By William Pearce

An airboat is a vessel that has a shallow draft and utilizes the thrust generated by an aircraft propeller to drive over ice, grass, or water. The airboat concept started as a way to test propellers but evolved into a nearly indispensable form of transportation though swampy areas. In Italy in the 1930s, the concept of an airboat was taken a bit further.

The Isotta Fraschini Asso 200-powered SIAI hydroplane that Franco Mazzotti and Guido Cattaneo drove to victory in the 1930 and 1931 Raid Pavia-Venezia.

First run in 1929, the Raid Pavia-Venezia was an inshore powerboat race of around 269 miles (433 km) held in June. The course distance varied slightly by year. Starting on the Ticino River in Pavia, Italy, the race transitioned to the River Po and then through canals, finally ending in Venice. Fuel stops were incorporated along the route. Various parts of the course had many turns, hidden sandbars, and tight passageways. The Raid Pavia-Venezia was the creation of Vincenzo Balsamo, an engineer, sailor, and head of the Gruppo Motonautico della Lega Navale di Milano (Powerboat Section of the Navy League of Milan), the group that organized the race. The 1929 race was completed in 11:26:23 at an average of 22.164 mph (35.670 km/h).

Attilio Biseo and Gino Bertoli won the 1932 Raid Pavia-Venezia in this SIAI idroscivolante powered by a FIAT A50 engine. (image via Three Point Hydroplanes)

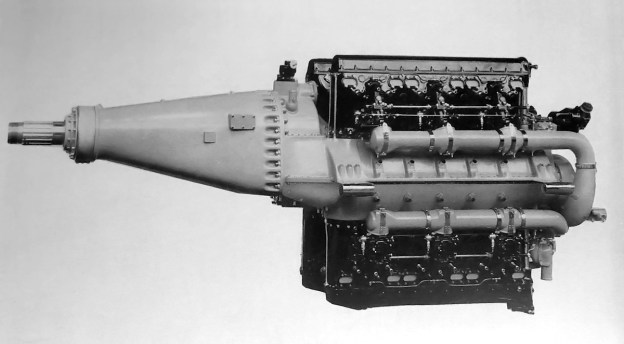

The 1930 race marked the start of combining powerful Italian aircraft engines with shallow-hulled hydroplanes to create the idroscivolante (airboat). Idroscivolanti (airboats) would not only increase straight line speeds, they would also allow the boats to travel over shallow sandbars without worry. Only one idroscivolante was entered in the 1930 race. It used an Isotta Fraschini (IF) Asso 200 engine that turned a four-blade, wooden propeller. The Asso 200 was a 200 hp (149 kW), water-cooled, inline-six engine. It was mounted in a pusher configuration to the rear of a shallow-hulled boat built by SIAI (Società Idrovolanti Alta Italia or Northern Italy Seaplane Company, also known as Savoia-Marchetti). Driven by Count Franco Mazzotti with co-driver Guido Cattaneo, the SIAI/IF idroscivolante won the race with a time of 8:10:35, averaging 31.462 mph (50.633 km/h). The second place finisher was nearly an hour behind the idroscivolante.

The Celli hydroplane powered by an SPA 6A engine in a pusher configuration. Aldo Salom and Dino Celli campaigned this boat in 1933 and 1934. (image via Three Point Hydroplanes)

Mazzotti and Cattaneo won the 1931 race again in the SIAI/IF idroscivolante with a time of 6:52:54 and averaging 38.309 mph (61.653 km/h). However, they had competition in the form of driver Count Theo Rossi and co-driver Alfredo Stracconi in a Passarin idroscivolante powered by a FIAT (Fabbrica Italiana Automobili Torino or Italian Automobile Factory Turin) A50 engine. The A50 was an air-cooled, seven-cylinder, radial engine that produced 105 hp (78 kW). Rossi and Stracconi finished the race in second place at 33.648 mph (54.151 km/h).

