By William Pearce

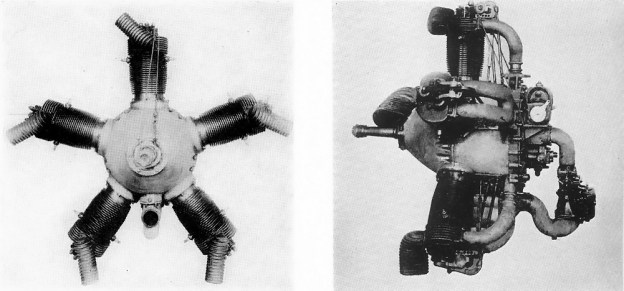

Albert (Al) S. Menasco got his start in the aircraft engine business in 1926 when he was tasked with settling the estate of his friend Art Smith. Before he passed, Smith had purchased 250 Salmson Z-9 water-cooled 9-cylinder radial engines. Waldo Waterman approached Menasco with an idea to convert the Salmson engines to air-cooling. Menasco ended up progressing on his own with the project and made further modifications to the Salmsons. Despite his best efforts, Menasco could not make the Menasco-Salmson B-2 engine reliable enough to pass the new Department of Commerce’s 50-hour test.

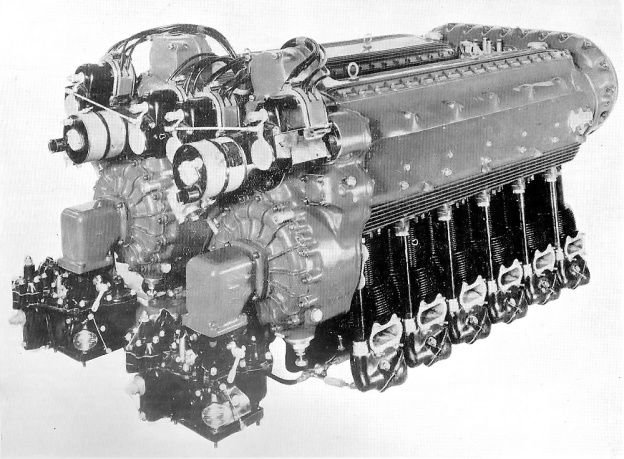

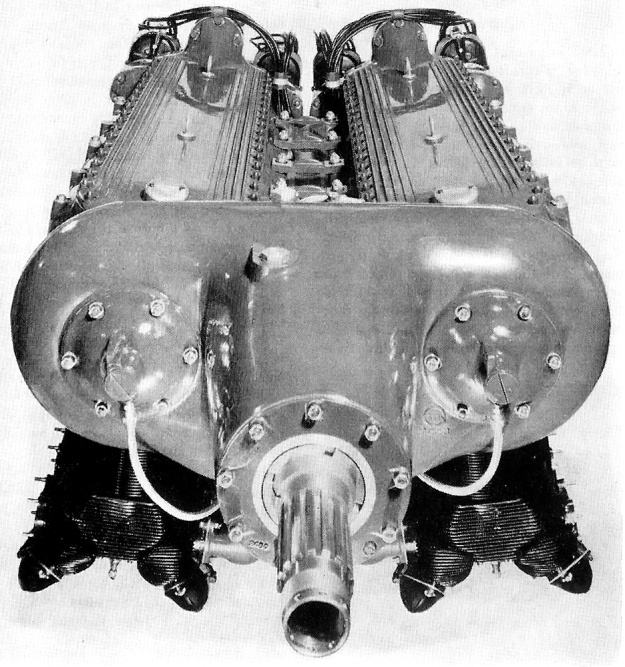

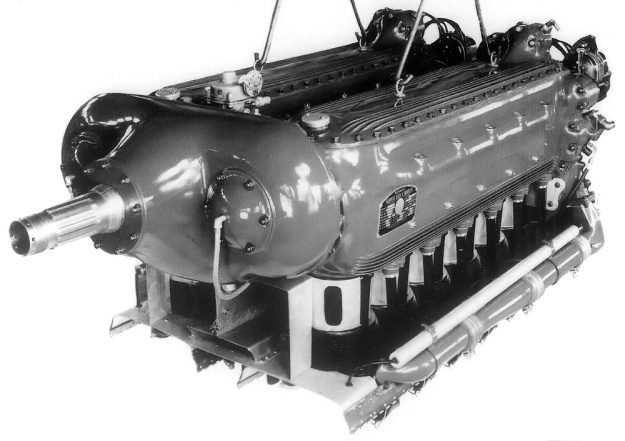

This front view of the Unitwin illustrates the slight contrary angle of the Buccaneer engine sections. Visible are the brackets that bolt the two crankcases together to make the Unitwin more rigid. Note the oil supply lines on each side of the gear case for spraying oil on the freewheeling clutches.

