By William Pearce

Inspired by Charles Lindbergh’s New York to Paris transatlantic flight of 3,600 miles (5,800 km) in May 1927, Italian pilot Arturo Ferrarin discussed with Alessandro Marchetti the possibility of building an aircraft to set non-stop distance records. Ferrarin was an experienced long distance flyer, having flown from Rome to Tokyo in 1920. Marchetti was the chief designer for Savoia-Marchetti and had complete control of the aircraft’s design and configuration. What emerged from Marchetti’s drafting table was the S.64. The Italian Air Ministry supported the project as a way to demonstrate the capabilities of Italian aviation to the world; two S.64 aircraft were ordered in late 1927.

The Savoia-Marchetti S.64 taking off from Montecelio. The retractable radiator can be seen under the wing and just behind the fuselage nacelle.

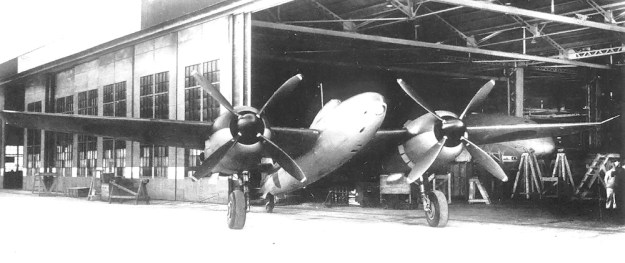

The Savoia-Marchetti S.64 was an aircraft of a rather unorthodox configuration yet similar to Marchetti’s earlier flying boat design, the S.55. Unlike the twin-hulled S.55 flying boat, the S.64 was a landplane. The S.64 consisted of a large, thick cantilever wing. A fuselage nacelle was blended into the center of the wing. The nacelle protruded below the wing and extended beyond its leading edge, but it was part of the wing’s structure. The pilot and copilot sat side-by-side and were provided with a rest area for long-distance flights. The wing and fuselage nacelle were made of wood and skinned with plywood. The wing housed 27 fuel tanks that combined to accommodate 1,717 gallons (6,500 L) of fuel.

Two frame booms made of duralumin extended behind the wing and supported the S.64’s slab horizontal stabilizer. Attached to the center of the horizontal stabilizer was the vertical stabilizer and rudder. Large control surfaces were attached to the trailing edge of both the horizontal and vertical stabilizers. Reportedly, the incidence of the horizontal and vertical stabilizers could be adjusted to trim the aircraft. The fixed main gear was faired and was suspended via struts under the wing. A tail skid was attached to the end of each boom.

A single FIAT A.22T V-12 engine was supported on struts above the wing. The FIAT A.22T was liquid-cooled and had a 5.3 in (135 mm) bore and 6.3 in (160 mm) stroke. The engine displaced 1,677 cu in (27.5 L) and produced 550 hp (410 kW). With the exception of its valve covers, the engine was encased in a streamlined cowl. At the very front of the cowl was a large oil tank for the engine. The pusher engine turned a two-blade wooden propeller with a streamlined, pointed spinner. Coolant from the engine traveled down the supporting struts into a radiator under the rear of the wing. The semi-retractable radiator could be extended below the wing for increased airflow.

The S.64 had a 70.5 ft (21.5 m) wingspan and was 34.1 ft (10.4 m) long. The aircraft had an empty weight of 5,291 lb (2,400 kg). Its useful load was 10,141 lb (4,600 kg), resulting in a maximum weight of 15,432 lb (7,000 kg)—nearly three times its empty weight. Its top speed was 146 mph (235 km/h), and cruise speed was around 100 mph (160 km/h). Takeoff speed with a heavy load was 93 mph (150 km/h). The S.64’s maximum range was estimated as 7,146 miles (11,500 km).

The first S.64, registered as I-SAAV, was first flown on 3 April 1928 at Cameri airfield in northern Italy by Alessandro Passeleva. The aircraft was then flown by Arturo Ferrarin and Carlo Del Prete, two men who would become very experienced in the S.64. Initial flight tests revealed the aircraft had a high takeoff speed that necessitated a smooth runway. On 18 April, Ferrarin flew the S.64 to Aeroporto Alfredo Barbieri in Montecelio, near Rome, where a special 4,265 ft (1,300 m) runway had been prepared. The beginning of the runway was paved and had a 6.5 percent grade to aid the aircraft’s initial acceleration. The rest of the runway had a 0.56 percent grade and was unpaved. Flight testing continued with progressively larger fuel loads, and a larger 9.8 ft (3.0 m) diameter propeller was fitted

On 31 May, Ferrarin and Del Prete took off with 921 gallons (3,486 L) of fuel in an attempt to set a new closed circuit distance record. The circuit was from Casale dei Prati in Montecelio to the tower at Torre Flavia (west to the coast) then south to the lighthouse at Anzio (by the coast) and back to Montecelio. After 58 hours and 34 minutes, Ferrarin and Del Prete landed at Montecelio on 2 June after traveling 4,763.82 miles (7,666.62 km) at an average speed of 86.48 mph (139.18 km/h). The S.64, with Ferrarin and Del Prete, had set new records for endurance, distance, and speed over a 5,000 km course. The S.64 beat the endurance record set by Americans Edward Stinson and George Haldeman, who flew for 53 hours and 35 minutes in a Stinson Detroiter aircraft in late March 1928.