Rossi and Stracconi were back in their Passarin/FIAT in 1932, but they were unable to complete the race. The only other idroscivolante was a SIAI powered by a FIAT and driven by Attilio Biseo and Gino Bertoli. The FIAT A50 radial engine was mounted in a tractor configuration on struts in the middle of the boat. Biseo and Bertoli won the 1932 race in 5:27:26 at a 47.138 mph (75.862 km/h) average speed. Biseo and Bertoli finished the Raid Pavia-Venezia 2:30:01 before the first conventional powerboat.

Theo Rossi and Guido Cattaneo paired up to compete in the Raid Pavia-Veneziain in this SIAI idroscivolante powered by an IF Asso 200 engine. This photo was most likely taken in 1934. (image via Three Point Hydroplanes)

For 1933, Theo Rossi and Guido Cattaneo joined forces in the SIAI/IF. The SIAI/FIAT idroscivolante was entered by driver Marcello Visconti di Modrone and co-driver Franco Mazzotti, but it did not finish the race. Rossi and Cattaneo took the win with a time of 6:37:14, averaging 40.639 mph (65.402 km/h) over the whole course. The pair averaged 56.511 mph (90.946 km/h) over the 37 miles (60 km) between Piacenza and Cremona.

In 1934, two of the three idroscivolanti entered in the race failed to finish. One of the non-finishers was a new, small SIAI hydroplane raced by Rossi and Cattaneo. It was powered by a 200 hp (149 kW) IF Asso 200 inline-six engine in a tractor configuration and housed in a streamlined cowling; the engine and propeller were probably from the previous SIAI/IF boat. The other idroscivolante that did not finish was a Celli hydroplane powered by a SPA (Società Ligure Piemontese Automobili or Ligure Piemontese Automobile Company) 6A engine and raced by Aldo Salom and Dino Celli. Their 205 hp (153 kW) inline-six engine was mounted at the rear of the boat in a pusher configuration and turned a four-blade, wooden propeller. The race was won by driver Attilio Biseo with co-driver Renato Donati in a SIAI hydroplane powered by a Farina T.58 135 hp (101 kW), air-cooled, five-cylinder, radial engine. The engine turned a two-blade propeller and was mounted in a tractor position at the middle of the boat. Their time was 5:44:08 with an average of 47.188 mph (75.942 km/h).

Attilio Biseo and Renato Donati competing in the 1934 race, which they won. Their SIAI idroscivolante was powered by a Farina T.58 engine. (image via Three Point Hydroplanes)

Four idroscivolanti competed in the 1935 Raid Pavia-Venezia. Driver Renato Donati and co-driver Federico Borromeo finished in sixth place overall. Their sleek, two-hulled, catamaran idroscivolante was designed by the Laboratorio Sperimentale Regia Aeronautica (Royal Italian Air Force Experimental Laboratory) but was most likely built by SIAI. It was powered by an air-cooled, seven-cylinder, 200 hp (149 kW) Alfa Romeo Lynx radial engine based on the Armstrong Siddeley Lynx and produced under license. The engine turned a three-blade, metal propeller and was mounted in a tractor configuration in the middle of the idroscivolante. In fourth place overall were Aldo Salom and Dino Celli in the Celli/SPA. In second place were driver Goffredo Gorini and co-driver Francesco Bertoli in the sister ship of Donati and Borromeo. However, their idroscivolante did not have a deck connecting the two hulls. Gorini and Bertoli finished the race in 5:12:30 and averaged 51.652 mph (83.126 km/h). The winners of the 1935 race were Rossi and Cattaneo in the SIAI/IF. Their boat had been modified with larger fuel tanks that bulged out above the two-hulls. Rossi and Cattaneo completed the race in 5:01:50 at 53.483 mph (86.073 km/h). They averaged 69.326 mph (111.570 km/h) over the 37 miles (60 km) from Piacenza to Cremona.

