By William Pearce

In occupied France during World War II, the state-run manufacturer Arsenal de l’Aéronautique (Arsenal) was tasked with building the German Junkers Jumo 213 engine. The Jumo 213 was a liquid-cooled, inverted V-12 engine that displaced 2,135 cu in (35.0 L) and produced 1,750 hp at 3,250 rpm. After the war, Arsenal continued to develop the Jumo 213 and manufactured a 2,300 hp variant as the Arsenal 12H.

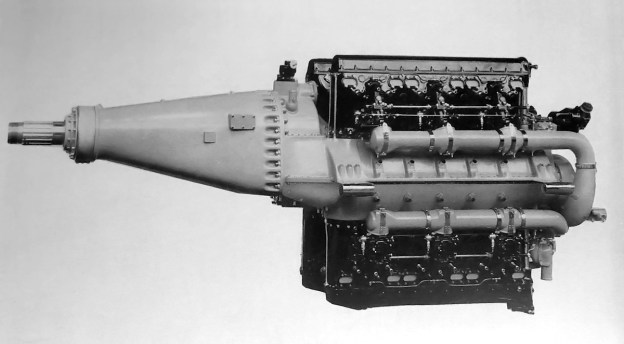

The Arsenal 24H was a 4,000 hp (2,983 kW), 24-cylinder engine that utilized many components originally designed for the Junkers Jumo 213 V-12. Note the centerline location of the single rotation propeller shaft.

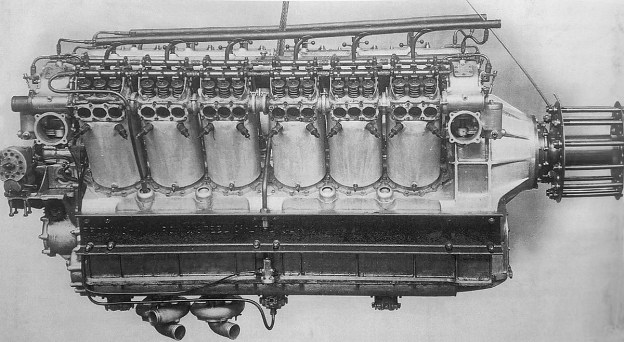

During the war, Junkers contemplated building the Jumo 212, which was an H-24 engine utilizing many Jumo 213 components. While the Jumo 212 was not built, it was designed along the same lines as the Hispano-Suiza 24Y and 24Z engines. It is not known if Arsenal was inspired by the Jumo 212 or the Hispano-Suiza H-24 engines, but they created their own H-24 engine based on parts from the Arsenal 12H (which was originally based on the Jumo 213). Arsenal’s 24-cylinder engine was known as the 24H.

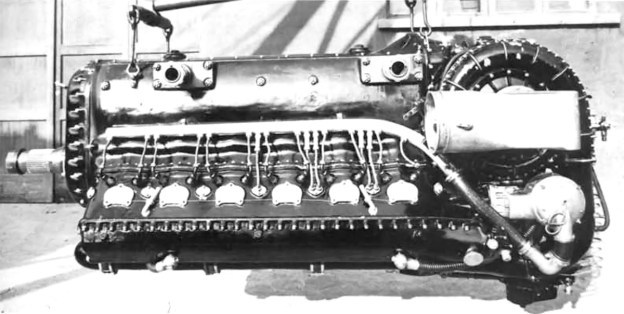

The Arsenal 24H was a vertical H engine with two cylinder banks mounted above the crankcase and two cylinder banks below. The two-piece aluminum crankcase was split vertically at its center. Covers on each side of the crankcase allowed access to the engine’s internals. While the cylinder blocks of the 12H were cast integral with its crankcase, the 24H used aluminum cylinder blocks that were separate. The detachable aluminum cylinder head featured two intake valves and one exhaust valve per cylinder. The valves for each cylinder bank were actuated by a single overhead camshaft driven by a vertical shaft at the rear of the engine.

Unlike the Jumo 213, the cylinder blocks of the 24H were detachable and not cast integral with the crankcase. Note the magnetos mounted atop the gear reduction housing. The fuel injection pumps are just visible above the top valve cover and and below the bottom valve cover.

