By William Pearce

Clessie Lyle Cummins was a self-taught engineer. In 1911, he served on the pit crew for Ray Harroun’s #32 Marmon Wasp racer, which won the inaugural Indianapolis 500 race. Clessie went on to start the Cummins Engine Company in 1919 and specialized in diesel engines. The Cummins company struggled in its early years. Initially, Cummins engines found success powering yachts, but the company made efforts to break into the automotive field.

Clessie Cummins in Washington D.C. on tour after setting the diesel speed record at 100.755 mph (162.150 km/h) on 7 February 1931 in Daytona Beach, Florida. The car was slightly modified and entered in the 1931 Indianapolis 500 race. (Indiana Public Media image via flickr.com)

The Great Depression took its toll on Cummins and also affected auto racing. To increase race participation, Eddie Rickenbacker, then-owner of the Indianapolis Speedway and American Automobile Association Contest Board president, relaxed the racing rules to allow stock-block engines up to 366 cu in (6.0 L) in 1930. Cummins saw an opportunity to help fill the racing field and gain publicity in the Indianapolis 500 by fielding a diesel-powered racer in the 1931 race. Rickenbacker agreed to the plan and offered Cummins a provisional spot provided the racer could top 80 mph (129 km/h). However, the Cummins entry would not be entitled to any winnings, because of its guaranteed entry into the field.

Cummins contracted Augie Duesenberg to modify a Duesenberg Model A chassis and install a 4-cylinder Cummins Model U engine. The Model U was a marine engine with a 4.5 in (114 mm) bore, a 6.0 in (152 mm) stroke, and a displacement of 382 cu in (6.3 L). To make the engine conform to the displacement limit, the bore of the race engine was decreased by .125 in (3 mm), resulting in a bore of 4.375 in (111 mm). This resulted in a displacement of 361 cu in (5.9L). The engine had been modified with aluminum pistons and two intake valves but retained a single exhaust valve. The race engine produced 85 hp (63 kW) at 1,500 rpm and weighed about 1,600 lb (726 kg).

Clessie Cummins stands behind the Cummins Diesel Special #8 entered in the 1931 Indy 500. Dave Evans and Thane Houser are in the cockpit. Note the racer’s height. (IMS image)

To test the powertrain, Clessie drove the car to Daytona Beach, Florida and set a diesel flying-mile (1.6-km) speed record at 100.755 mph (162.150 km/h) on 7 February 1931. The racer was then driven to Washington D.C. and back to the Cummins factory, where it was modified in accordance with the Indy 500 rules. Its completed weight was a hefty 3,389 lb (1,537 kg).

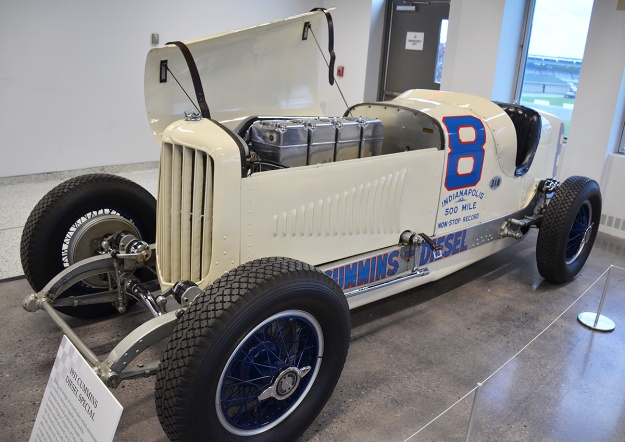

For the Indy 500, the car was named the Cummins Diesel Special and given race #8. Dave Evans was the driver with Thane Houser as the riding mechanic / co-driver. The Cummins Diesel Special was regularly driven the 45 miles (72 km) from the Cummins factory in Columbus, Indiana to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. The Cummins racer qualified at 96.871 mph (155.899 km/h), which was the 43rd fastest car. Since Rickenbacker had guaranteed a spot in the 40-car field, the Cummins Diesel Special was the slowest car in the 1931 Indianapolis 500. However, the Cummins team had a plan to pick up a few spots during the race.