Renato Donati and Federico Borromeo in the Laboratorio Sperimentale Regia Aeronautica powered by an Alfa Romeo Lynx in 1935. Note the deck connecting the hulls. The idroscivolante sits in Venice’s Grand Canal with the Santa Maria della Salute in the background. (image via Three Point Hydroplanes)

Theo Rossi and Guido Cattaneo took another win in their SIAI/IF for 1936. Their time was 4:45:02 at an average speed of 56.576 mph (91.051 km/h), and they finished over three hours before the first conventional powerboat. Second place was won by Vito Mussolini and Carlo Maurizio Ruspoli in the SIAI/Farina. Vito Mussolini was Benito Mussolini’s nephew, and Carlo Maurizio Ruspoli was a Prince of Poggio Suasa. The third and last idroscivolante entered in the 1936 race was the Laboratorio Sperimentale Regia Aeronautica/Alfa Romeo of Goffredo Gorini and Renato Donati. While they did not finish the race, they did average 74.191 mph (119.400 km/h) over the 43 miles (69 km) between Pavia and Piacenz.

A race was also run on the Danube River between Vienna and Budapest in 1936. Which idroscivolanti participated and the results of the race have not been found. It can be assumed that the SIAI/IF idroscivolante raced by Rossi and Cattaneo did participate in this race, as it had “Vienna-Budapest” painted on its hull during the Pavia-Venezia race. At around 177 miles (285 km), the Vienna-Budapest race was about two-thirds the distance of the Raid Pavia-Venezia.

The other Laboratorio Sperimentale Regia Aeronautica/Alfa Romeo driven by Goffredo Gorini and Francesco Bertoli in the 1935 Raid Pavia-Venezia. (image via Three Point Hydroplanes)

In 1937, driver Goffredo Gorini and co-driver Renato Donati won the race. Their idroscivolante was referred to as an SIAI, replacing Laboratorio Sperimentale Regia Aeronautica. The boat was still powered by an Alfa Romeo Lynx, but the engine struts and supports had been redesigned. In addition, a wide cord, two-blade, metal propeller was used. Gorini and Donati’s winning time was 4:47:32 with an average speed of 56.143 mph (90.354 km/h). In the sister ship, Prospero Freri and Salvatore Flamini took second place just 10 minutes behind the leader, with an average speed of 54.175 mph (87.186 km/h). Their idroscivolante was referred to as a CNA (Compagnia Nazionale Aeronautica or National Aeronautical Company), replacing Laboratorio Sperimentale Regia Aeronautica. The catamaran had new engine struts that now supported a nine-cylinder, 240 hp (179 kW) Alfa Romeo D.2 engine turning a three-blade, metal propeller. A Townend ring intended to reduce drag and improve engine cooling encircled the D.2’s cylinders. Theo Rossi and Guido Cattaneo, the previous year’s winners, placed third in their SIAI/IF.

Theo Rossi and Guido Cattaneo won the 1936 race in the SIAI/IF idroscivolante. Note the increased capacity fuel tanks that bulged above the deck and that “Budapest” is written on the hull. (image via Three Point Hydroplanes)

1938 saw five idroscivolanti entered in the Raid Pavia-Venezia race. Goffredo Gorini and Marco Ponzalino won the race in a SIAI/Alfa Romeo at a very fast time of 4:11:28, averaging 64.193 mph (103.308 km/h). Prospero Freri and Salvatore Flamini in the CNA/Alfa Romeo finished in second place. Vito Mussolini and Luciano Agosti took third place in the SIAI/Farina. Marco Celli and Aldo Tassinari finished in eighth place overall in a Celli catamaran powered by a 115 hp (86 kW) Walter Venus engine. On this boat, the seven-cylinder radial engine turned a three-blade propeller and was strut-mounted in a tractor configuration on the rear half of the catamaran. The last idroscivolante finished in ninth place overall; it was Aldo Salom and Bruno Rocca in a Celli hydroplane powered by an IF Asso 200 inline-six engine. The engine turned a four-blade, wooden propeller and was rear-mounted in a pusher configuration. Theo Rossi and Guido Cattaneo did not finish in their SIAI/IF.

