By William Pearce

In late 1924, the Italian firm Isotta Fraschini responded to a Ministero dell’Aeronautica (Italian Air Ministry) request for a 500 hp (373 kW) aircraft engine by designing the liquid-cooled, V-12 Asso 500. Designed by Giustino Cattaneo, the Asso 500 proved successful and was used by Cattaneo as the basis for a line of Asso (Ace) engines developed in 1927. Ranging from a 250 hp (186 kW) inline-six to a 750 hp (559 kW) W-18, the initial Asso engines shared common designs and common parts wherever possible.

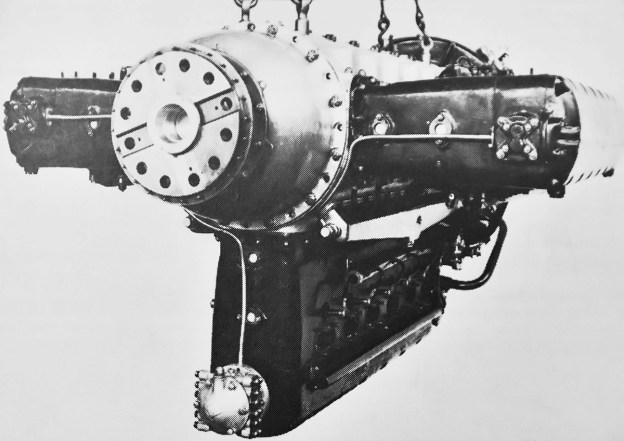

The direct drive Isotta Fraschini Asso 750 was the first in a series of 18-cylinder engines that would ultimately be switched to marine use and stay in some form of production for over 90 years.

