By William Pearce

Ettore Bugatti was born in Milan, Italy on 15 September 1881. In 1909, he founded his own automobile company in Molsheim, in the Alsace region. The Alsace region was controlled by the German Empire until 1919, when control returned to France. The Bugatti race cars were incredibly successful in the 1920s and 1930s, collectively wining over 2,000 races. During that time period, Bugatti enjoyed seeing the small machines that bore his name defeat the larger and more powerful machines of his major rivals: the German vehicles from Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union.

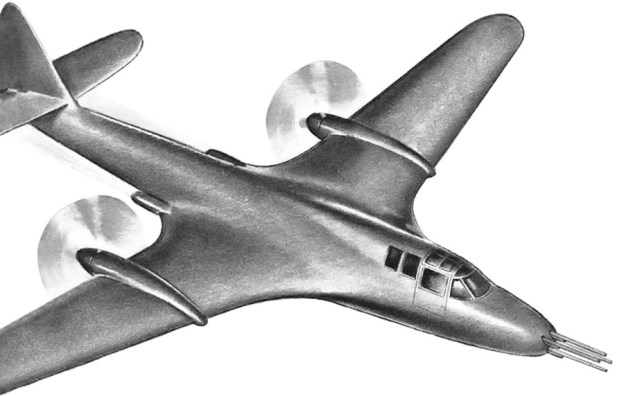

In 1936, Bugatti began to consider the possibility of building an aircraft around two straight eight-cylinder Bugatti T50B (Type 50B) engines, very similar to the engines that powered the Bugatti Grand Prix race cars. This aircraft would be used to make attempts on several speed records, most importantly, the 3 km world landplane speed record, then held by Howard Hughes in the Hughes H-1 Racer at 352.389 mph (567.115 km/h). Bugatti turned to Louis de Monge, a Belgian engineer, to help design the aircraft, known as the Bugatti Model 100P.

Bugatti 100P general arrangement drawing based off the original drawings by Louis de Monge. Note the arrangement of the power and cooling systems.

Before construction of the Bugatti 100P began, Germany demonstrated what if felt was its aerial superiority by setting a new 3 km world landplane speed record at 379.63 mph (610.95 km/h) in a Messerschmitt Bf 109 (V13) on 11 November 1937. Bugatti disliked Nazi-Germany and was very interested in beating their record. Bugatti and de Monge continued to develop the 100P for an attempt to capture the 3 km record from Germany.

The Bugatti 100P was one of the most beautiful aircraft ever built. With the exception of engine exhaust ports, the 25 ft 5 in (7.75 m) fuselage was completely smooth. The aircraft employed wood monocouque “sandwich” construction in which layers of balsa wood were glued and carved to achieve the desired aerodynamic shape. Hardwood rails and supports were set into the balsa wood to take concentrated loads at stress points, like engine mounts and the canopy. The airframe was then covered with tulipwood strips, which were then sanded and filled. Finally, the aircraft was covered with linen and doped. The Bugatti 100P stood 7 ft 4 in (2.23 m) tall and weighed 3,086 lb (1,400 kg).

The 100P had a 27 ft (8.235 m), one-piece wing that was slightly forward-swept. The wing had a single box spar that ran through the fuselage. The wing was constructed in the same fashion as the fuselage and housed the fully retractable and enclosed main gear. The wing featured a multi-purpose, self-adjusting flap system (U.S. patent 2,279,615). Both the upper and lower flap surfaces automatically moved up or down to suit the speed of the aircraft and the power setting (manifold pressure) of the engines. At high manifold pressure and very low airspeed, the flaps set themselves to a takeoff position. At low airspeed and low power, the flaps dropped into landing position, and the landing gear was automatically lowered. In a dive, the flaps pivoted apart to form air brakes.

Image of the nearly complete Bugatti 100P still under construction in Paris. The cooling-air inlet in the butterfly tail can be easily seen.

The Bugatti tail surfaces consisted of two butterfly units and a ventral fin at 120-degree angles (French patent 852,599). They were constructed with the same wood “sandwich” method used on the fuselage and wing. The tip of the ventral fin incorporated a retractable tail skid. For cooling, air was scooped into ducts in the leading edges of the butterfly tail and ventral fin. The air was turned 180 degrees, flowed into a plenum chamber in the aft fuselage, and passed through a two section radiator (one section for each engine) located behind the rear engine. The now-heated air again turned 180 degrees and exited out the fuselage sides into a low pressure area behind the trailing edge of the wings. The high pressure at the intake and low pressure at the outlet created natural air circulation that required no fans or blowers (U.S. patent 2,268,183).

The two Bugatti T50B straight eight-cylinder engines were specially made for the 100P aircraft. The engine crankcases were made of magnesium to reduce weight, and each engine used a lightweight Roots-type supercharger feeding two downdraft carburetors. The T50B had a bore of 3.31 in (84 mm) and a stroke of 4.21 in (107 mm), giving a total displacement of 289 cu in (4.74 L). Twin-overhead camshafts actuated the two intake and two exhaust valves for each cylinder. The standard T50B race car engine produced 480 hp (358 kW) at 5,000 rpm. An output of 450 hp (336 kW) at 4,500 rpm is usually given for the 100P’s engines; however, de Monge stated the engines planned for the 100P were to produce 550 hp (410 kW) each. The engines were situated in tandem, behind the pilot. The front engine was canted to the right and drove a drive shaft that passed by the pilot’s right side. The rear engine was canted to the left and drove a drive shaft that passed by the pilot’s left side. The two shafts joined into a common reduction gearbox just beyond the pilot’s feet. The gearbox allowed each engine to drive a metal, two-blade, ground-adjustable Ratier propeller. Together, the two propeller sets made a coaxial contra-rotating unit. From the gearbox, the rear propeller shaft (driven by the front engine) was hollow, and the front shaft (driven by the rear engine) rotated inside it (U.S. patent 2,244,763).

