By William Pearce

Léon Levavasseur was one of those rare geniuses of early aviation who designed and built engines as well as aircraft. In the early 1900s, Levavasseur gave up his career as an electrical engineer to focus on aviation. He needed funding to pursue his interests, so in August (some say July) 1902, Levavasseur approached industrialist and fellow Frenchman Jules Gastambide. Levavasseur had impressed and then befriended Gastambide when he repaired generators at one of Gastambide’s power plants. At the July meeting, Levavasseur outlined his plans for an aircraft of his design to be powered by a new engine that he was also designing. Levavasseur suggested the new enterprise should be named Antoinette, after Gastambide’s young daughter. Gastambide was interested but thought the engine should be built first, as no aircraft had yet flown. Levavasseur was agreeable, and with financial backing secured, he set to work on the new engine.

An Antoinette mechanic (left), Hubert Latham (middle), and Léon Levavasseur (right) with an Antoinette IV aircraft powered by a 50 hp (37 kW) Antoinette V-8 at Camp de Châlons in early June 1909. At the event, Latham flew continuously for 1:07:37, setting a French endurance record. Note the condenser under the aircraft’s wing.

Levavasseur quickly returned to Puteaux (near Paris), France, and set up a shop to work on the new engine. On 28 August 1902, Levavasseur applied for a secret patent on his engine, which consisted of eight cylinders laid out in a Vee pattern, forming two banks of four cylinders. This patent application became public on 28 August 1903 and was granted French patent no 399,068 on 30 September 1904.

From 1902 through 1910, Levavasseur produced several different Antoinette engines, but they all used the same basic layout. Technically, the first time the “Antoinette” name was applied during the Levavasseur-Gastambide partnership was in 1905 when a series of boats were so named. It would not be until 1906 that the Société Anonyme Antoinette was officially incorporated.

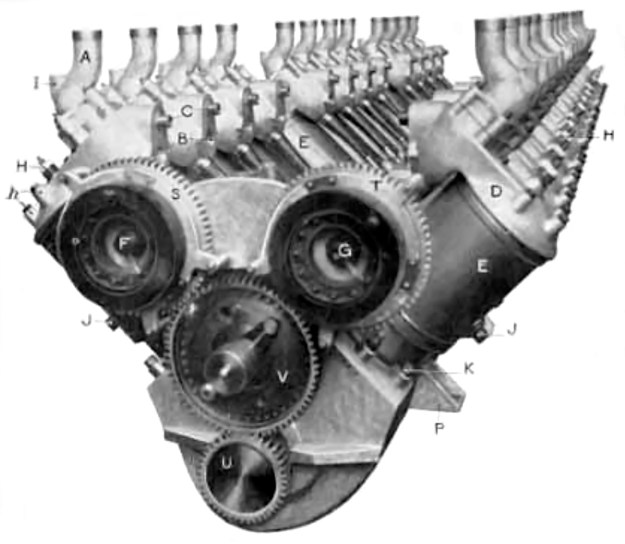

All of Levavasseur’s engines consisted of individual, water-cooled cylinders arranged in a 90 degree Vee on an aluminum crankcase. The cylinders were staggered on the crankcase to facilitate the use of side-by-side connecting rods. With this arrangement, the connecting rods for each left and right cylinder pair attached to the crankshaft on the same crankpin. This allowed the engine to be much shorter than if each connecting rod had its own crankpin. The connecting rods were of a tubular design, and the pistons were made from cast iron.