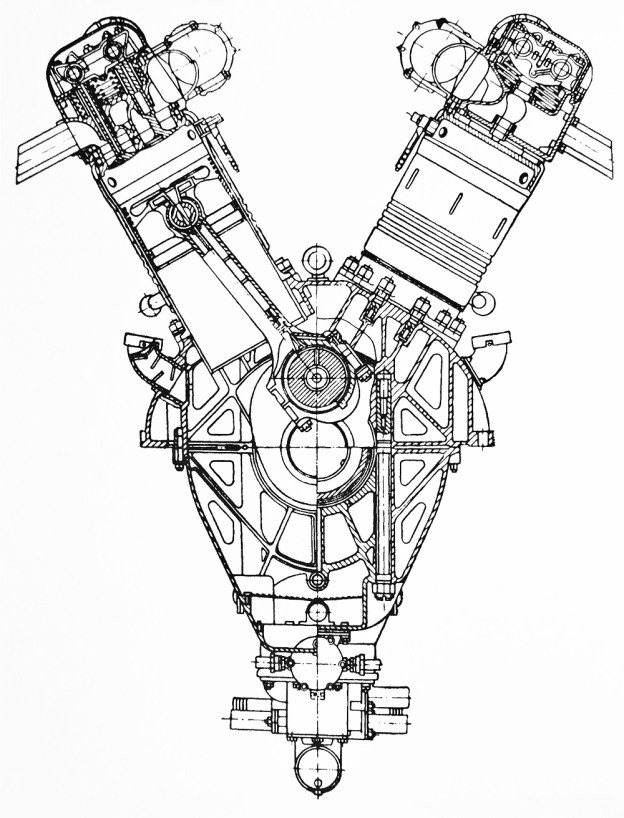

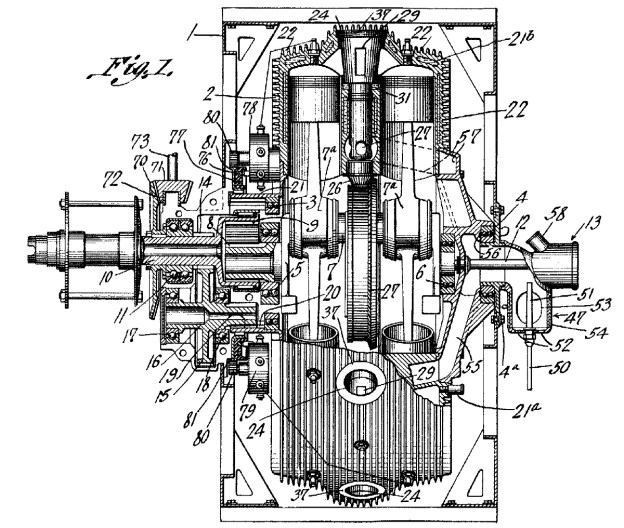

The Isotta Fraschini Asso 750 W-18 engine consisted of three six-cylinder banks mounted to a two-piece crankcase. The center cylinder bank was in the vertical position, and the two other cylinder banks were spaced at 40 degrees from the center bank. The cylinder bank spacing reduced the 18-cylinder engine’s frontal area to just slightly more than a V-12.

The Asso 750’s crankcase was split horizontally at the crankshaft and was cast from Elektron, a magnesium alloy. A shallow pan covered the bottom of the crankcase. The six-throw crankshaft was supported by eight main bearings. On each crankshaft throw was a master rod that serviced the center cylinder bank. Articulating rods for the other two cylinder banks were mounted on each side of the master rod. A double row ball bearing acted as a thrust bearing on the propeller shaft and enabled the engine to be installed as either a pusher or tractor.

The individual cylinders were forged from carbon steel and had a steel water jacket that was welded on. The cylinders had a closed top with openings for the valves. The monobloc cylinder head was mounted to the top of the cylinders, with one cylinder head serving each bank of cylinders. The cylinder compression ratio was 5.7 to 1. The cylinder head was made from cast aluminum and held the two intake and two exhaust valves for each cylinder. The valves were actuated by dual overhead camshafts, with one camshaft controlling the intake valves and the other camshaft controlling the exhaust valves (except for the center bank). A single lobe on the camshaft acted on a rocker and opened the two corresponding valves for that cylinder. The camshafts for each cylinder bank were driven at the rear of the cylinder head. One camshaft of the cylinder bank was driven via beveled gears by a vertical drive shaft, and the second camshaft was geared to the other driven camshaft. The valve cover casting was made from Elektron.

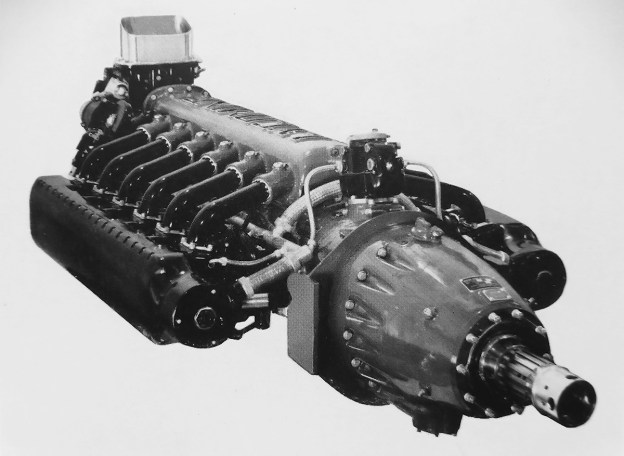

The cylinder row, upper crankcase, and cylinder head (inverted) of an Asso 750 RC35 with gear reduction. The direct drive Asso 750 was similar except for the shape of the front (right side) of the crankcase. Note the closed top cylinders. The small holes between the studs in the cylinder top were water passageways that communicated with ports on the cylinder head.

Three carburetors were mounted to the outer side of each outer cylinder bank. The intake and exhaust ports of the outer cylinder banks were on the same side. The intake and exhaust ports of the center cylinder bank were rather unusual. When viewed from the rear, the exhaust ports for the rear three cylinders of the center bank were on the right, and the intake ports were on the left. The front three cylinders were the opposite, with their exhaust ports on the left and their intake ports on the right. This configuration gave the cylinders for the center bank crossflow heads, but it also meant that each camshaft controlled half of the intake valves and half of the exhaust valves. A manifold attached to the inner side of the left cylinder bank collected the air/fuel mixture that had flowed through passageways in the left cylinder head and delivered the charge to the rear three cylinders of the center bank. The right cylinder bank had the same provisions but delivered the mixture to the front three cylinders of the center bank. Presumably, the 40-degree cylinder bank angle did not allow enough room to accommodate carburetors for the middle cylinder bank.