In 1928, Menasco found himself with a good shop and a good crew but no engine to manufacture. Jack Northrop was visiting Menasco one day and suggested he should build an inverted, in-line, air-cooled, four-cylinder aircraft engine. This was the start of the 90 hp (67 kW) four-cylinder Menasco Pirate engine and quickly led to the 160 hp (119 kW) six-cylinder Menasco Buccaneer in 1931. Remembering the troubles with the Salmson, Menasco designed these engines to run at 125% rated power for 100 hours straight. The Pirate and Buccaneer were very popular and very successful engines with air racers. Over years of continued development, the engines were supercharged and their output increased to 150 hp (112 kW) and 260 hp (194 kW) respectively.

In mid-1935, Robert Gross, Cyril Chappellet, and Hall Hibbard discussed with Menasco the possibility of coupling two six-cylinder Buccaneer engines together side-by-side to make an inverted U-12 engine. Gross, was the President of the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation, Chappellet its corporate secretary, and Hibbard its chief engineer. Menasco thought the Buccaneer could be developed to produce 350 hp (261 kW), giving the coupled engine 700 hp (522 kW). Through freewheeling (or overrunning) clutch mechanisms, the two engines would power a single propeller. If one engine were to fail, the other would be unaffected and continue to power the constant-speed propeller. The propeller’s pitch would change to compensate for the decrease in power. This arrangement would give twin-engine reliably without the drag of a conventional twin-engine installation or the asymmetric thrust during an engine failure. The men from Lockheed thought the engine would be well suited to power personal aircraft or small feeder aircraft for airline service.

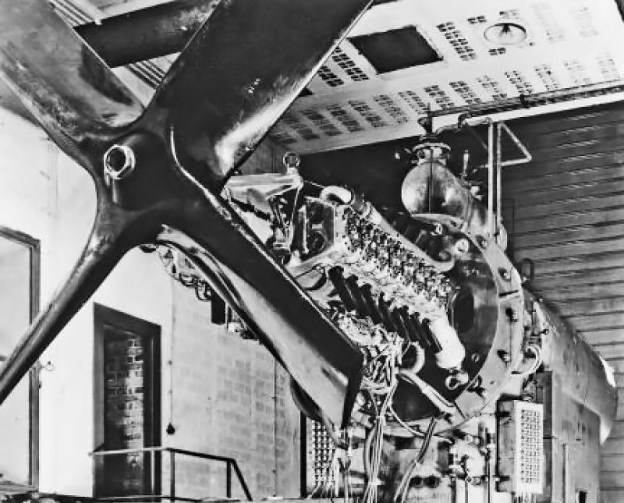

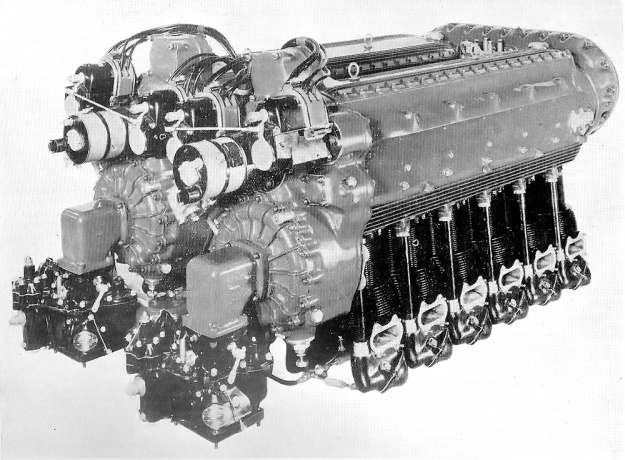

The Menasco Unitwin engine with the air-cooling baffles in-place. Note the intake manifold: on a standard Buccaneer engine, this manifold was on the opposite side. On the Unitwin, both engine sections had the intake manifold on the outside of the engine. Note the revised oil lines to the gear case compared with the previous image.

In 1936 and with Lockheed sponsorship, Menasco coupled two 90 hp Wright Gipsy four-cylinder engines to test the feasibility of a freewheeling gear case. This coupled engine endured 300 hours of tests and paved the way for the Menasco Unitwin. Lockheed formed a new subsidiary, the Vega Airplane Company (originally the AiRover Company), to manufacture an aircraft powered by the Unitwin. In addition, Lockheed explored the possibility of installing Unitwin engines in its Model 12 Electra Junior. By 1937, Vega had taken over the Unitwin project which was behind schedule. Issues were encountered with the Buccaneer engine being able to produce the desired 350 hp (261 kW) output. In addition, the Menasco Manufacturing Company was in poor financial health. Lockheed’s Gross and Chappellet personally invested in Menasco to keep the company going.