Inside the crankcase were two crankshafts with enough horizontal separation to allow a shaft to pass between them. This feature would allow engines to be coupled in tandem. Each crankshaft served an upper and lower cylinder bank pair. The crankshafts had six throws and were supported by seven main bearings. Pistons with a compression ratio of 6.5 to 1 were attached to the crankshafts by fork-and-blade connecting rods.

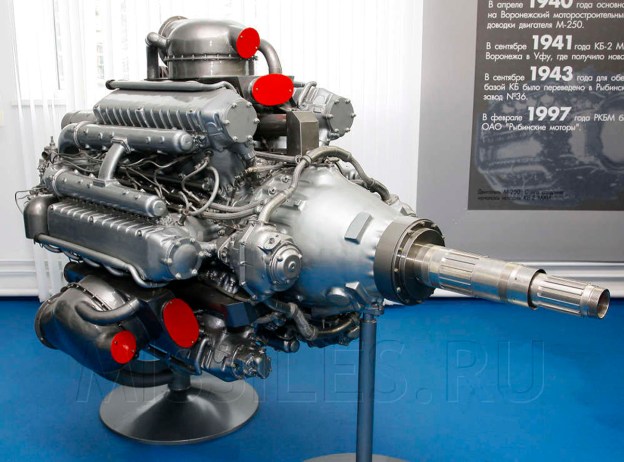

Two single-stage, two-speed superchargers were at the rear of the engine and driven by a cross-shaft from the engine’s accessory section. The superchargers had automatic boost and speed control with a low speed of 6.90 times crankshaft speed and a high speed of 9.41 times crankshaft speed. The left supercharger supplied air to the upper cylinder banks, and the right supercharger supplied air to the lower cylinder banks. The intake manifolds incorporated an aftercooler and were situated between their respective cylinder banks. A fuel injection pump was positioned between the cylinder banks and above the intake manifold. The 24H engine also utilized water injection.

On the 24H, the left supercharger fed air to the upper cylinder banks, and the right supercharger fed air to the lower cylinder banks. Note the large engine mounts on the side of the crankcase.

Each cylinder had two spark plugs which were positioned between the two intake valves and the single exhaust valve. The spark plugs were fired by two magnetos positioned at the front of the engine and above the propeller gear reduction housing. The propeller shaft was located on the engine’s centerline and incorporated a .4165 to 1 gear reduction. Although a contra-rotating gear reduction was designed, it is unclear if the unit was ever built, as all available images of the 24H show a single rotation propeller. The 24H and 12H shared cylinder heads, valve trains, most internal components, and many accessories, such as superchargers, fuel pumps, and magnetos.

The Arsenal 24H had a 5.91 in (150 mm) bore and a 6.50 in (165 mm) stroke. The engine’s total displacement was 4,270 cu in (69.98 L). With water injection and over-boosted at 11.0 psi (.76 bar), the 24H produced 4,000 hp (2,983 kW) at 3,250 rpm for takeoff. Without water injection, the 24H produced 3,500 hp (2,610 kW) at 3,250 rpm with 7.8 psi (.54 bar) of boost. The engine’s normal rating with low-speed supercharging was 3,200 hp (2,386 kW) at 3,000 rpm at 7,218 ft (2,200 m). With high-speed supercharging, the 24H had a normal rating of 3,000 hp (2,227 kW) at 3,000 rpm at 18,373 ft (5,600 m). The engine’s cruising power at 2,400 rpm was 2,200 hp (1,641 kW) at 9,843 ft (3,000 m) with low-speed supercharging and 2,000 hp (1,491 kW) at 17,060 ft (5,200 m) with high-speed supercharging. The 24H had a specific fuel consumption of .44 lb/hp/h (268 g/kW/h). The engine was 9.91 ft (3.02 m) long, 3.94 ft (1.20 m) wide, 4.92 ft (1.50 m) tall, and weighed 4,079 lb (1,850 kg).

