By William Pearce

When the United States entered World War I, the Allison Experimental Company (Allison), founded by James Allison, set out to construct equipment for the war effort. Previously, the company was known as the Allison Speedway Team Company, because James Allison was a co-founder of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and was focused on automobile development. During the war, the Allison Experimental Company supplied some of the tooling for production of Liberty V-12 engines. Throughout and after the war, Allison was involved in designing and building various Liberty parts, including the epicyclic (planetary) gear reduction for the Liberty 12B (200 of which they constructed) and various other gear reduction units, gearboxes, and superchargers. Allison also developed and produced an inverted Liberty engine and air cooled cylinders for the Liberty. The Liberty was Allison’s first foray into aircraft propulsion; its next was the X-4520.

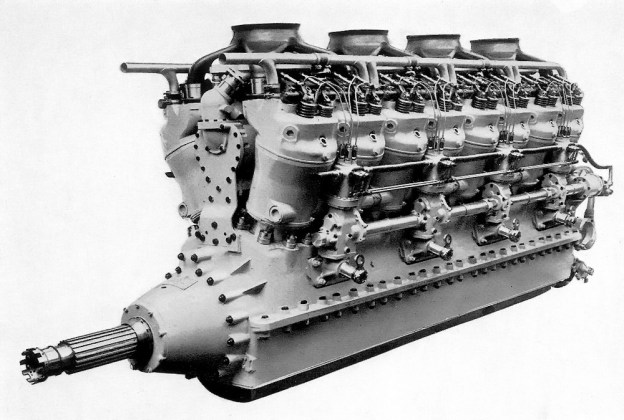

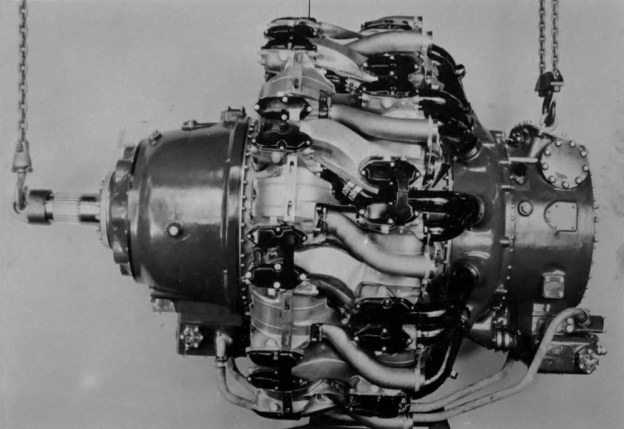

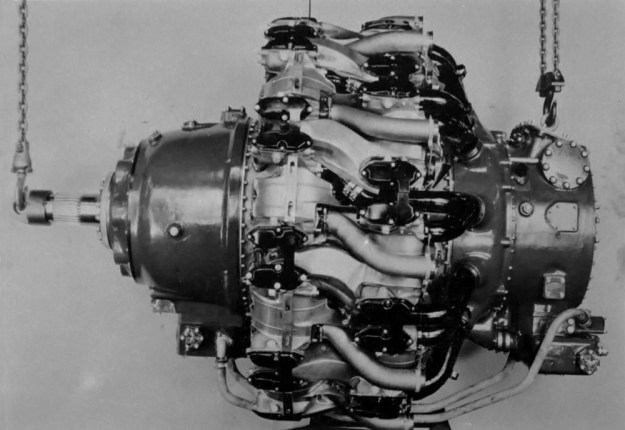

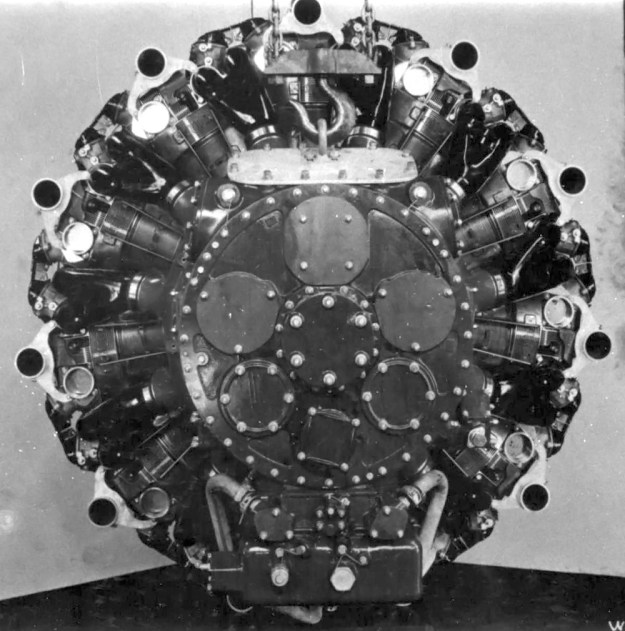

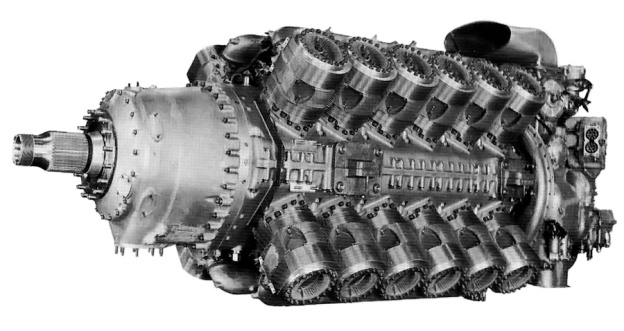

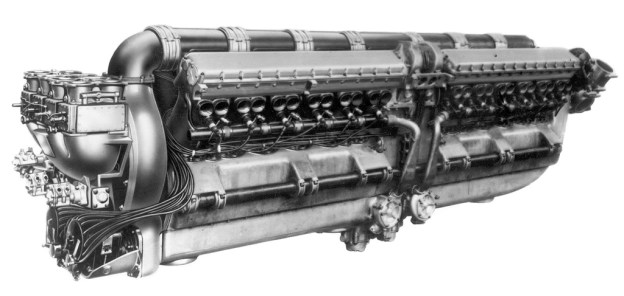