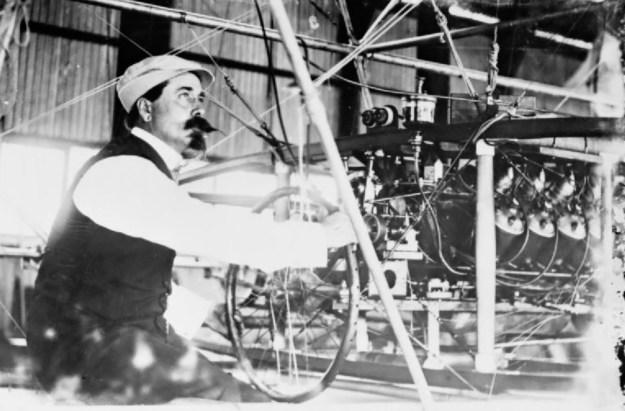

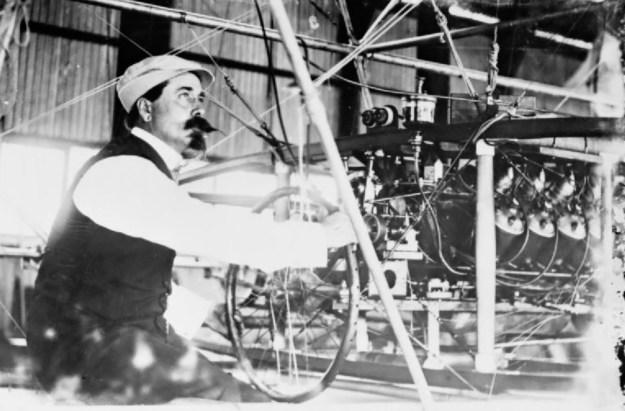

A 1907 image of Samuel Cody with a 50 hp (37 kW) Antoinette V-8 in the framework of the “Nulli Secundus,” Britain’s first airship.

Each cylinder had one intake and one exhaust valve positioned on the Vee side of the cylinder. The intake valve was situated above the exhaust valve, creating an “F-head” or “Intake Over Exhaust” (IOE) cylinder head. The intake valve was atmospheric (automatic)—drawn open by the vacuum created in the cylinder as the piston moved down. The exhaust valve was actuated by a pushrod driven by the camshaft located in the Vee of the engine. The top of the cylinder’s combustion chamber was hemispherical, with a single spark plug positioned at its center.

The Antoinette engines used a primitive type of direct fuel injection. A belt-driven fuel pump at the rear of the engine fed fuel into a small reservoir (injector) located above each intake valve. When the intake valve opened, the suction that drew in air also pulled in fuel from the reservoir via a narrow, capillary passageway .008 in (.2 mm) in diameter. By manipulating the fuel pump, the pilot could exert a certain degree of fuel flow regulation. However, the system had some issues, and Antoinette engines had difficulty running at low rpm. In addition, the small passageways in the “injectors” easily became clogged by impurities in the fuel. These complications led some Antoinette operators to convert the engine to a carbureted induction system.

To cool a normal Antoinette engine, a belt-driven water pump at the rear of the engine provided water to an inlet at the base of each cylinder on the outer side of the engine. The water then passed up through the water jacket and along the cylinder barrel. The water exited the top of the cylinder on the Vee side of the engine, where it flowed into a common manifold for each cylinder bank. The water was then taken to a radiator or to a reservoir tank, as engine cooling was not critical on very short flights.