Vito Mussolini and Carlo Maurizio Ruspoli competing in the 1936 Raid Pavia-Venezia in the SIAI/Farina idroscivolante. (image via Three Point Hydroplanes)

In 1939, Goffredo Gorini and Marco Ponzalino won the Raid Pavia-Venezia again at a slightly slower pace than the previous year. They finished in 4:19:16 at an average speed of 62.264 mph (100.205 km/h). The pair averaged 79.477 mph (127.80 km/h) over the 43 miles (69 km) from Pavia to Piacenz and finished the race 3:32:44 before the first conventional powerboat. Sources list their idroscivolante as a Gorini powered by an Alfa Romeo engine. However, film taken during a speed run in August shows a catamaran very similar to the one used the previous year but powered by a Wright R-975 Whirlwind 330 hp (246 kW), nine-cylinder, radial engine that turned a two-blade, metal propeller. Finishing twenty-three minutes behind them was their sister ship, listed as a Gorini/Freri/Alfa Romeo. Driver Prospero Freri and co-driver Salvatore Flamini averaged 57.148 mph (91.970 km/h). Freri and Flamini’s idroscivolante no longer had a Townend ring around the engine; the Alfa Romeo D.2’s cylinders were exposed to the air. In addition, a two-blade, metal propeller was installed. Fernando Venturi and Paolo Mora finished third in a Saliman (some sources say Saimon) catamaran powered by a FIAT A50 engine. The engine of this two-hulled idroscivolante was mounted in a tractor configuration at the center of the boat and turned a two-blade, wooden propeller. The SIAI/Farina idroscivolante of Vito Mussolini and Luciano Agosti finished in fourth place.

Goffredo Gorini and Renato Donati won the 1937 race in the SIAI/Alfa Romeo idroscivolante. Note the wide cord, two-blade propeller on the Lynx engine.

In July 1939, Fernando Venturi in the Saliman/FIAT idroscivolante set an 800 kg (1,764 lb) class speed record of 49.692 mph (79.971 km/h) on Lake Bracciano. The record was broken in August when Goffredo Gorini achieved 91 mph (147 km/h) in the Wright Whirlwind-powered Gorini idroscivolante mentioned earlier. This appears to be a new idroscivolante, as the Alfa Romeo Lynx-powered machine was also present for the speed runs. Gorini had reached 96 mph (155 km/h), but technical difficulties prevented him from maintaining that speed. Gorini’s Wright-powered idroscivolante still had “Raid-Pavia-Venezia” painted on the hull from the race two months earlier.

For the 1937 Raid Pavia-Venezia, Prospero Freri and Salvatore Flamini installed a nine-cylinder Alfa Romeo D.2 engine with a three-blade propeller and a Townend ring. The pair took second place in 1937, 1938, and 1939. This photo is from the 1938 race.

The Raid Pavia-Venezia was suspended in 1940 due to World War II. The race was held again in 1952, but the idroscivolanti were no longer allowed to compete. The 1952 and 1953 winners were slower than the idroscivolanti of the 1930s, but technology progressed quickly, and conventional powerboats soon outpaced the idroscivolanti. The large, powerful aircraft engines allowed the idroscivolanti to reach high speeds, but with limited fuel on board the sleek machines, more frequent fuel stops were required. Only around 12 idroscivolanti were built, but their type won all ten of the Raid Pavia-Venezia in which they participated, outpacing conventional powerboats by more than three hours over the 269 mile (433 km) course.

