 hp (1,765 kW) at 24,278 ft (7,400 m). For maximum continuous power at 2,300 rpm and 17.6 psi (1.22 bar) of boost, the engine produced 2,100 hp (1,545 kW) at sea level and 2,050 hp (1,508 kW) at 22,966 ft (7,000 m). The dry weight of the DB 610 C was 3,461 lb (1,570 kg), and the dry weight of the DB 610 B was 3,538 lb (1,605 kg).

The SNCAC NC.3021 Belphégor was a high-altitude research aircraft that incorporated a pressurized cabin. Powered by a DB 610, the post-war aircraft carried a crew of three plus two researchers. It was the last aircraft design that used a Daimler-Benz doppelmotor.

The DB 613 C/D had the same compression ratio increase as the DB 610 C/D. For takeoff and emergency power at 2,900 rpm and 20.9 psi (1.44 bar) of boost, the DB 613 C/D produced 4,000 hp (2,942 kW) at sea level and 3,600 hp (2,648 kW) at 19,685 ft (6,000 m). For climb and combat power at 2,700 rpm and 19.1 psi (1.32 bar) of boost, the engine produced 3,500 hp (2,574 kW) at sea level and 3,280 hp (2,412 kW) at 19,685 ft (6,000 m). For maximum continuous power at 2,300 rpm and 17.6 psi (1.22 bar) of boost, the DB 613 C/D produced 2,850 hp (2,096 kW) at sea level and 2,860 hp (2,104 kW) at 17,388 ft (5,300 m).

The Daimler-Benz doppelmotoren represented a quick way to double an engine’s output without quite doubling the drag of installation. While the engines worked well in the He 119 and Ju 288, the engine package failed to work reliably in the He 177, which was the main application. A total of approximately 1,916 doppelmotoren were produced: 820 (544 by some sources) DB 606s, 1,070 (1,346 by some sources) DB 610s, and 26 DB 613s. The engines tested in a Junkers Ju 52 transport and powered four He 119s, 915 (1,135 by some sources) He 177s, ten Ju 288s, and one SNCAC NC.3021.

An early DB 606 A is displayed at the Technik Museum in Sinsheim, Germany. DB 610 engines are on display in Germany at the Deutsches Museum in Munich and the Luftfahrttechnisches Museum (Aviation Museum) in Rechlin; and in the United Kingdom at the Royal Air Force Cosford Museum in Shropshire and the Science Museum at Wroughton. Reportedly, a DB 610 is in France, but its location and condition have not been found. The Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum has in storage a DB 610 engine in a complete He 177 nacelle. A DB 610 combining gear reduction housing is on display at the Muzeum Lotnictwa Polskiego (Polish Aviation Museum) in Krakow, Poland. No DB 613 engines are known to have survived.

Note: The figures in this article listed as hp (horsepower) are actually PS (Pferdestärke, metric horsepower). The kW figures are converted from the PS value.

The DB 613 utilized two DB 603 engines. It was the largest, heaviest, and most powerful of the doppelmotoren. The DB 613 had an asymmetric combing gear housing that incorporated an accessory drive. The engine never progressed beyond prototype testing.

Sources:

– Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft 1945-46 by Leonard Bridgman (1946)

– Flugmotoren und Strahltriebwerke by Kyrill von Gersdorff, et. al. (2007)

– The Secret Horsepower Race by Calum E. Douglas (2020)

– Heinkel He 177 Greif by J. Richard Smith and Eddie J. Creek (2008)

– Junkers Ju 288/388/488 by Karl-Heinz Regnat (2004)

– Major Piston Engines of World War II by Victor Bingham (1998)

– DB 606 A-B Baureihe 0 u. 1 Motoren-Handbuch by Technisches Amt (November 1942)

– Ersatzteilliste für Mercedes-Benz-Flugmotor Baumust DB 606 A-B by Daimler Benz (December 1941)

– DB 610 A-B Baureihe 0 u. 1 Motoren-Handbuch by Technisches Amt (November 1942)

– Betriebs und Wartungsvorschrift zum Mercedes-Benz Flugmotor DB 601 A u. B by Daimler Benz (October 1940)

– Motorhandbuch zum Mercedes-Benz-Flugmotor DB 603 A Baureihe 0, 1 und 2 by Daimler Benz (November 1942)