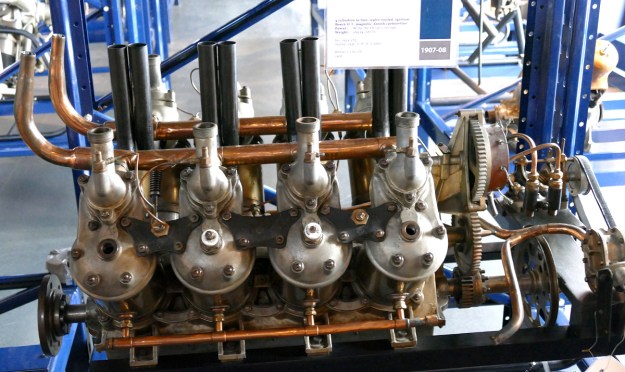

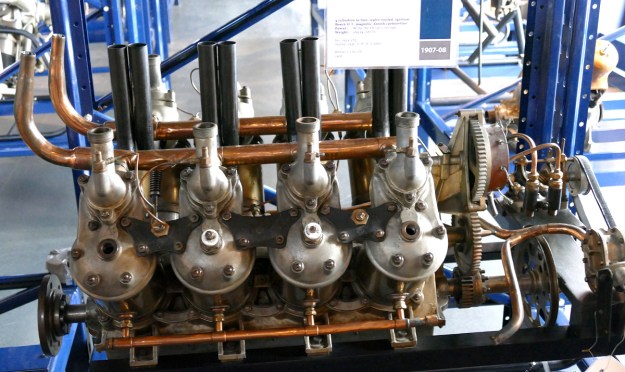

This 50 hp (37 kW) Antoinette V-8 engine is on display at the Science Museum in London and may have been used by Cody in 1908 for the first flight in Britain. Note the aluminum cylinder heads, brass water jackets, and copper water manifolds. The fuel distributor can be seen on each vertical intake pipe. (Warbird Tails image)

For lubrication, oil was taken from the crankcase and pumped through a pipe inside the crankcase, just above the camshaft. The pipe ran the length of the engine and was pierced with numerous small holes. Oil sprayed from the pipe, lubricating all of the engine’s internal components. Any components not in direct contact with an oil spray were lubricated by the oil mist created inside the crankcase.

Some (but not all) of the Antoinette engines had the ability to reverse their running. This was particularly helpful for braking and maneuvering in dirigibles. The camshaft was normally locked into its driving gear at the rear of the engine. With the engine stopped, the camshaft could be unlocked, rotated 90 degrees, and locked into a second position in its driving gear. One position was for normal (counter-clockwise) rotation, and the other was for reverse rotation (clockwise).

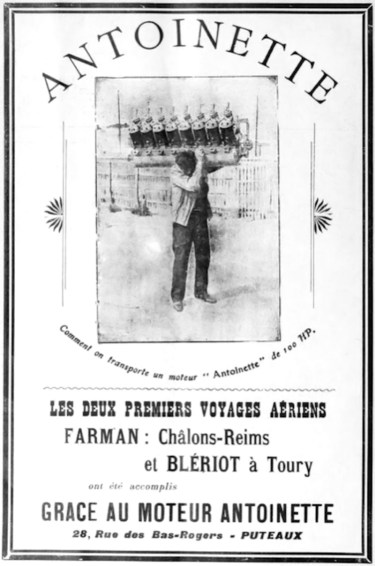

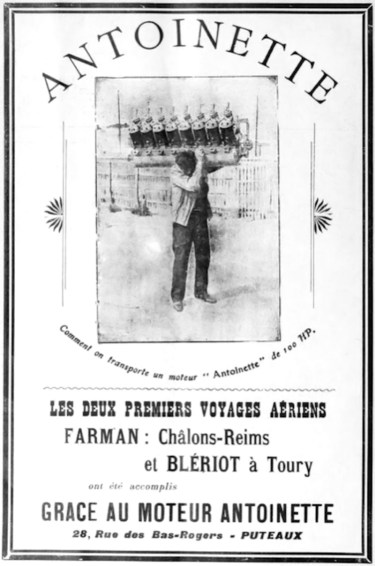

Antoinette engine ad circa 1907 illustrating the lightness of the 220 lb (100 kg), 100 hp (75 kw) V-16 engine.

Each Antoinette engine was made to the highest standards in a shop that boasted of tolerances down to .0004 in (.01 mm). Another feature of all Antoinette engines was that their components were engineered to be just strong enough for their individual tasks. By designing parts with operating stresses in mind, all extra material could be eliminated, resulting in complete engines that were much lighter than their contemporaries. This design philosophy also had a drawback: engine reliability could suffer because parts were more easily overstressed, resulting in a failure. Antoinette engines were relatively specialized, and when one was in need of repair, it had to be shipped back to the factory.

The early Antoinette engines used open cylinder barrels made from cast iron. An aluminum cylinder head was bolted to the barrel. Each cylinder had a spun brass water jacket shrink-fitted to the cylinder head. The engine’s spark plugs were fired by a battery-powered ignition coil distributor.