Fernando Venturi and Paolo Mora’s FIAT-powerd Saliman in 1939. The idroscivolante finished the race in third place and went on to set a short-lived speed record of 49.692 mph (79.971 km/h) in July 1939. Santa Maria della Presentazione (Le Zitelle) is in the background. (image via Three Point Hydroplanes)

In August 1951, Franco Venturi, Fernando’s son, set an 800 kg (1,764 lb) class speed record of 97 mph (156 km/h) on Lake Sabaudia. The idroscivolante used for this record run was the same two-hulled catamaran used by Goffredo Gorini in 1939 to win the Raid Pavia-Venezia and establish an 800 kg speed record. However, the idroscivolante was modified with a three-blade, metal propeller attached to the Wright R-975 Whirlwind engine. With idroscivolanti banned from the Raid Pavia-Venezia, Franco Venturi eventually donated the machine to the Museo della Scienza e della Tecnologia “Leonardo da Vinci” (Museum of Science and Technology “Leonardo da Vinci”) in Milan, Italy, where it is currently preserved.

The Gorini/Wright idroscivolante used to set a speed record in 1939 by Goffredo Gorini at 91 mph (147 km/h) and in 1951 by Franco Venturi at 97 mph (156 km/h). (image via Museo della Scienza e della Tecnologia)

Prospero Freri managed to save the idroscivolante that he drove to second place finishes in 1937, 1938, and 1939. Numbered 108 and later T-108, the racer had deteriorated over the years. After Freri passed away in 1965, his heirs donated T-108 to the Civico Museo Navale Didattico di Milano (Civic Museum of Naval Education of Milan) in 1967. In 2006, T-108 underwent a seven month restoration by the Dalla Pietà boatyard in Malcontenta. At the beginning of the restoration, T-108 had “XII Raid Pavia-Venezia” painted on the hull, indicating Freri had prepared the idroscivolante for the 1940 race (the 12th Raid Pavia-Venezia). After the restoration, the hull was painted “XI Raid Pavia-Venezia” (indicating the 1939 race) to eliminate any confusion. T-108 is currently on display in the Museo della Scienza e della Tecnologia “Leonardo da Vinci”.

Sadly, there is very little information on the idroscivolanti, and what information can be found is occasionally contradictory. The timeline in this article was developed by cross referencing existing information with contemporary photos and videos. While every effort was made to maintain accuracy, there is no guarantee the article is entirely correct. Most of material for this article came from Three Point Hydroplanes, a historical archive of Italian hydroplanes.

The Alfa Romeo D.2-powered idroscivolante driven by Prospero Freri and Salvatore Flamini to second place in the 1937, 1938, and 1939 races. It was restored to its 1939 Raid Pavia-Venezia configuration in 2007. (image via Dalla Pietà Yatch)

Idroscivolanti results in the Raid Pavia-Venezia

1930

1) Franco Mazzotti and Guido Cattaneo in the SIAI/Isotta Fraschini

8:10:35 averaging 31.462 mph (50.633 km/h)

1931

1) Franco Mazzotti and Guido Cattaneo in the SIAI/Isotta Fraschini

6:52:54 averaging 38.309 mph (61.653 km/h)

2) Theo Rossi and Alfredo Stracconi in the Passarin/FIAT

7:38:43 averaging 33.648 mph (54.151 km/h)

1932

1) Attilio Biseo and Gino Bertoli in the SIAI/FIAT

5:27:26 at 47.138 mph (75.862 km/h)

DNF) Theo Rossi and Alfredo Stracconi in the Passarin/FIAT

1933

1) Theo Rossi and Guido Cattaneo in the SIAI/Isotta Fraschini

6:37:14 averaging 40.639 mph (65.402 km/h)

DNF) Marcello Visconti di Modrone and Franco Mazzotti in the SIAI/FIAT

1934

1) Attilio Biseo and Renato Donati in the SIAI/Farina

5:44:08 averaging 47.188 mph (75.942 km/h)