The two spark plugs in each cylinder were fired by two magnetos positioned at the rear of the engine and driven by the camshaft drive. From the rear of the engine, the firing order was 1 Left, 6 Center, 1 Right, 5L, 2C, 5R, 3L, 4C, 3R, 6L, 1C, 6R, 2L, 5C, 2R, 4L, 3C, and 4R. A water pump positioned below the magnetos circulated water into a manifold along the base of each cylinder bank. The manifold distributed water into the water jacket for each individual cylinder. The water flowed up through the water jacket and into the cylinder head. Another manifold took the water from each cylinder head to the radiator for cooling. Starting the Asso 750 was achieved with an air starter.

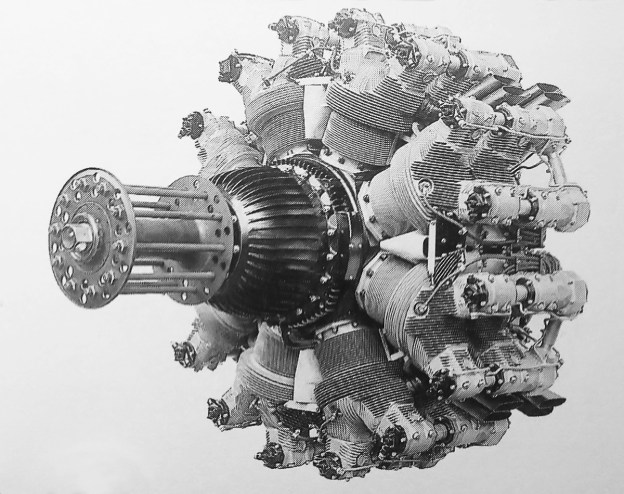

Two views of the direct drive Asso 750 displayed at the Museo nazionale della scienza e della tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci in Milan. Note the three exhaust stacks visible on the center cylinder bank. The front image of the engine illustrates the lack of space between the cylinder banks, which were set at 40 degrees. (Alessandro Nassiri images via Wikimedia Commons)

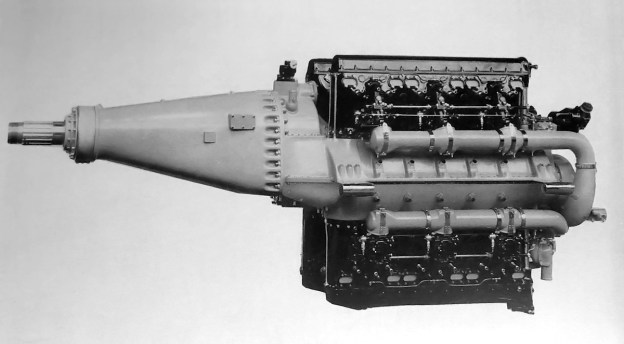

The Isotta Fraschini Asso 750 had a bore of 5.51 in (140 mm), a stroke of 6.69 in (170 mm), and a total displacement of 2,875 cu in (47.1 L). The original, direct drive Asso 750 produced 750 hp (599 kW) at 1,600 rpm, and weighed 1,279 lb (580 kg). An improved version of the Asso 750 was soon built that produced 830 hp (619 kW) at 1,700 rpm and 900 hp (671 kW) at 1,900 rpm. This engine weighed 1,389 lb (630 kg). The direct drive Asso 750 was 81 in (2.06 m) long, 40 in (1.02 m) wide, and 42 in (1.07 m) tall.