Levavasseur’s first engine was running by the end of 1902, but efforts to improve the engine were undertaken throughout 1903. The engine was a V-8 with a 5.12 in (130 mm) bore and stroke. The engine’s total displacement was 842 cu in (13.8 L), and it produced 80 hp (60 kW). Initially, the engine weighed 346 lb (157 kg), but refinements brought the weight down to 320 lb (145 kg).

An Antoinette V-16 engine possibly in storage at the Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace in Le Bourget, France. Note how the V-16 utilized all the same components as the V-8, with the exception of the crankcase, crankshaft, camshaft, and water manifolds. This engine has rather unusual exhaust stacks. (image source)

The 80 hp (60 kW) Levavasseur engine underwent a military test in March 1903 in which it produced 63 hp (50 kW). This output was derived by using a alternative power calculation method, and Levavasseur objected to the results. A little later, the engine was tested again, using another power calculation method. During this test, the engine registered an output of 82 hp (61 kW). The engine’s performance and Levavasseur’s ideas sufficiently impressed General Louis André, France’s Minister of War, who then provided 20,000 Francs of secret funds to Levavasseur for the construction of his airplane.

From July to September 1903, Levavasseur built his airplane in Villotran, France, which is why the aircraft became known as the Aéroplane de Villotran. The aircraft was powered by the 80 hp (60 kW) engine. Unfortunately, the aircraft proved incapable of flight. By 15 September 1903, Levavasseur had decided the aircraft was a failure; the engine was removed, and the aircraft was burned.

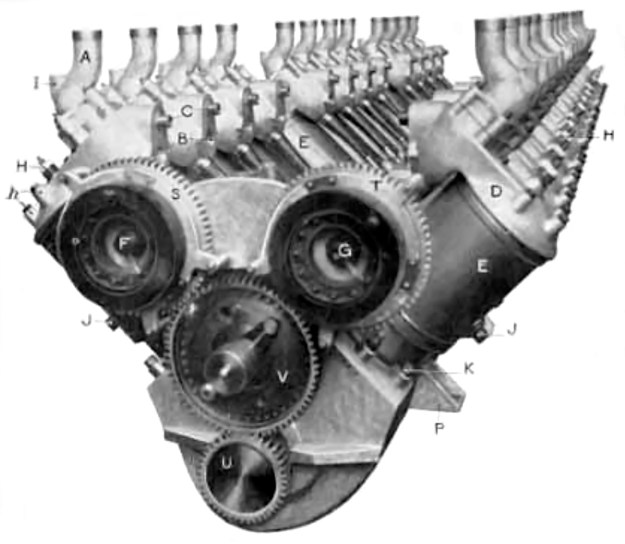

The 360 hp (268 kW) Antoinette V-24 marine engine of 1906. Unlike the V-16 engines, the V-24 appears to be comprised of V-8 engine sections. The engine is labeled as follows: A) air intake pipe; B) exhaust; C) cooling water outlet; D) aluminum cylinder head; E) steel cylinder covered with a brass water jacket sleeve; F and G) ignition distributors; H) spark plug; h) cylinder head bolts; I) fuel distributor to the intake valve; J) cooling water inlet; K) cylinder mounting bolt; P) engine mounting flange; S and T) gears for the ignition distributors; U) crankshaft gear; V) camshaft gear.

The Aéroplane de Villotran’s failure to fly, and the fact that no other aircraft had yet flown, made the concept of an aircraft engine seem futile. However, Levavasseur and Gastambide knew the engine held great potential and turned to motorboat racing as a way for the engine to prove its worth. From 1904 through 1906, Levavasseur’s engines powered a number of motorboats that achieved various distance speed records. It was to some of these motorboats that the “Antoinette” name was first given. In some cases, V-8 engines were coupled in tandem to create a more substantial power unit. By 1908, the Antoinette company had ended its support for motorboat racing and focused on using its engines only for aviation.