DNF) Theo Rossi and Guido Cattaneo in the SIAI/Isotta Fraschini

DNF) Aldo Salom and Dino Celli in the Celli/SPA

1935

1) Theo Rossi and Guido Cattaneo in the SIAI/Isotta Fraschini

5:01:50 averaging 53.483 mph (86.073 km/h)

2) Goffredo Gorini and Francesco Bertoli in the Laboratorio Sperimentale Regia Aeronautica/Alfa Romeo

5:12:30 averaging 51.652 mph (83.126 km/h)

4) Aldo Salom and Dino Celli in the Celli/SPA

6:26:18 averaging 41.789 mph (67.253 km/h)

6) Renato Donati and Federico Borromeo in the Laboratorio Sperimentale Regia Aeronautica/Alfa Romeo

7:20:28 averaging 36.650 mph (58.982 km/h)

1936

1) Theo Rossi and Guido Cattaneo in the SIAI/Isotta Fraschini

4:45:02 averaging 56.576 mph (91.051 km/h)

2) Vito Mussolini and Carlo Maurizio Ruspoli in the SIAI/Farina

5:29:02 averaging 44.967 mph (72.367 km/h)

DNF) Goffredo Gorini and Renato Donati in the Laboratorio Sperimentale Regia Aeronautica/Alfa Romeo

1937

1) Goffredo Gorini and Renato Donati in the SIAI/Alfa Romeo

4:47:32 averaging 56.143 mph (90.354 km/h)

2) Prospero Freri and Salvatore Flamini in the CNA/Alfa Romeo

4:57:59 averaging 54.175 mph (87.186 km/h)

3) Theo Rossi and Guido Cattaneo in the SIAI/Isotta Fraschini

5:29:22 averaging 49.013 mph (78.878 km/h)

1938

1) Goffredo Gorini and Marco Ponzalino in the SIAI/Alfa Romeo

4:11:28 averaging 64.193 mph (103.308 km/h)

2) Prospero Freri and Salvatore Flamini in the CNA/Alfa Romeo

5:34:40 averaging 48.236 mph (77.629 km/h)

3) Vito Mussolini and Luciano Agosti in the SIAI/Farina

6:37:32 at 40.614 mph (65.352 km/h)

8) Marco Celli and Aldo Tassinari in the Celli/Walter

8:13:11 averaging 32.733 mph (52.678 km/h)

9) Aldo Salom and Bruno Rocca in the Celli/Isotta Fraschini

9:25:44 averaging 28.535 mph (45.922 km/h)

DNF) Theo Rossi and Guido Cattaneo in the SIAI/Isotta Fraschini

1939

1) Goffredo Gorini and Marco Ponzalino in the Gorini/Wright

4:19:16 averaging 62.264 mph (100.205 km/h)

2) Prospero Freri and Salvatore Flamini in the Gorini/Freri/Alfa Romeo

4:42.29 averaging 57.148 mph (91.970 km/h)

3) Fernando Venturi and Paolo Mora in the Saliman/FIAT

6:10:54 averaging 43.524 mph (70.045 km/h)

4) Vito Mussolini and Luciano Agosti in the SIAI/Farina

6:16:13 averaging 42.915 mph (69.065 km/h)

Sources:

– http://www.threepointhydroplanes.it/raid-pavia-venezia_r1_en.htm (and numerous pages, images, and videos therein)

– http://www.museoscienza.org/museo/patrimonio/idroscivolanteT108.asp

– http://www.museoscienza.org/dipartimenti/catalogo_collezioni/scheda_oggetto.asp?idk_in=ST120-00498

– http://www.pionieredellanautica.it/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=47&Itemid=55

– Fernando Venturi 1939 Record Run (YouTube)

– Geoffredo Gorini 1939 Record Run (YouTube)

– Franco Venturi 1951 Record Run (YouTube)

– Aerosphere 1939 by Glenn D. Angle (1940)

– Aeronuatica Militare Museo Storico Catalogo Motori by Oscar Marchi (1980)