By William Pearce

In 1934, James Martin and Captain Valentine Baker formed the Martin-Baker Aircraft Company in Denham, United Kingdom. Designed by Martin, their first aircraft was the MB1—a low-wing touring aircraft with a two-place enclosed cockpit. First flown by Capt. Baker in April 1935, the MB1’s airframe was comprised of a steel tube structure, and the wings could be folded back for transport or storage. However, with the political situation in Europe deteriorating, and with Britain in search of new fighter aircraft, Martin-Baker turned its attention to designing a new fighter: the MB2.

The MB2 started as a private venture around 1935 and closely followed Air Ministry Specification F.5/34 issued in 1934 for an eight-gun, 275 mph fighter aircraft. The MB2 was to be an easily produced and low cost fighter. Construction on the MB2 began in March 1936 and utilized the same steel tube construction techniques employed on the MB1. The wings and forward fuselage were covered by duralumin, and the rear fuselage and control surfaces were fabric covered. For simplicity and lightness, the MB2 had fixed undercarriage housed in streamlined fairings; the left fairing also incorporated an engine oil cooler. A pneumatic crash pylon would extend above the canopy to protect the pilot in the event of a nose-over during takeoff or landing.

The MB2 with the crash pylon extended above the cockpit canopy. Note that the canopy provided a 360 degree view.