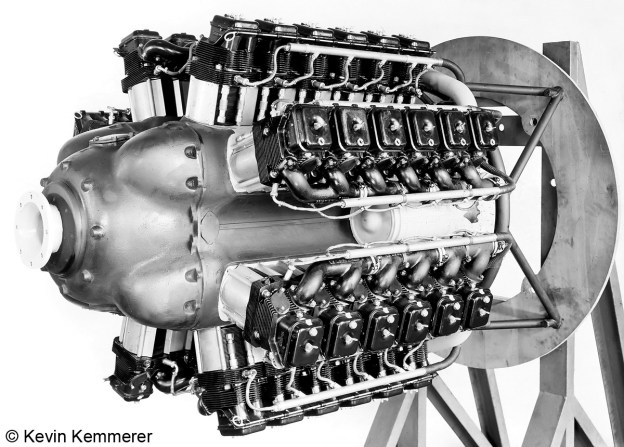

In 1904, while his engine was beginning to gain fame, Levavasseur designed other engines. Using the 80 hp (60 kW) V-8 as a foundation and maintaining the 5.12 in (130 mm) bore and stroke, Levavasseur designed V-16, V-24, and V-32 engines. Levavasseur believed that engines with many cylinders created frequent power pulses that smoothed out the engine’s operation and caused less stress on its internal components. The V-16 displaced 1,685 cu in (27.6 L) and produced 155 hp (116 kW). The V-24 displaced 2,527 cu in (41.4 L) and produced 225 hp (168 kW). The V-32 was most likely never built, but it would have displaced 3,370 cu in (55.2 L) and produced around 300 hp (224 kW).

A Bléroit IX aircraft under construction in 1908 with a 50 hp (37 kW) Antoinette V-16 installed in its frame. From left to right, the Bléroit mechanics are Louis Peyret, Louis Paragot, M. Pelletier, Alfred Bertrand, and Julien Mamet.

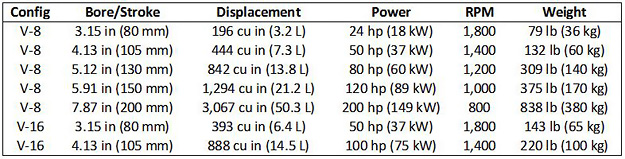

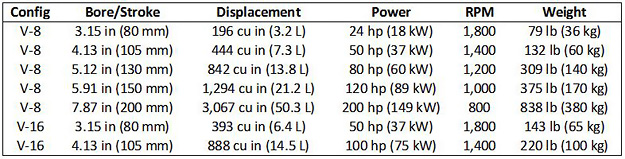

Levavasseur also varied the bore and stroke to make engines of different sizes and power. In 1905, Levavasseur built a V-8 Antoinette engine with a 3.15 in (80 mm) bore and stroke for aviation pioneers Ferdinand Ferber and Alberto Santos-Dumont. The engine displaced 196 cu in (3.2 L) and produced 24 hp (18 kW). The engine went through some refining and eventually weighed only 79 lb (36 kg). Another V-8 used a 4.13 in (105 mm) bore and stroke to displace 444 cu in (7.3 L). This engine produced 50 hp (37 kW) and weighed 176 lb (80 kg). The engine was approximately 32 in (.81 m) long, 24 in (.62 m) wide, and 22 in (.55 m) tall. A large V-8 was also built with a 7.87 in (200 mm) bore and stroke. Undoubtedly for marine use, this engine displaced 3,067 cu in (50.3 L), produced 200 hp (149 kW), and weighed 838 lb (380 kg).

In 1906, Levavasseur built a large V-24 Antoinette engine for marine use. The V-24 had a 5.91 in (150 mm) bore and stroke and displaced 3,882 cu in (63.6 L). The engine produced 360 hp (268 kW) and weighed some 1,322 lb (600 kg). Some sources say this engine was too heavy for the intended boat, which ended up sinking. The specifics of this incident have not been found.