A version of the Asso 750 with a spur gear reduction for the propeller was developed and was sometimes referred to as the Asso 850 R. Available gear reductions were .667 and .581, and the gear reduction resulted in the crankshaft having only seven main bearings. The Asso 850 R produced 850 hp (634 kW) at 1,950 rpm, and weighed 1,455 lb (660 kg). This engine was also further refined and given the more permanent designation of Asso 750 R. The 750 R had a .658 gear reduction. The engine produced 850 hp (634 kW) at 1,800 rpm and 930 hp (694 kW) at 1,900 rpm. The Asso 750 R was 83 in (2.12 m) long and weighed 1,603 lb (727 kg).

Front view of the Asso 750 RC35. The gear reduction required new upper and lower crankcase halves and a new crankshaft, but the other components were interchangeable with the direct drive engine.

Around 1933 the Asso 750 R engine was updated to incorporate a supercharger. The new engine was designated Asso 750 RC35. The “R” in the engine’s designation meant that it had gear reduction (Riduttore de giri); the “C” meant that it was supercharged (Compressore); and the “35” stood for the engine’s critical altitude in hectometers (as in 3,500 meters). The engine’s water pump was moved to a new mount that extended below the oil pan. The supercharger was mounted between the water pump and the magnetos, which were moved to a slightly higher location. The supercharger was meant to maintain sea level power up to a higher altitude, and it provided .29 psi (.02 bar) of boost up to 11,483 ft (3,500 m). The Asso 750 RC35 produced 870 hp (649 kW) at 1,850 rpm at 11,483 ft (3,500 m). The engine was 87 in (2.20 m) long, 41 in (1.03 m) wide, 48 in (1.21 m) tall, and weighed 1,724 lb (782 kg).

In 1928, Isotta Fraschini designed a larger, more powerful engine that had both its bore and stroke increased by .39 in (10 mm) over that of the Asso 750. The larger engine was developed especially for the Macchi M.67 Schneider Trophy racer. The M.67’s engine was initially designated Asso 750 M (for Macchi) but was also commonly referred to as the Asso 2-800. The “2” designation was most likely applied because the engine was a “second generation” and differed greatly from the original Asso 750 design.

The single-speed supercharger on the Asso 750 RC35 is illustrated in this rear view. Note the relocated and new mounting point for the water pump. The supercharger forced-fed air to the engine’s six carburetors.

The Asso 2-800 had a bore of 5.91 in (150 mm), a stroke of 7.09 in (180 mm), and a total displacement of 3,434 cu in (57.3 L). The engine used new crossflow cylinder heads and a new crankcase. The cylinder heads had intake ports on one side and exhaust ports on the other. Air intakes for the engine were positioned behind the M.67’s spinner, with one intake on the left side for the left cylinder bank and two intakes on the right side for the center and right cylinder banks. Ducts delivered the air to special carburetors positioned between the cylinder banks. The modified engine also had a higher compression ratio and used special fuels. Under perfect conditions, the special Asso 2-800 engine produced up to 1,800 hp (1,342 kW), but it was rarely able to achieve that output. An output of 1,400 hp (1,044 kW) was more typical and still impressive. At speed, the Asso 2-800 in the M.67 reportedly made a roar like no other engine.

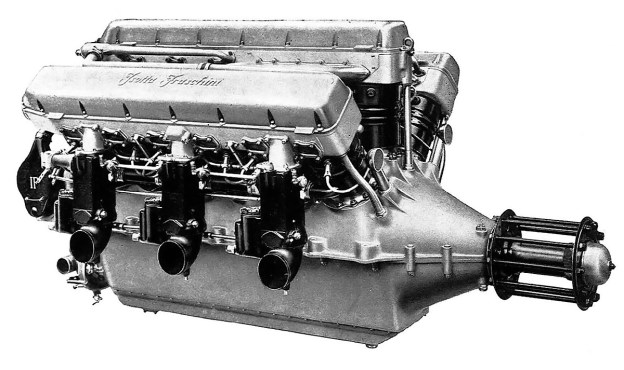

Isotta Fraschini made a commercial version of the larger engine, designated Asso 1000. With the same bore, stroke, and displacement as the Asso 2-800, the Asso 1000 is often cited as the engine powering the M.67. However, the Asso 1000 retained the same configuration and architecture as the Asso 750, except the Asso 1000 had a compression ratio of 5.3 to 1. Development of the Asso 1000 trailed slightly behind that of the Asso 750.