Image of the two T50B engines in the Bugatti 100P while at the Ermeronville estate. Note the radiator at left , how the engines are canted within the fuselage, and how the exhaust ports on the front engine protrude through the fuselage.

Once the new design was finalized in 1938, construction of the 100P was begun at a high quality furniture factory in Paris. While construction proceeded, it was obvious that war would break out soon. France did not have any fighters that could match the performance of their German counterparts. The French Air Ministry felt the 100P could be developed into a light pursuit or reconnaissance fighter and awarded a contract to Bugatti in 1939. This fighter was to be equipped with at least one gun mounted in each wing, an oxygen system, and self-sealing fuel tanks. Most aspects of the fighter are unknown, but it is possible that it was larger than the 100P and incorporated 525 hp (391 kW) T50B engines installed side-by-side in the fuselage driving six-blade coaxial contra-rotating propellers with a 37-mm cannon firing through the propeller hub. Because of France’s surrender, the aircraft never progressed beyond the initial design phase.

The Bugatti 100P, finally in all its glory after being completely restored by the Experimental Aircraft Association. Note the fairing for the rear engine ‘s exhaust ports above the wing. (Hugh Conway Jr. image)

Bugatti’s contract included a bonus of 1 million francs if the 100P racer captured the world speed record which the Germans had raised to 463.919 mph (746.606 km/h) with a Heinkel He 100 (V8) on 30 March 1939 and raised again to 469.221 mph (755.138 km/h) with a Messerschmitt Me 209 (V1) on 26 April 1939. Bugatti and de Monge felt the 100P was capable of around 500 mph (800 km/h). In addition, a smaller version of the racer, known as the 110P, was planned; it featured a 5 ft (1.525 m) reduced wingspan of 22 ft (6.7 m). The 110P was to have the same engines as the 100P, but the top speed was estimated at 550 mph (885 km/h). However, other sources indicate these figures were very optimistic, and the expected performance was more around 400 mph (640 km/h) for the 100P and 475 mph (768 km/h) for the 110P.

The 100P was nearly complete when Germany invaded France. As the Germans closed in on Paris in June 1940, the Bugatti 100P and miscellaneous parts, presumably for the 110P, were removed from the furniture factory and loaded on a truck. The 100P was taken out into the country and hidden in a barn on Bugatti’s Ermeronville Castle estate 30 mi (50 km) northeast of Paris.

Bugatti 100P on display at the EAA AirVenture Museum in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. The cooling air exit slots on the left side of the aircraft can be seen on the wing trailing edge fillet. Also note the tail skid on the ventral fin.

Ettore Bugatti died on 21 August 1947 with the 100P still stashed away in Ermeronville. The aircraft was purchased by M. Serge Pozzoli in 1960 but remained in Ermeronville until 1970 when it was sold to Ray Jones, an expert Bugatti automobile restorer from the United States. Both Pozzoli and Jones offered the 100P to French museums but were turned down. Jones acquired the 100P with the intent to complete the aircraft; however, that goal could not be completed due to missing parts. Jones had the two Bugatti T50B engines removed from the airframe before everything was shipped to the United States. Dr. Peter Williamson purchased the airframe and moved it to Vintage Auto Restorations in Ridgefield, Connecticut in February 1971 to begin a lengthy restoration. Les and Don Lefferts worked on the project from 1975 to 1979. Louis de Monge was now living in the United States and assisted with some aspects of the restoration work before he passed away in 1977. In 1979, the unfinished 100P was donated to the Air Force Museum Foundation with the hope of having the restoration completed and the aircraft loaned to a museum for display. However, the aircraft sat until 1996 when it was donated to the Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA) in Oshkosh, Wisconsin and finally underwent a full restoration. The restored, but engineless, Bugatti 100P is currently on display at the EAA AirVenture Museum.

The original engines out of the Model 100P were reportedly not the final version of the engines intended for the actual speed record run. Both engines still exist and are installed in Bugatti automobiles. The front engine is installed in Ray Jones’ 1937 Type 59/50B R Grand Prix racer, and the rear engine is installed in Charles Dean’s 1935 Type 59/50B Grand Prix racer. Since January 2009, Scotty Wilson has led an international team, including Louis de Monge’s grand-nephew, Ladislas de Monge, to build a flying replica of the Bugatti 100P in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Piloted by Wilson, the Bugatti 100P replica flew for the first time on 19 August 2015. Tragically, Scotty Wilson was killed when the replica crashed during a test flight on 6 August 2016.

Bugatti 100P on display at the EAA AirVenture Museum in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Simply one of the most beautiful aircraft ever built.

Sources:

– The Bugatti 100P Record Plane by Jaap Horst (2013)

– World Speed Record Aircraft by Ferdinand Kasmann (1990)

– Airplane Racing by Don Berliner (2009)

– The Classic Twin-Cam Engine by Griffith Borgeson (1979/2002)

– http://www.bugattiaircraft.com/kalempa.htm by Alex Kalempa

– http://www.airventuremuseum.org/collection/aircraft/2Bugatti Model 100 Racer.asp

– http://www.airventuremuseum.org/collection/aircraft/2Bugatti Model 100 Racer Facts.asp

– http://morlock68.pagesperso-orange.fr/bugatti.htm

– http://bugatti100p.com/

– http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bugatti

– http://kfor.com/2016/08/06/historic-replica-airplane-the-bugatti-100p-crashes-near-burns-flat-pilot-and-designer-scotty-wilson-dies/