A later model 50 hp (37 kW) Antoinette V-8 with an extended propeller shaft on display at the Muzeum Lotnictwa Polskiego in Krakow, Poland. Note the different lengths of the air intake pipes and that the water jackets are made from copper. (Alan Wilson image)

An Antoinette automobile made its debut in the 1906 Salon de l’Automobile in Paris, and some Antoinette engines were built for automotive use, these being a slightly different design and heavier than the aviation engines. Adams Manufacturing Company in London built a small number of the automotive engines under license for cars they were manufacturing.

By 1907, V-16 versions of the 3.15 in (80 mm) bore/stroke and 4.13 in (105 mm) bore/stroke engines were being built. The 3.15 in (80 mm) bore and stroke V-16 displaced 393 cu in (6.4 L), produced 50 hp (37 kW), and weighed around 143 lb (65 kg). The 4.13 in (105 mm) bore and stroke V-16 displaced 888 cu in (14.5 L), produced 100 hp (75 kW), and weighed 220 lb (100 kg). The 100 hp V-16 engine’s approximate dimensions were 55 in (1.40 m) long, 24 in (.62 m) wide, and 22 in (.55 m) tall.

The basic specifications of various Antoinette engines available circa 1907.

In addition to the V-16 engines listed above, Levavasseur offered Antoinette V-8 engines with five bore/stroke combinations. The V-8 engines had bores/strokes of 3.15, 4.13, 5.12, 5.91, or 7.87 in (80, 105, 130, 150, or 200 mm); the smallest two were mainly used for aviation.

It seems that around 1908 Levavasseur ceased experimenting with different engines and began working to refine the popular types. Levavasseur incorporated many changes to the Antoinette engines, but not all of the changes were applied at the same time. An elongated propeller shaft housing of approximately 12 in (.30 m) was cast integral with the crankcase. This feature made for a very aesthetically pleasing installation when the engine was used in an Antoinette aircraft. The battery-powered coil ignition was replaced by an accumulator and high-frequency distributor. A new one-piece, steel cylinder was used in which the cylinder head was integral with the cylinder barrel. This construction allowed for a higher compression ratio. New one-piece water jackets made of either brass or copper surrounded the new cylinders. The water jacket was unusual in that it was made by electrolytically depositing metal onto a wax mold that had been coated with graphite as a conductive material. The wax was then melted out, leaving a formed water jacket as thin as .04 in (1 mm). While this method of construction could yield perfect parts, it was expensive, and there was a high rejection rate because of irregularities in the water jacket wall.

Antoinette VII aircraft with a 100 hp (75 kW) V-16 engine displayed at the Salon de l’Aeronautique in 1909. Most sources indicate the condenser used aluminum tubes and copper side manifolds, details that this image seems to support.

By 1908, Levavasseur had perfected a zero-loss steam-cooling method for the Antoinette engines that were installed in Antoinette aircraft. The system used the same basic routing as the normal cooling system, but the water was allowed to boil in the water jackets. The steam was then collected and sent to a water separating tank. From the tank, the steam was sent though large condensers made of aluminum tubing with copper side manifolds. The condensers were positioned horizontally on each side of the aircraft. The steam condensed back to water and was routed back to the separating tank by a second pump. From the separating tank, the water was pumped back to the engine. The system condensed .26 gallons (1 L) of water per minute, and its capacity was 3.17 gallons (12 L). By reducing the amount of water needed, the steam-cooling method weighed less than conventional water-cooling.