The direct drive Isotta Fraschini Asso 1000 produced 1,000 hp (746 kW) at 1,600 rpm and 1,100 hp (820 kW) at 1,800 rpm. The engine was 86 in (2.19 m) long, 42 in (1.06 m) wide, and 44 in (1.12 m) tall. The Asso 1000 weighed 1,764 lb (800 kg). Like with the original Asso 750, a gear reduction version was designed. This engine was sometimes designated as the Asso 1200 R. The gear reduction speeds available were .667 and .581. The Asso 1200 R produced 1,200 hp (895 kW) at 1,950 rpm and weighed 2,116 lb (960 kg).

The Isotta Fraschini Asso 1000 was very similar to the Asso 750. Note the intake manifolds between the cylinder banks, each taking the air/fuel mixture from one of the outer banks and feeding half of the center bank.

The Asso 750 and Asso 1000 engines were used in a variety of aircraft, but most of the aircraft were either prototypes or had a low production count. For the Asso 750, its most famous applications were the single engine Caproni Ca.111 reconnaissance aircraft (over 150 built) and the twin engine Savoia-Marchetti S.55 double-hulled flying boat. Over 200 S.55s were built, but only the S.55X variant was powered by the Asso 750. Twenty-five S.55X aircraft were built, and in 1933, 24 S.55X aircraft made a historic formation flight from Orbetello, Italy to Chicago, Illinois. The Asso 750 powered many aircraft to numerous payload and distance records. Six direct-drive Asso 1000 engines were used to power the Caproni Ca.90 bomber, which was the world’s largest landplane when it first flew in October 1929. The Ca.90 set six payload records on 22 February 1930.

Although not a complete success in aircraft, the Asso 1000 found its way into marine use as the Isotta Fraschini ASM 180, 181, 183 and 184 engines. ASM was originally written as “As M” and stood for Asso Marini (Ace Marine). The marine engines had water-cooled exhaust pipes and a reversing gearbox coupled to the propeller shaft. The Isotta Fraschini marine engines were used in torpedo boats before, during, and after World War II by Italy, Finland, Sweden, and Britain. Some of the engines and boats remained in service into the mid-1960s.