The restored Allison X-4520 24-cylinder, air-cooled engine carrying Allison serial number 1. Note the distributors on the front of each overhead camshaft. (Paul Jablonski image via the Aircraft Engine Historical Society)

On 4 January 1921, the Allison Experimental Company changed its name to the Allison Engineering Company. By 1924, the Army Air Service (AAS) Power Plant Section at McCook Field, Ohio had designed a large 24-cylinder engine in an “X” layout. They asked Allison to refine their design and construct a prototype. The engine was given the AAS serial number 25-521 and also carried the Allison serial number 1.

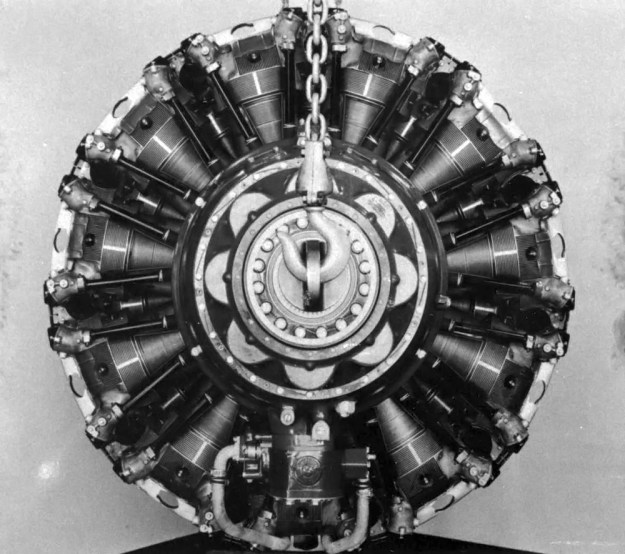

The X-4520 had four banks of six air-cooled cylinders. The banks were arranged at 90 degree intervals around a common crankshaft housed in an aluminum, barrel-type crankcase. The cylinders had a 5.75 in (146 mm) bore, 7.25 in stroke (184 mm), and 4.9 to 1 compression ratio. Total displacement was 4,518 cu in (74 L). Each cylinder had two valves, and the exhaust valve was sodium cooled. The valves for each cylinder bank were actuated by a single overhead camshaft. At the front of each camshaft was a distributor that fired the two spark plugs per each cylinder for that bank. Each camshaft was driven by the crankshaft via a vertical shaft at the front of the engine.