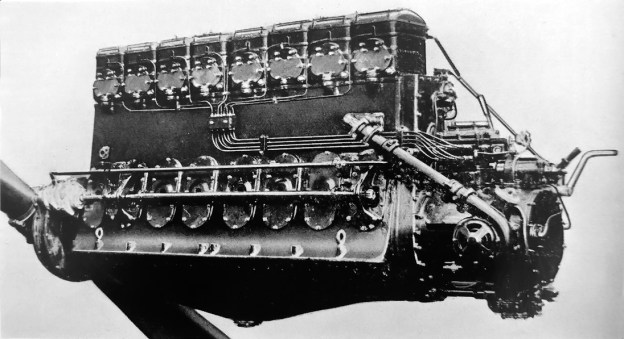

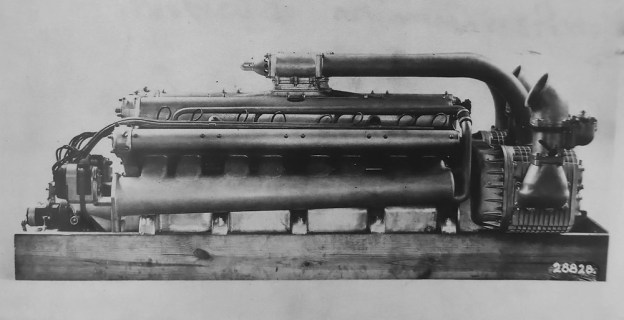

The Menasco 2-544 Unitwin was comprised of two 544 cu in (8.9 L) C6S-4 Super Buccaneer six-cylinder engines. The Buccaneer engines were positioned side-by-side and coupled together by a common gear case. Each engine was canted out 10-degrees from vertical. The gear case housed hydraulic freewheeling clutches that allowed the engines to be operated completely independent of each other. In addition, the rear of the gear case had provisions to run essential accessories, including the prop governor and an oil pump. The gear case had its own oil supply, independent from the engine sections. The engine sections were modified to rotate opposite the normal direction, and once through the gear case, rotation returned to normal for the use of a standard propeller. The gear case also incorporated a 0.667 (may have been 0.6375) propeller gear reduction.

Rear view of the Menasco Unitwin showing the separate superchargers, carburetors, magnetos, and starters.

Rigid supports connected the two Buccaneer crankcases together to utilize one engine mount. The two rows of cylinder shared baffles to direct the cooling air through their fins. Later in development, the intake and exhaust on the left engine section were reversed; this allowed the intake manifolds to travel along the outside of both engine sections and for the exhaust manifolds to be located in the middle, between the sections.

The inverted U-12 had a 4.75 in (121 mm) bore and a 5.125 in (130 mm) stroke. Total displacement was 1,090 cu in (17.9 L). Each cylinder had one intake and one exhaust valve actuated by pushrods. Two spark plugs per cylinder were fired by Scintilla magnetos, two on each engine section. The compression ratio was 5.5 to 1, and each engine section had its own supercharger. The engine produced 580 hp (433 kW) at 2,400 rpm and had a maximum output of 660 hp (492 kW) at 2,700 rpm. The Unitwin was 80.0 in (2.0 m) long, 38.0 in (1.0 m) wide, and 30.5 in (0.8 m) tall. The engine weighed 1,380 lb (626 kg).

Other Unitwin gear case and engine configurations were considered. One gear case design raised the propeller shaft above the engine. With a hollow propeller shaft, this would allow a machine gun or cannon to be mounted above the engine with its barrel projecting through the propeller shaft. This design was intended for military use, but it is unlikely that it was ever built. A different engine configuration arranged the cylinders horizontally, to create a “flat” engine for installation buried in an aircraft’s wing. This engine configuration was never built.