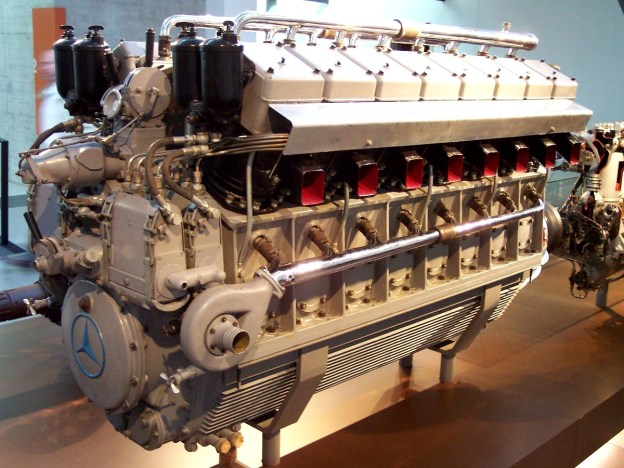

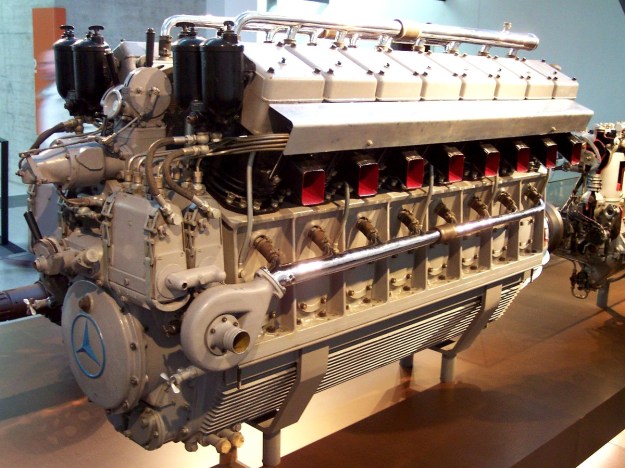

The Isotta Fraschini ASM 184 engine with its large, water-cooled exhaust manifolds and drive gearbox. Note that the center bank only has its rear (left) cylinders feeding into the visible exhaust manifold. One of the two centrifugal superchargers can be seen at the rear of the engine. The engine is on display at the Museo Nicolis in Villafranca di Verona. (Stefano Pasini image)

The ASM 180 and 181 were developed around 1933, and produced 900 hp (671 kW) at 1,800 rpm. Refinement of the ASM 181 led to the ASM 183, which produced 1,150 hp (858 kW) at 2,000 rpm. Development of the ASM 184 started around 1940; it was a version of the ASM 183 that featured twin centrifugal superchargers mounted to the rear of the engine. The ASM 184 engine produced 1,500 hp (1,119 kW) at 2,000 rpm. Around 1950, production of the ASM 184 was continued by Costruzione Revisione Motori (CRM) as the CRM 184. In the mid-1950s, the engine was modified with fuel injection into the supercharger compressors and became the CRM 185. The CRM 185 produced 1,800 hp (1,342 kW) at 2,200 rpm.

CRM continued development of the W-18 platform and created a diesel version of the engine. Designated 18 D, the engine retained the same bore, stroke, and basic configuration as the Asso 1000 and earlier ASM engines. However, the 18 D was made of cast iron, had revised cylinder heads, and had a compression ratio of 14 to 1. The revised cylinder head was much taller and incorporated extra space between the valve springs and the valve heads. The valve stems were elongated, and a pre-combustion chamber was positioned between the valve stems and occupied the extra space in the head. Some versions of the engine have a fuel injection pump consisting of three six-cylinder distributors driven from the rear of the engine, while other versions have a common rail fuel system.

Four CRM 18 D engines, which can trace their heritage back to the Asso 1000. The three engines on the left use mechanical fuel injection with three distribution pumps. The engine on the right has a common fuel rail. Note the three turbochargers at the front of each engine. (CRM Motori image)

The exhaust gases for each bank were collected and fed through a turbocharger at the front of the engine (some models had just two turbochargers). Pressurized air from the turbochargers passed through an aftercooler and was then fed into two induction manifolds. Each of the manifolds had three outlets. The front and rear outlets were connected to the outer cylinder bank, and the middle outlet was connected to the center bank. For the center bank, induction air for the rear three cylinders was provided by the left manifold, and the front three cylinder received their air from the right manifold.

Various versions of the 18 D were designed, the most powerful being the 18 D BR3-B. The BR3-B had a maximum output of 2,367 hp (1,765 kW) at 2,300 rpm and a continuous output of 2,052 hp (1,530 kW) at 2,180 rpm. The engine had a specific fuel consumption of .365 lb/hp/hr (222 g/kW/h). The BR3-B was 96 in (2.45 m) long, 54 in (1.37 m) wide, 57 in (1.44 m) tall, and weighed 4,740 lb (2,150 kg) without the drive gearbox. CRM, now known as CRM Motori Marini, continues to market 18 D engines.