Two 24H engines were installed in the inner positions on a Sud-Est SE 161 Languedoc. The tight cowling cannot hide the size of the large the 24H engine. Note the large radiator housing behind the engine. The lower exhaust row of the second 24H engine can be seen on the left side of the photo.

Detail design work of the 24H started in December 1945. By April 1946, the crankcase casting had been made and delivered to Arsenal. The engine was assembled in Arsenal’s factory in Châtillon (near Paris), France and was first run in May 1946. In November 1946, the 24H was exhibited at the Salon de l’Aéronautique (Air Show) in Paris. Issues with the Hispano-Suiza 24Z resulted in the Arsenal 24H being selected for the SNCASE (Sud-Est) SE 580 fighter. However, the SE 580 project was abandoned in 1947, and it does not appear that an Arsenal engine was ever installed. At least three 24H prototypes were built and run for a total of over 1,600 hours. The engine’s predicted performance of 4,000 hp (2,983 kW) was achieved on the test stand.

For flight testing, two 24H engines replaced the inner Pratt & Whitney R-1830 engines on a SNCASE (Sud-Est) SE 161/P7 Languedoc four-engine airliner. The engines were fitted with 10.5 ft (3.2m) diameter, metal, fully adjustable, five-blade propellers built by Ratier. The SE 161/P7 Languedoc with its 24H engines was flown for the first time in 1948. The engines performed well, but the relatively small propellers could not convert all of the 24H’s 4,000 hp (2,983 kW) to thrust. By the time the 24H had flown, the era of large piston aircraft engines was near its end. While the 24H was proposed for a few transports and flying boats (including eight engines used in the Latécorère Laté 182 and 184), new aircraft being built were designed with jet engines. There was no longer a need for a 4,000 hp (2,983 kW) engine, and the 24H was cancelled in 1950.

The SE 161 Languedoc appearing in a semi-abandoned state. One of the 24H engines has been removed, but exhaust stains are still present behind the remaining engine. Perhaps the aircraft was just used for ground runs when this photo was taken. Note the German aircraft in the background.

Arsenal was experienced with pairing engines in tandem to drive coaxial contra-rotating propellers, and they applied the concept to the 24H engine. Arsenal had developed a drive system for the Arsenal VB 10 fighter using a Vernisse or homocinetic coupling to join sections of the rear engine’s propeller shaft. This coupling incorporated flexibly-mounted ball joints to accommodate deflection and vibration of the propeller shaft. For the 24H Tandem engine, the propeller shaft of the rear engine passed through the crankcase, between the crankshafts, and extended through the propeller shaft of the front engine. The rear engine drove the front propeller of the coaxial contra-rotating unit, while the front engine drove the rear propeller. The Arsenal 24H Tandem displaced 8,541 cu in (139.96 L) and had a takeoff rating of 7,200 hp (5,369 kW), with some sources stating 8,000 hp (5,966 kW). The engine’s normal rating was 6,000 hp (4,474 kW) at 3,000 rpm. With a 39 in (1.0 m) shaft between the engine sections, the Tandem 24H weighed 9,039 lb (4,100 kg). Some sources claim that a 24H Tandem was constructed and run. The engine was considered for a few aircraft, including four 24H Tandem engines used in the Sud-Est 1200 flying boat. Cancellation of the 24H prevented any further development of the Tandem engine.

The 8,000 hp (5,966 kw) Arsenal 24H Tandem held some potential in a world of large transport aircraft and no jet engines. Fortunately for aviation, the jet engine proved to be both viable and revolutionary.

Sources:

– Les Moteurs a Pistons Aeronautiques Francais Tome 2 by Alfred Bodemer and Robert Laugier (1987)

– Jane’s All the Worlds Aircraft 1949-1950 by Leonard Bridgman (1949)

– Aircraft Engines of the World 1951 by Paul H. Wilkinson (1951)

– Junkers Flugtriebwerke by Reinhard Müller (2006)

– Les Avions de Combat Francais 1944-1960 I – Chasse-Assaut by Jean Cuny (1988)

– Latécorère: Les avions et hydravions by Jean Cuny (1992)

– World Encyclopedia of Aero Engines by Bill Gunston (2007)