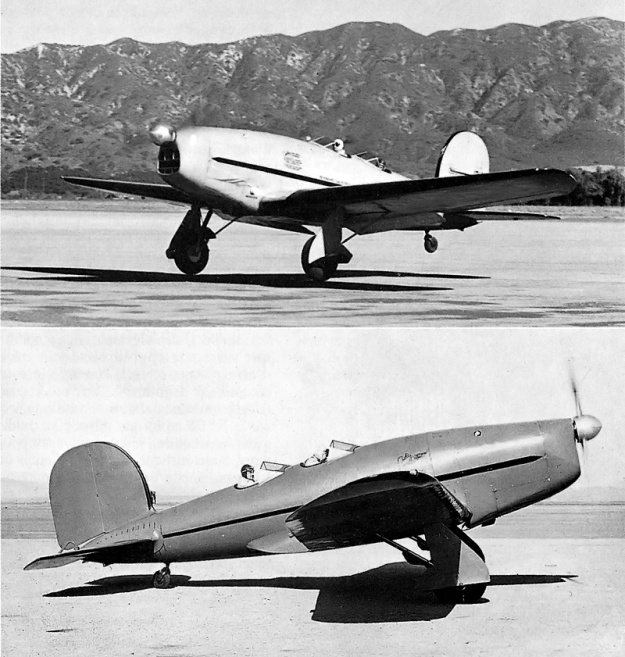

While the Unitwin was undergoing stringent bench tests to prove its reliability, Vega (AiRover) assembled a Lockheed Altair 8G (registered NX18149) from spare parts to serve as a flying testbed for the engine. This aircraft was the AiRover/Vega Model 1 and was also called the Flying Test Stand. The Unitwin-powered Altair first flew on 29 June 1938. In this aircraft, the Unitwin was put through its paces. One engine section would run at a steady power while the other was throttled quickly between full open and closed. With one engine’s throttle sealed closed, the Altair took off and climbed to 12,000 ft (3,658 m) without aircraft stability or engine cooling issues. However, the Menasco Manufacturing Company’s financial issues continued to worsen, and Gross and Chappellet essentially took over the company. This resulted in Al Menasco leaving the company in June 1938.

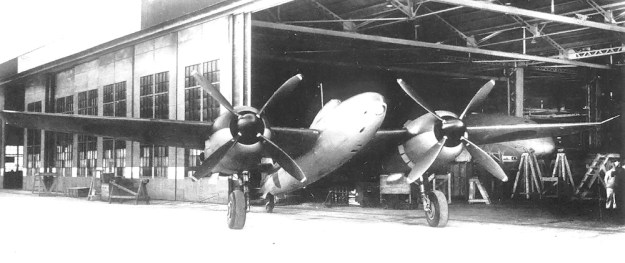

Encouraged by the results of the Unitwin in the Altair, Vega built a five to six place aircraft around the engine. Vega president, Mac Short, oversaw the design of this aircraft, known as the Vega Model 2 Starliner (registered as NX21725). The Starliner was meant to appeal as a feeder airliner and an executive and personal transport aircraft. Its first flight, on 22 April 1939, ended in an emergency landing when the propeller slipped into fine pitch. The pilot (Vern Dorrell) and observer (J. B. Kendrick) were uninjured, and the Starliner escaped with only minor damage.

The two-piece windscreen and twin tails of the Vega Starliner gave it a similar appearance to contemporary Lockheed transports.

The aircraft was originally built with twin tails. While it was being repaired, a single, conventional tail replaced the twin fins, and the rear of the fuselage was modified. The Starliner was soon back in the air but was later damaged again when the nose gear would not extend for landing. The aircraft was repaired again, but Vega was becoming increasingly occupied with government contracts. In addition, Vega realized the Unitwin would never be able to produce 700 hp (522 kW) and that the Starliner was too small for feeder line service. One aircraft was ordered by Mid-Continent Airlines, but this order was later cancelled.

After amassing 85 hours of flight time, Starliner development was discontinued. The airframe was sold off as a Hollywood prop. Although the Unitwin engine operated without issues and performed as designed, it had no prospects beyond the Starliner. Menasco Manufacturing Company, like Vega, was receiving a flood of government contracts; therefore, Unitwin development was halted in 1940. There are no known surviving examples of this engine.

The Menasco Unitwin-powered Vega Starliner with a single tail. Note the updated paint job with “Starliner” on the engine cowl.

Sources:

– “Unitwin Power Plant” by Mac Short, Aero Digest (February 1939)

– Aerosphere 1939 by Glenn Angle (1940)

– Race With the Wind by Birch Matthews (2001)

– Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft 1940 by C. G. Grey and Leonard Bridgman

– Multiple Motor Drive for Aircraft Propellers US patent 2,284,473 by Albert S. Menasco and Hall L. Hibbard (granted 26 May 1942)

– Multiple Motor Drive US patent 2,180,599 by Albert S. Menasco (granted 21 November 1939)

– Lockheed Aircraft since 1913 by Rene J. Francillon (1982/1987)

– The Menasco Story by Ralph J. Schmidt (1994)

– “Menasco Aircraft Engines and their Air Racing Heritage, Part 1” by Larry M. Rinek, Torque Meter Vol. 2 No. 4 (Fall 2003)

– Waldo: Pioneer Aviator by Waldo Dean Waterman with Jack Carpenter (1988)