A side view of the S.64 bis illustrating the duralumin booms that attached the tail to the rest of the aircraft.

The S.64 was then prepared for its next record flight—a straight-line flight of over 5,800 miles (9,300 km) from Montecelio to Rio de Janerio, Brazil. However, that plan was changed on account of high temperatures in Montecelio that would have necessitated a longer takeoff run. The runway at Montecelio had already been extended by 1,312 ft (400 m); its length was now 5,577 ft (1,700 m), but that would not be enough. The new destination was Bahia (now Salvador), Brazil, some 5,280 miles (8,500 km) away. The shorter flight allowed the fuel load to be reduced by 370 lb (168 kg), from 8,377 lb (3,800 kg) to 8,007 lb (3,632 kg).

On the evening of 3 July, Ferrarin and Del Prete departed Montecelio and headed southwest. The S.64 traveled toward Gibraltar and then headed down the coast of Africa and out across the Atlantic. On the afternoon of 5 July, Ferrarin and Del Prete crossed the Brazilian coastline, only to discover thick fog below. After searching in vain for a landing strip, they went back to the coast and set the S.64 down on the beach near Touros, Brazil. Landing in the sand damaged the S.64’s landing gear and fuselage. Not accounting for the distance flown looking for a landing strip, the S.64 set a new straight-line distance record of 4,466.58 miles (7,188.26 km). The flight was 49 hours and 15 minutes. Later, the S.64 was taken by ship to Rio de Janerio and donated to Brazil. (Unfortunately, Del Prete died in Brazil on 16 August 1928 from injuries suffered in the crash of another aircraft. A monument honoring Del Prete and the S.64’s flight was built in the Praça Carlo Del Prete in Laranjeiras, Rio – Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.)

Later in July after the S.64’s flight to Brazil, the Germans took the S.64’s endurance record with Johann Risztics and Wilhelm Zimmermann flying for 65 hours and 25 minutes in a Junkers W 33. Italy wanted the record back, and so the second S.64 was built. Finished in early 1929, the aircraft was designated S.64 bis to indicate changes made from the first S.64. The S.64 bis had a longer windscreen and a variable-pitch metal propeller.

Umberto Maddalena and Fausto Cecconi were selected to fly the S.64 bis, registered as I-SAAT. While flight testing was delayed in late 1929 because of bad weather, the French pilots Dieudonné Costes and Paul Codos took the S.64’s distance record. Flying in a Breguet 19 in mid-December, Costes and Codos traveled 4,989.26 miles (8029.44 km). Now the challenge was to set new endurance and distance records, and the S.64 bis would not disappoint.

On 30 May 1930, Maddalena and Cecconi took off from Montecelio in the S.64 bis and followed the same closed circuit course that the S.64 had traveled. Landing on 2 June (the second anniversary of Ferrarin and Del Prete’s flight), Maddalena and Cecconi and the S.64 bis were the new endurance and distance record holders. Their 67 hour, 13 minute, and 55 second flight had covered 5,088.28 miles (8,188.80 km).

Unfortunately the S.64 bis would set no additional records. On 19 March 1931, Maddalena and Cecconi and radio operator Giuseppe Da Monte embarked on a flight from Cinisello (near Milan) to Montecelio. About halfway into their flight, near Pisa, a failure occurred and the S.64 bis crashed into the sea off Calambrone. It is believed that the FIAT’s crankshaft broke, allowing the propeller to cut into the wing and fuselage nacelle of the S.64 bis. However, a definitive cause was never found. Tragically, Maddalena, Cecconi, and Da Monte were killed in the crash.

The Carlo Del Prete memorial in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. A sculpture of the S.64 flies above a stature of Carlo Del Prete as he stands before a plaque detailing the record flight. (Silvio Cezar Scremin image)

Sources:

– Aeroplani S.I.A.I. 1915-1930 by Giorgio Bignozzi and Roberto Gentilli (1982)

– SIAI Pagine Di Storia (1976)

– Italian Civil and Military Aircraft 1930-45 by Jonathan W. Thompson (1963)

– Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft 1931 by C. G. Grey (1931)

– “The Rome—Brazil Non-Stop Flight” Flight (12 July 1929)

– “Well-known Italian Pilots Killed” Flight (27 March 1931)

– “The Accident to the S.64” Flight (3 April 1931)

– http://archive.is/cNtFo

– http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Savoia-Marchetti_S.64