Four Antoinette engines were displayed at the first Paris Salon de l’Aeronautique, starting in December 1908. A V-8 and V-16 were still offered with bores and strokes of 3.15 in (80 mm). However, the engines’ weights had increased to 93 lb (42 kg) for the V-8 and 165 lb (75 kg) for the V-16. The other two engines were a V-8 and V-16 with a bore of 4.33 in (110 mm) and a stroke of 4.13 in (105 mm). The V-8 engine displaced 487 cu in (8.0 L) and weighed 209 lb (95 kg). The V-16 engine displaced 974 cu in (16.0 L) and weighed 264 lb (120 kg). Some sources list the larger bore engines as producing 50 hp (37 kW) and 100 hp (75 kW) respectively. However, other sources give the outputs as 67 hp (50 kW) and 134 hp (100 kW). Note that the kW values (50 and 100) of the second figures match the hp values of the first figures. Possibly a printing error, the higher power figures have been found in fairly early publications and have been repeated a number of times over the years. The weight increases for all four engines were a result of strengthening components to increase Antoinette engine reliability.

A late model 50 hp (37 kW) Antoinette V-8 on display in the Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace. Note that this engine used brass water jackets; the piping and water manifolds were made from copper. (Aerofossile2012 image)

Alberto Santos-Dumont, Paul Cornu, Louis Blériot, Gabriel and Charles Voisin, Henri Farman, Léon Delagrange, Samuel Cody, and Hubert Latham are just some of the pioneers who used Antoinette engines to power their flying machines and themselves into the record books. Outside of the Wright brothers, almost all early aviation “firsts” were achieved in machines powered by an Antoinette engine. It was a 100 hp (75 kW) V-16-powered Antoinette aircraft that Latham flew during the aviation meet at Reims, France in August 1909 and for the Gordon Bennett Cup at Belmont Park, New York in October 1910.

With the success of the engine, Levavasseur began to focus entirely on building aircraft. From 1908 on, little engine development was undertaken to keep the Antoinette engines at the forefront of aviation. The Antoinette aircraft were built with the same spare-no-expense mentality as the engines, which resulted in them being priced far above the competition. To make matters worse, the aircraft proved to be a challenge to fly. At the same time, other engine manufactures closed the developmental gap, and the expensive Antoinette engines were no longer the coveted power plant they once were. These factors conspired to put the Antoinette company out of business in 1912.

Latham’s 100 hp (75 kW) V-16-powered Antoinette VII aircraft at Belmont Park, New York in October 1910 for the Gordon Bennett Cup. Note the length of the condenser, which extends some 13 ft (4 m) along the side of the aircraft.

While Levavasseur was most likely the first to build a V-8 engine, it is a near certainty that he was the first to create V-16 and V-24 engines. Very little information can be found regarding the V-24 marine engine. Some sources state that Levavasseur also built a V-32 intended for marine use, while other sources claim the engine did not proceed past the design phase.