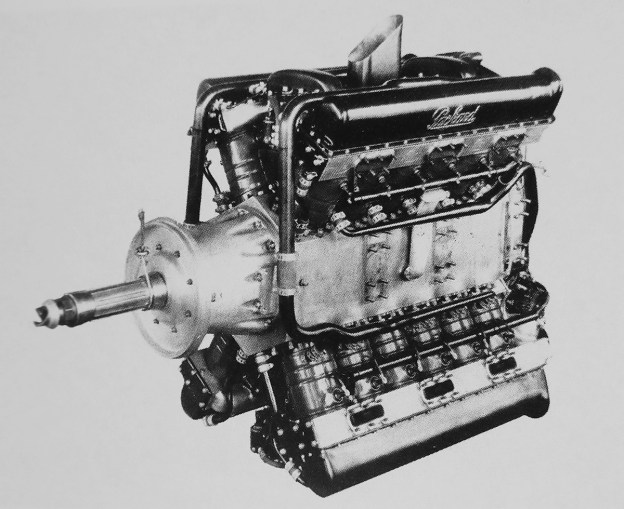

Other than having a W-18 layout, the Isotta Fraschini L.180 did not share much in common with the Asso 750 or 1000. However, the two-outlet supercharger suggests a similar induction system to the earlier engines. Note the gear reduction’s hollow propeller shaft and the mounts for a cannon atop the engine.

In the late 1930s, Isotta Fraschini revived the W-18 layout with an entirely new aircraft engine known as the Asso L.180 (or military designation L.180 IRCC45). The Asso L.180 was an inverted W-18 (sometimes referred to as an M-18) that featured supercharging and a propeller gear reduction. The engine’s layout and construction were similar to that of the earlier W-18 engines. One source states the cylinder banks were spaced at 45 degrees. With nine power pulses for each crankshaft revolution, this is off from the ideal of having cylinders fire at 40-degree intervals (like the earlier W-18 engines) and may be a misprint. The crankshaft was supported by seven main bearings in a one-piece aluminum crankcase. The spur gear reduction turned at .66 crankshaft speed and had a hollow propeller shaft to allow an engine-mounted cannon to fire through the propeller hub. The single-speed supercharger turned at 10 times crankshaft speed.

The Isotta Fraschini L.180 had a 5.75 in (146 mm) bore and a 6.30 in (160 mm) stroke. The engine displaced 2,942 cu in (48.2 L) and had a compression ratio of 6.4 to 1. The L.180 had a takeoff rating of 1,500 hp (1,119 kW) at 2,360 rpm, a maximum output of 1,690 hp (1,260 kW) at 2,475 rpm at 14,764 ft (4,500 m), and a cruising output of 1,000 hp (746 kW) at 1,900 rpm at 14,764 ft (4,500 m). It is doubtful that the L.180 proceeded much beyond the mockup phase.

A number of Isotta Fraschini aircraft and marine engines are preserved in various museums and private collections. Some marine engines are still in operation, and the German tractor pulling group Team Twister uses a modified Isotta Fraschini W-18 engine in its Dabelju tractor.

The modified Isotta Fraschini W-18 in Team Twister’s Dabelju. The engine’s heads have been modified to have individual intake and exhaust ports. These crossflow heads are similar in concept to the heads used on the Macchi M.67’s engine. (screenshot of Johannes Meuleners Youtube video)

Sources:

– Isotta Fraschini Aviation (undated catalog, circa 1930)

– Isotta Fraschini Aviation (1929)

– Isotta Fraschini Aviazione (undated catalog, circa 1931)

– Istruzioni per l’uso del motore Isotta-Fraschini Tipo Asso 750 (1931)

– Istruzioni per l’uso del motore Isotta-Fraschini Tipo Asso 750 R (1934)

– Istruzioni per l’uso del motore Isotta-Fraschini Tipo Asso 750 RC 35 (1936)

– Istruzioni per l’uso del motore Isotta-Fraschini Tipo Asso 1000 (1929)

– Aeronuatica Militare Museo Storico Catalogo Motori by Oscar Marchi (1980)

– Aircraft Engines of the World 1941 by Paul H. Wilkinson (1941)

– Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft 1931 by C. G. Grey (1931)

– https://www.t38.se/marinens-motortyper-i-mtb/

– http://www.crmmotori.it/interna.asp?tema=16