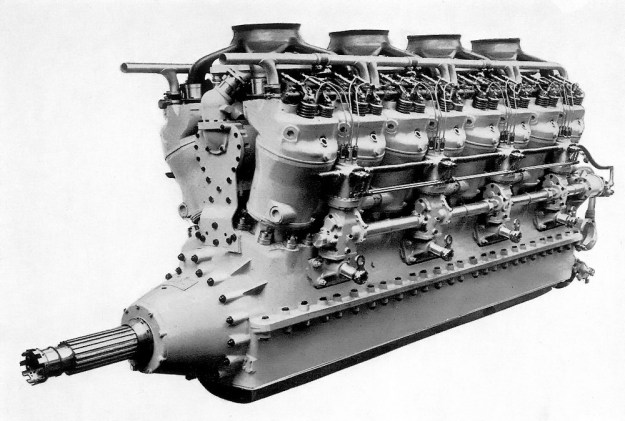

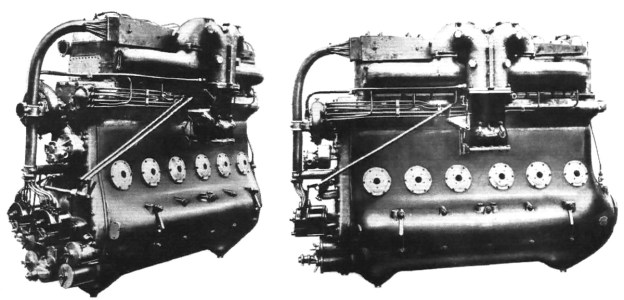

An early 1925 AAS drawing of the X-4520. The most notable differences between the drawing and the actual engine are that the drawing has the lower banks of cylinder staggered forward of the upper cylinders, and the intake manifolds exit the top and bottom of the rotary induction.

The flat top aluminum pistons had three rings above the piston pin and one ring below. Each of the six 3.5 in (89 mm) diameter crankpins was 4.3125 in (110 mm) long and accommodated two fork-and-blade connecting rods side-by-side. The top cylinder’s pistons were connected to the front fork-and-blade connecting rod. The bottom cylinders were staggered slightly to the rear, and their pistons were connected to the rear fork-and-blade connecting rod. The seven crankshaft main bearings were of the (Hoffman) roller type. Roller bearings were selected by the Power Plant Section because their reduced length allowed for a shorter, and therefore lighter, engine.

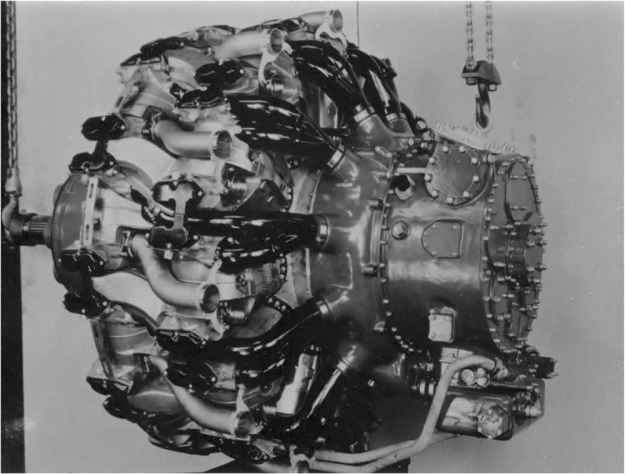

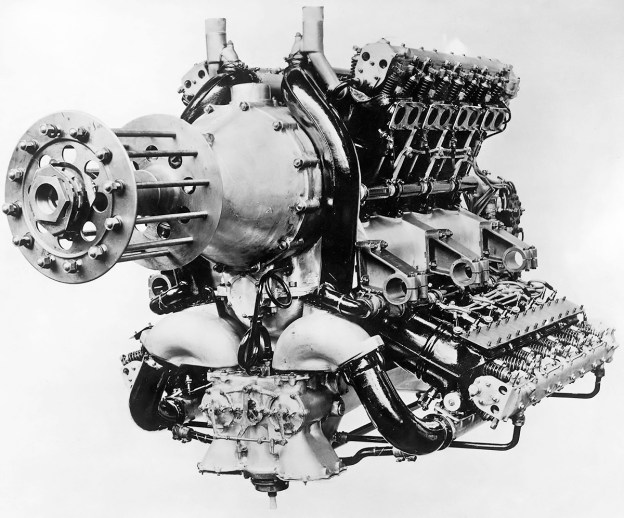

The engine had a 2 to 1 spur reduction gear and a rotary induction (fuel/air mixer or moderate supercharger) geared with a step-up ratio of 5 to 1. At 1,800 rpm engine speed, the propeller would turn 900 rpm and the supercharger 9,000 rpm. Two updraft carburetors fed the rotary induction at the rear of the engine. The air/fuel mixture was then distributed to each cylinder via manifolds that ran in the upper and lower Vees of the engine. The X-4520 was 108 in (2.74 m) long, 60 in (1.52 m) wide, 53 in (1.35 m) tall, and weighed around 2,800 lb (1,270 kg).