The restored #8 displayed in the Indianapolis Motors Speedway Museum. Note the engine’s four individual cylinders. (Doctorindy image via Wikimedia Commons)

On race day, 30 May 1931, the Cummins Diesel Special was driven from the factory to the raceway. The racer proved to be slow during the 500-mile (805-km) competition, but the fuel-efficient engine enabled the Cummins Diesel Special to run the entire race without stopping, the first and only racer to accomplish such a feat during the Indy 500. In those days, the race continued after the first-place car finished until each car that could finish had completed the 200 laps. The Cummins Diesel Special completed its 200th lap and finished the race 38 minutes after the race leader, which was enough to secure a 13th place finish. The diesel-powered racer averaged 86.170 mph (138.677 km/h) over the 500-mile (805-km) distance, and the amount of fuel used reportedly cost $1.40 ($23 in 2018 USD).

In 1932, Clessie Cummins and William G. Irwin (Cummins’ main financial backer) took the racer on a 5,000-mile (8,047-km) tour of Europe. This trip resulted in some modifications to the racer, such as the addition of a windshield and headlights. The Duesenberg-built Cummins Diesel Special was preserved by Cummins and restored to its Indy-race configuration. The car is often displayed in various museums and run on rare occasion at special events.

Dave Evans and Jigger Johnson in the four-stroke #6 at Indy in 1934. The Roots supercharger can just be seen at the front of the car. (IMS image)

The Cummins Team returned in 1934 to race in the Indy 500. Cummins fielded two Duesenberg-chassis cars for the race, each powered by an experimental, supercharged, aluminum, inline-four engine. The engine had a 4.875 in (124 mm) bore and stroke and displaced 364 cu in (6.0L). The difference between the cars was primarily a difference in engines, with one car using a four-stroke engine and the other car using a two-stroke engine. The Indy 500 race served as a test to compare the two different combustion cycle engines. The Roots-type supercharger was driven from the engine and installed at the front of the car. The supercharger in the four-stroke car took about 7 hp (5 kW) to run, compared with 37 hp (28 kW) for the two-stroke car, which also used the supercharger for cylinder scavenging. The four-stroke engine had one intake valve and one exhaust valve. The two-stroke engine had two exhaust valves and intake ports in the cylinder that were uncovered by the piston. Each engine produced approximately 135 hp (101 kW) at 2,500 rpm. The engines each weighed about 1,000 lb (454 kg), and each car weighed around 3,200 lb (1,451 kg).

The #6 car with the Roots supercharger passing induction air through the radiator and to the engine. (IMS image)

The four-stroke car, race #6, was driven by Dave Evans with John ‘Jigger’ Johnson as the riding mechanic. It qualified in 22nd place at 102.414 mph (164.819 km/h). During the race, #6 made its first pitstop after 200 miles (322 km). Unfortunately, engine torque damaged the transmission as the racer quickly accelerated to reenter the track. This forced Evans and Johnson to retire from the race, and #6 was awarded 19th place. The engine in #6 had operated flawlessly during the race. The car has been preserved by Cummins and is occasionally displayed for special events.

The restored #6 car displayed in the Cummins Museum at the Company’s corporate headquarters in Columbus, Indiana. (Ricky Berkey image)

Clessie Cummins stands by the two-stroke #5 racer at Indy in 1934 with Stubby Stubblefield and Bert Lustig in the cockpit. The Roots supercharger can be seen through the car’s grille. The racer’s 12th place finish is the best for a diesel-powered car in the Indy 500. (Indiana Public Media image via flickr.com)

The two-stroke car, race #5, was driven by Stubby (Wilburn Hartwell) Stubblefield with Bert Lustig as the riding mechanic. The car qualified 29th at 105.921 mph (170.463 km/h). Although the two-stroke engine was temperamental, #5 went the distance and finished the 500-mile (805-km) race in 12th place, averaging 88.566 mph (142.533 km/h). Evans took over driving duties from Stubblefield around mid-race. Race #5 was the last car to complete the 200 laps—finishing the race trailing smoke and overheating. After the racer was shut down, the pistons seized in the cylinders. Some sources indicate that Clessie was so displeased with the two-stroke engine that it was tossed into a river as the team made its way back to Columbus. Because of the issues with the two-stroke engine, Cummins subsequently abandoned two-stroke development and focused on four-stroke engines.