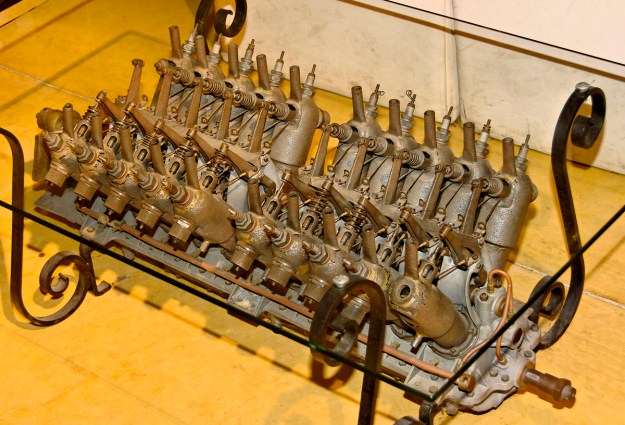

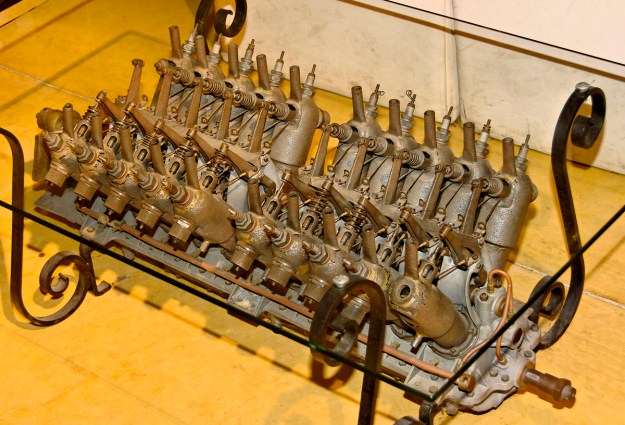

Some sources state that Levavasseur also built V-12 and V-20 engines. These engines, especially the V-20, depart from Levavasseur’s known engine layout with a V-8 at its core. While no photographs of Levavasseur’s V-12 (or V-32) engine have been found, the V-20 engine does still exist (albeit as a table). The V-20’s cylinders, valves, and valve train do not match any other engine built by Levavasseur. There was a commonality of components and configuration from Levavasseur’s earliest engine of 1903 to his last of circa 1910. The components that make up the V-20, reportedly built in 1905, are unique to that engine and are not common with any other Levavasseur engine. This component incompatibility would lead some to conclude that the V-20 engine was not built by Levavasseur.

An Antoinette VII aircraft with a 50 hp (37 kW) V-8 engine on display in the Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace. Note how well the engine fits into the aircraft and that the condensers appear to be made entirely of copper. For cooling, steam flowed from the top of the water jackets into a separation tank. The steam then flowed from the tank into the condenser, where it returned to water. The water was then pumped from the condenser into the bottom of the separation tank and back to the engine. (Pline image)

Levavasseur’s Antoinette engines were essentially the first commercially available aircraft engine and represented the pinnacle of performance in the early days of aviation. Just about every early European aviation pioneer’s first flight was powered by an Antoinette, but the engines’ reliability left much to be desired. While some changes were incorporated over the years, and their reliability did improve, the basic engine did not change much. Just before 1910, other engines (the Gnome rotary in particular) offered similar power for a similar weight but were often more reliable than the Antoinettes.

Note: Many sources give similar but completely different values for Antoinette engine dimensions, bores, strokes, and outputs. Some discrepancies can be attributed to numerous unit conversions being applied, and some of the power discrepancies can be attributed to the engines having different outputs at different rpms. Sadly, it seems that detailed specifics were not recorded in those early days of aviation; therefore, there can be no absolute certainty about the various Antoinette engine models or their histories.

The V-20 engine as displayed at Le Manoir de l’Automobile et des Vieux Métiers in Lohéac, France. Regardless of the V-20’s origins, it seems rather inglorious for such machinery to be turned into furniture. However, the engine would have probably been scrapped long ago had it not found favor as a conversation piece. Apparently, its conversion to a table consisted of nothing more than bolting on legs to preexisting mounts, something that could easily be reversed for a more befitting display. (ZANTAFIO56 image)

Sources:

– Bléroit: Herald of an Age by Brain A. Elliot (2000)

– Les moteurs et aéroplanes Antoinette by Gérard Hartmann (13 August 2007) 7.4 MB pdf in French

– The Art of Aviation by Robert W. A. Brewer (1910)

– The Passion That Left the Ground by Stephen H. King (2007)

– Vingt Cinq Ans d’Aéronautique française: 1907-1932 Tome 1 (1934)

– “The First Paris Aeronautical Salon: Engines for Aeroplanes” Flight (16 January 1909)

– “How Levavasseur Built his Light Motor” by Ferdinand Ferber The Automobile (28 March 1907)

– “Historie du moteur Antoinette” by Ferdinand Ferber l’Aérophile (15 February 1908)

– “Moteur à huit cylindres” French patent 339,068 by Léon Levavasseur (applied 28 August 1903)

– “Carbureter” US patent 878,297 by Léon Levavasseur (applied 16 may 1907)

– “Umsteuerungsvorrichtung für Mehrzylinder-Explosionskraftmaschinen” Austrian patent 25,610 by Léon Levavasseur (applied 14 September 1904)

– Airplane Engine Encyclopedia by Glenn Angle (1921)

– http://www.theaerodrome.com/forum/showthread.php?t=57838