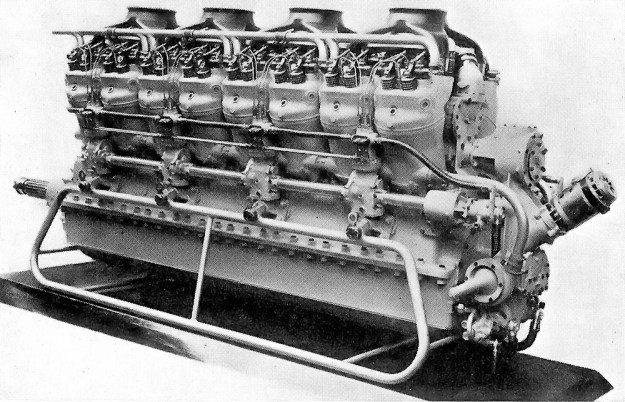

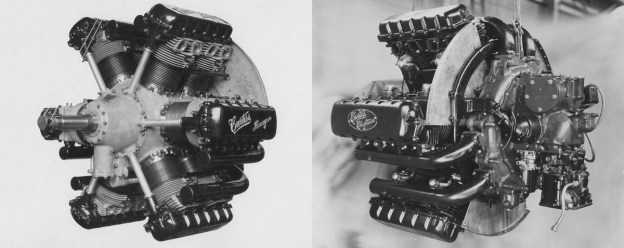

The Allison X-4520 with baffles surrounding sides of the engine to direct cooling air through the cylinder’s fins.

Allison completed the sole X-4520 engine in 1927, but no facilities existed that could handle the rated output of 1,200 hp (895 kW) at 1,800 rpm. At the time, it was one of the largest and most powerful aircraft engines ever built. It was not until 1931 that the engine was finally run by the Army Air Corps (AAC). While the engine produced 1,323 hp (987 kW) at 1,900 rpm, it also experienced cooling-issues, and a piston stuck in a cylinder during testing. By this time, the AAC had little interest in the engine, and the cause of the issues were never investigated.

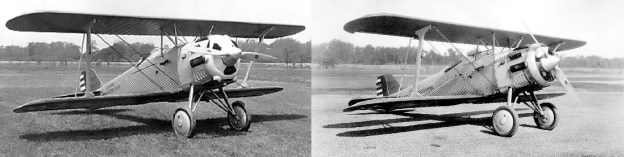

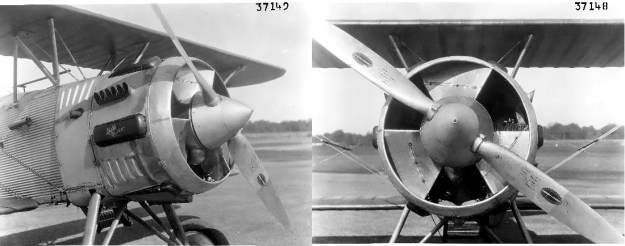

The X-4520 was intended for a very large single-engine biplane bomber, most likely the Huff-Daland XHB-1. This aircraft had an 84 ft 7 in (25.8 m) span, was 59 ft 7 in (18.2 m) long, and was fitted with a 780 hp (582 kW) Packard 2A-2540 V-12 engine. By the time the X-4520 was tested, a design shift had occurred from the use of large single-engine aircraft to multi-engine aircraft. This left the X-4520 without an application, in addition to the technical issues experienced during testing.

The huge Huff-Daland XHB-1 was originally to be powered by the X-4520. As events unfolded, the aircraft was powered by a Packard engine. The man standing under the nose of the aircraft gives a good indication of its immense size.

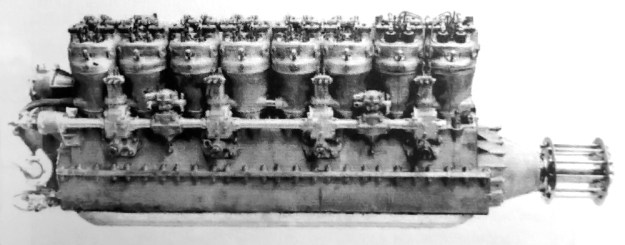

Even with the AAC’s lack of interest and the engine’s technical issues, the X-4520 was displayed at the Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago, Illinois in 1934. The engine was retained by the AAC and placed in storage at what would become Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. The X-4520 was disposed of as scrap around 1970 (apparently aviation history enthusiast Walter Spolata saved the engine). The X-4520 eventually found its way to the New England Air Museum in Windsor Locks, Connecticut, looking in rough shape after being in outside storage for a number of years. The engine was then acquired by the Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust Allison Branch in Indianapolis, Indiana; the trust restored the X-4520 and put it on display in 2010.

The Allison X-4520 on display at the Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust Allison Branch in Indianapolis, Indiana. Note the induction and how it differs from the 1925 drawing. (Paul Jablonski image via the Aircraft Engine Historical Society)

Sources:

– Vee’s for Victory! The Story of the Allison V-1710 Aircraft Engine 1929-1948 by Daniel D. Whitney (1998)

– Bearing Loads and Stress Analysis of the Model X-4520 Engine Rated 1200 B.H.P. at 1800 R.P.M. by Norman Tilley (1925)

– The Allison Engine Catalog 1915-2007 by John M. Leonard (2008)

– A Technical & Operational History of the Liberty Engine by Robert J. Neal (2009)

– http://www.enginehistory.org/allison.shtml

– http://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/factsheets/factsheet.asp?id=2422