After Indy, a four-stroke, six-cylinder engine was installed in the #5 racer. Wild Bill Cummings set diesel speed records on Daytona Beach Florida in 1935 and is seen behind the wheel. The front of the car was stretched to accommodate the longer engine. Note the six-to-one exhaust manifold. (Cummins image)

Race #5 was later modified (lengthened) to accommodate a four-stroke, six-cylinder engine. Wild Bill Cummings used the updated #5 to set a flying-mile (1.6 km) diesel speed record of 133.023 mph (214.080 km/h) on 1 March 1935. The following day, Cummings increased the record speed to 137.195 mph (220.794 km/h). Cummings in Race #5 also set 5 km (3.1 mi) and 5 mi (8.0 km) records of 126.99 mph (204.37 km/h) and 112.07 mph (180.36 km/h) respectively. However, the event was not sanctioned, and none of these records were internationally recognized. Race #5 was preserved by Cummins in its record-setting form and is occasionally displayed in various museums.

The restored #5 in its Daytona configuration with a four-stroke, six-cylinder engine. The car was displayed for a time at the Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg Museum on account of its Duesenberg chassis. As seen above, #5 is at the Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance in April 2019. (The Southern Concours / John E. Adams image)

It was not until 1950 that Cummins returned to the Indy 500. The car was called the Cummins Diesel Special (just like the 1931 entry) and wore race #61. Because of its green color, driver Jimmy Jackson referred to the car as the Green Hornet. The racer consisted of a modified Kurtis Kraft chassis powered by a supercharged inline-six engine based on the Cummins JBS-600 truck engine. The car used disc brakes, which was a first at Indy.

Jimmy Jackson sits in the 1950 Cummins Diesel Special #61 at Indy. Although much more refined compared to the earlier racers, #61 was still a heavy brute compared to the rest of the field. Induction air was brought in via the front tunnel. The scoop on the engine cowling provided clearance for the cylinder head and airflow to help cool the engine, but overheating was still a problem. (IMS image)

The Roots-type supercharger was crankshaft-driven and mounted in front of the engine. The special engine had four-valves per cylinder and used an aluminum crankcase, cylinder block, and head. Two injectors delivered fuel into each cylinder, and the engine used an early design of what would become Cummins’ PT (Pressure-Timed) fuel injection. The engine had a 4.125 in (105 mm) bore and a 5.0 in (127 mm) stroke. It displaced 401 cu in (6.6 L) and produced 320 hp (239 kW) at 4,000 rpm. With the ram-air effect of the racer at speed providing additional boost, the engine’s output increased to 340 hp (254 kW) at 4,000 rpm. The engine weighed 860 lb (390 kg).

The uncowled #61 with Jackson in the cockpit. Note the crossflow head with the intake manifold on one side and the exhaust manifold on the other. The earlier Indy racers had the intake and exhaust manifolds on the same side (passenger) of the engine. The car’s independent front suspension was a first at Indy. (Motor Trend image)

Despite some difficulty, the diesel-powered Green Hornet eventually qualified for the Indy 500 at 129.208 mph (207.940 km/h), the slowest qualifying speed of the grid. During the race, the car was retired on lap 52, while in 29th place, because of issues with the engine’s vibration damper and supercharger drive. Repaired, and at the Bonneville Salt Flats on 11 September 1950, Jackson and the Green Hornet set six International diesel speed records: 163.82 mph (263.64 km/h) over 1 km (.6 mi), 165.23 mph (265.91 km/h) over 1 mile (1.6 km), 164.25 mph (264.33 km/h) over 5 km (3.1 mi), 161.92 mph (260.59 km/h) over 5 mi (8.0 km), 147.63 mph (237.59 km/h) over 10 km (6.2 mi), and 148.14 mph (238.41 km/h) over 10 mi (16 km). The previous diesel records up to 5 km (3.1 mi) were set by George Eyston and the Flying Spray in April 1936. The previous 5 km (3.1 mi) and 5 mi (8.0 km) records were those set by Wild Bill Cummings and Race #5 in March 1935. The Green Hornet was preserved by Cummins and is often displayed in various museums. On rare occasions, the car is run at special events.

The 1950 racer was nicknamed Green Hornet on account of its paint. After Indy, #61 and Jackson set six diesel speed records at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah. The Green Hornet is pictured as displayed in the Indianapolis Motors Speedway Museum. (AutoDesign image)

In 1951, Cummins decided to make a serious attempt for the 1952 Indy 500. Clessie’s brother Don Cummins headed the team, with Nev Reiners as the chief engineer. Also on the team were Thane Houser (riding mechanic / co-driver for the 1931 Indy effort), Bill Doup, Mike Fellows, Art Eckleman, and Joe Miller. The Cummins Team worked directly with Frank Kurtis of Kurtis Kraft to design a low-slung chassis, and every opportunity was taken to exploit the chassis-engine combination.

Freddie Agabashian and crew with the 1952 Cummins Diesel Special #28 at Indy. The engine installed on its side made the car a low and sleek racer. Compare #28’s height with that of the earlier racers. (IMS image)

Powering the new racer was a further development of the JBS-600-based engine used in the Green Hornet. Since the new engine was turbocharged, it is often referred to as a modified JT-600. The engine consisted of a magnesium crankcase with an aluminum cylinder bank and head. Concepts from Cummins’ NHH-series engines (inline-six laid on its side) were applied to the race engine, and it was installed in the racer’s chassis laid over at an 85-degree angle—nearly on its side. This resulted in a very low engine cowling about 23 in (.58 m) above the ground. The turbocharger was installed in front of the engine on the right side of the car and provided up to 20 psi (1.38 bar) of boost. Like with the Green Hornet, a precursor to the Cummins’ PT fuel injection system was employed. The engine had a 4.125 in (105 mm) bore, a 5.0 in (127 mm) stroke, and a displacement of 401 cu in (6.6 L). The power produced was 380 hp (283 kW) at 4,000 rpm and 430 hp (321 kW) at 4,500 rpm. The engine weighed around 750 lb (340 kg).

The crankshaft, transmission, and driveline were on the left side of the car, putting 150 lb (68 kg) of weight bias on the left side of the car for better handling around the oval track. The cockpit was offset to the right, and the driver’s position was very low, only 4 in (102 mm) off the ground. The racer’s configuration resulted in a very low center of gravity, but the car was quite heavy at around 3,100 lb (1,406 kg). The turbocharger was a first at Indy, as was the offset drivetrain and the car’s independent front suspension. The aerodynamics of the chassis and bodywork were fine-tuned in a wind tunnel, which was reportedly another Indy first.

With the body removed, the compact nature of #28’s chassis is revealed. The turbocharger can just be seen between the front tires. On the left side of the car, note the underside of the crankcase and the driveline extending to the rear. (Cummins image)

The car was completed in late 1951, and testing began in November. Again christened as the Cummins Diesel Special, the car was given race #28 and was driven by Freddie Agabashian. Early testing indicated a very fast car, and Agabashian was careful not to reveal the racer’s full potential during practice sessions at Indy. Agabashian would not run full power for complete laps because there was some concern that the car would be banned had its true, competitive speed been reached. Fifteen minutes before the end of Pole Day qualifying, Agabashian took #28 out and set a one-lap record at 139.104 mph (223.866 km/h) and a

four-lap record at 138.010 mph (222.106 km/h). Agabashian and #28 had qualified in 1st place in a diesel. Agabashian had pushed the racer so hard that he tore the tread off some of the tires. The qualifying record was short-lived, as two cars later qualified with faster speeds, but it was still a major accomplishment for the Cummins Team.

On 30 May 1952, the Indy 500 was run. Agabashian in #28 found the diesel slower to accelerate than the other cars. Another problem cropped up with a buildup of tire rubber debris clogging the turbocharger intake. This issue ultimately caused the turbocharger to fail and forced #28 to retire on lap 71. At that point, Agabashian was in 5th place and had averaged 131.5 mph (211.6 km/h). The race was eventually won at a 130.843 mph (210.571 km/h) average, indicating #28 was keeping pace. Race #28 was credited with a 27th place finish. In short order, rules were changed, and the Cummins Diesel Special was the last diesel-engine racer to compete in the Indy 500.

Agabashian and #28 set off from the pits at Indy for a practice run. Unlike racers of today, the smoke at the back of the car is diesel smoke exhaust and not tire smoke. Note the indentation ahead of the front tire. The body was so wide that body indentations were needed for full lock tire clearance. (Cummins image)

Race #28 was returned to the Cummins factory in Columbus, Indiana where it was preserved. A restoration in 1968 revealed that the crankshaft had cracked and would have failed completely had the turbocharger issues not brought a halt to #28’s race. The racer was occasionally run for special events until 1999. In 2016, the Cummins Diesel Special underwent a restoration and was run for the first time since 1999. The racer is often displayed at the Cummins Museum and run on rare occasion at special events.

In each of its four outings at Indy, Cummins took advantage of rules that enabled the displacement of diesels to be up to twice that of spark-ignition engines. While this did offer an advantage for diesels, nearly everything else about the engine was a disadvantage compared to the standard racers. Cummins used the Indy 500 to showcase its diesel engines, test new technology, and make a statement about diesel power.

After its 2016 restoration, #28 participated in the 2017 Goodwood Festival of Speed in Chichester, UK. Bruce Watson, a retired Cummins Engineer, is driving the racer and also led the car’s restoration. (Steve Siler / Car and Driver image)

A sponsorship agreement between Cummins and the Indianapolis Motor Speedway will provide for all five diesel Indy cars to make a parade lap before the 2019 Indy 500. The event, which coincides with Cummins’ 100-year anniversary, will be the first time that the five cars have run together.

All five of the Cummins Diesel Indy Cars on display in May 2019 prior to the Indy 500 race. (Cummins image)

Sources:

– “Cummins at the Brickyard” by Karl Ludvigsen, Car Life (July 1969)

– “Diesels at Speed” by Griffith Borgeson, Motor Trend (December 1950)

– “The Triumph of the Diesel” Popular Mechanics (July 1934)

– http://www.trucktrend.com/cool-trucks/0808dp-cummins-diesel-race-car/

– http://www.trucktrend.com/news/1605-cummins-wakes-1952-diesel-special-indy-car-after-years-of-slumber/

– http://triplettracehistory.blogspot.com/2016/01/the-1931-cummins-diesel-photo-by-author.html

– https://www.allpar.com/corporate/bios/cummins.html

– https://stevemckelvie.wordpress.com/2011/06/05/the-cummins-diesel-special-at-the-1952-indianapolis-500/

– https://www.thetruthaboutcars.com/2015/10/clessie-cummins-made-diesels-king-road-almost-indy-part-one/

– https://www.thetruthaboutcars.com/2015/10/clessie-cummins-made-diesels-king-road-almost-indy-part-two/

– https://www.cummins.com/company/history/indianapolis-500

– https://www.caranddriver.com/features/when-cummins-diesels-assaulted-indy-feature

– https://www.conceptcarz.com/vehicle/z15198/duesenberg-cummins-diesel-indy-racer.aspx

– https://www.hemmings.com/blog/index.php/2011/08/02/diesels-at-daytona/

– https://cumminsengines.com/No-28-cummins-diesel-special-to-run-with-moto

– https://www.hotrodhotline.com/feature/heroes/landspeedracing/2009/09newsletter122/

Nice job. Thanks for the research.

I wish the torque output were included with the horsepower numbers, this is diesel after all.

Hello Kurbycar32,

I wanted to include the torque values, but I could not find any. Since we have hp and rpm, we can calculate the torque value. However, this would be the torque produced at the given power output and not necessarily the peak torque value. Since peak torque is not known, I did not want to include a torque value that needed an explanation every time it was used. But with the disclaimer out of the way, below are the torque values for the given engine outputs.

1931 #8:

85 hp (63 kW) at 1,500 rpm = 298 lb-ft (404 Nm)

1934 #5 and #6:

135 hp (101 kW) at 2,500 rpm = 284 lb-ft (385 Nm)

1950 #61:

320 hp (239 kW) at 4,000 rpm = 420 lb-ft (570 Nm)

340 hp (254 kW) at 4,000 rpm with ram-air = 446 lb-ft (605 Nm)

1952 #28:

380 hp (283 kW) at 4,000 rpm = 499 lb-ft (676 Nm)

430 hp (321 kW) at 4,500 rpm = 502 lb-ft (680 Nm)

any idea on the compression ratios? and more boost pressure info? Also, how did the rules change vis a vis compression ignition? seems fair that the displacement should be more (for diesels) given the rpm is limited. I would expect that the chassis changes were popularized throughout the roadsters until mid engines arrived with Coventry Climax in 1961.

Sorry, I do not know the compression ratios or boost pressures. The rules changed to restrict compression ignition engines to the same displacement as the spark ignition engines.

Hi my name is kevin jackson, jimmy jackson sr was my grandfather, im proud of what he accomplished, he taught me alot on working on cars. I have alot of his racing artifacts. Pics of him setting the records at boniville, and all the stuff from indy.

Hello Kevin – Glad to hear that you are keeping the memories and mementos alive. Proud it what you should be, and pass it along to the next generation. Kind regards.