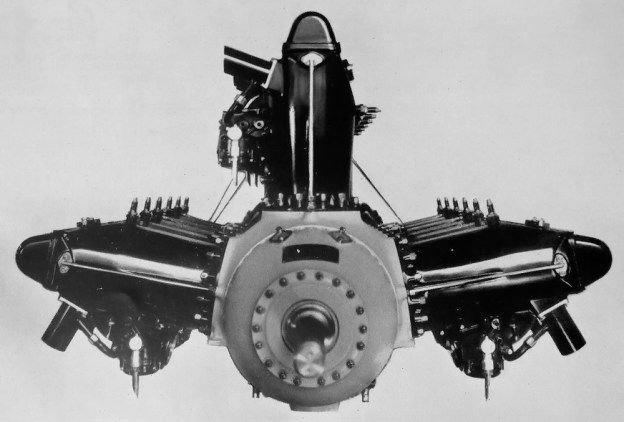

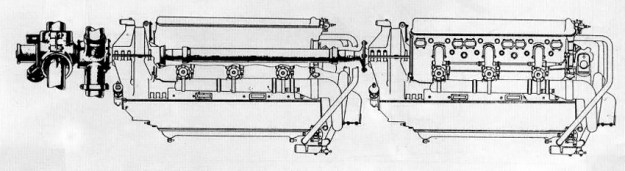

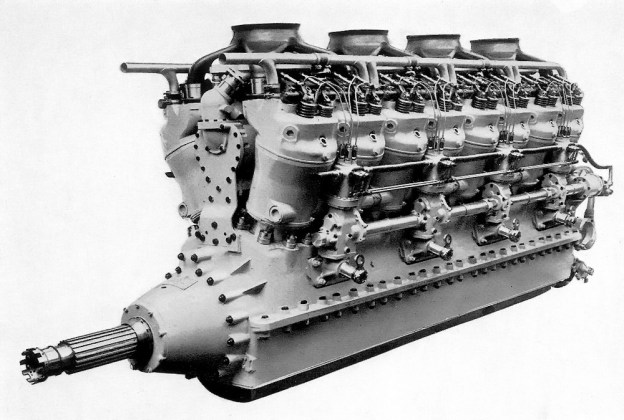

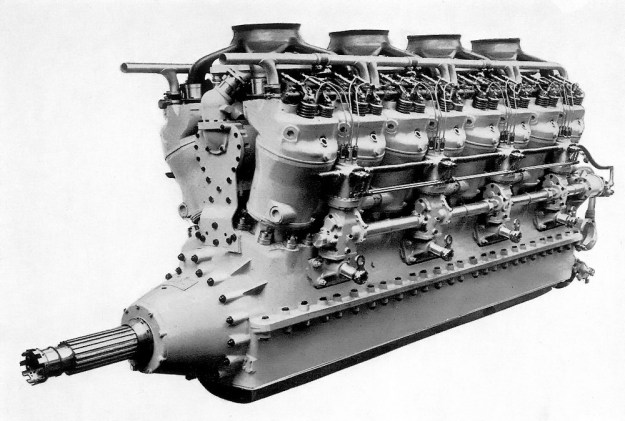

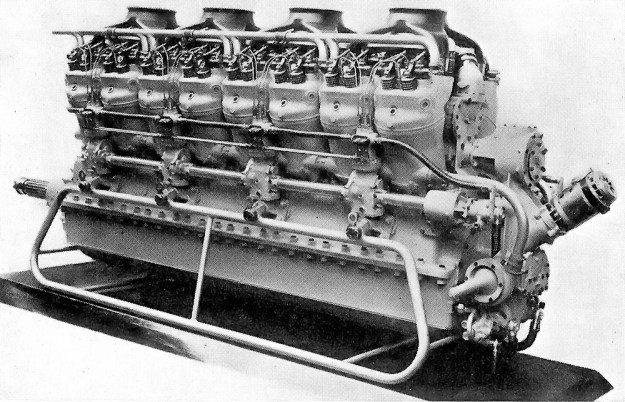

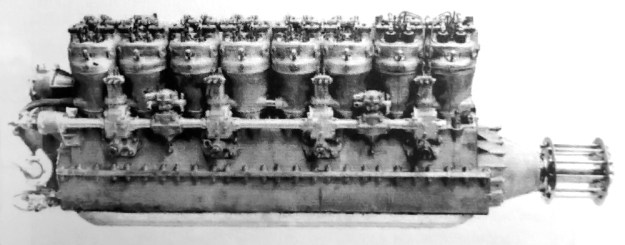

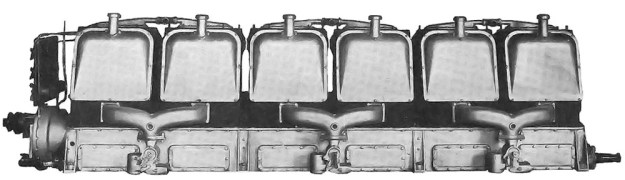

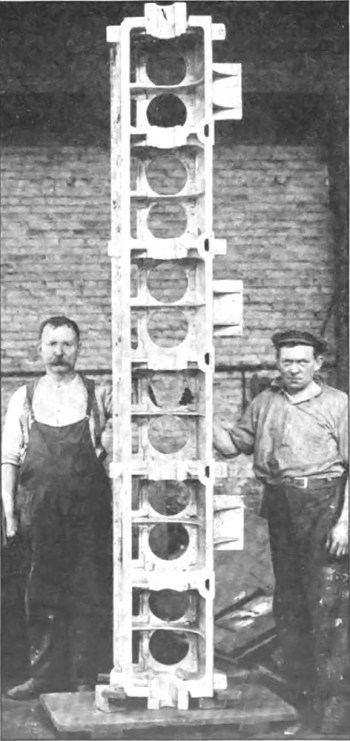

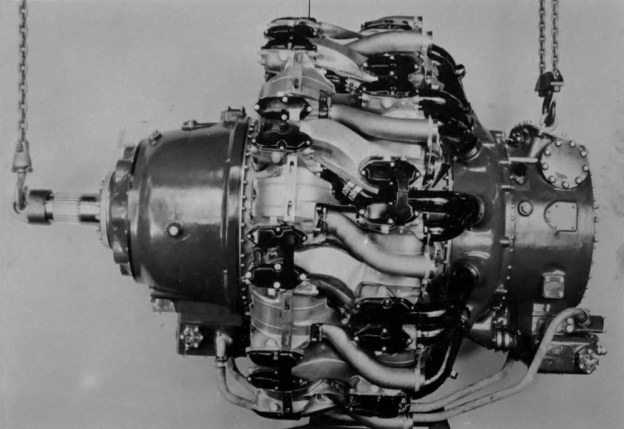

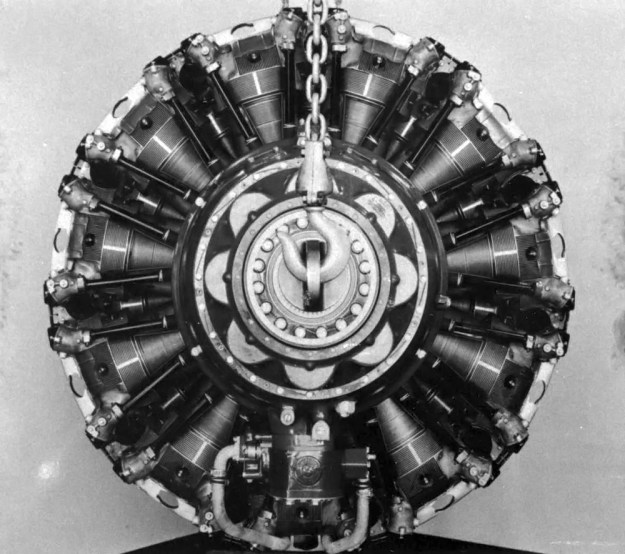

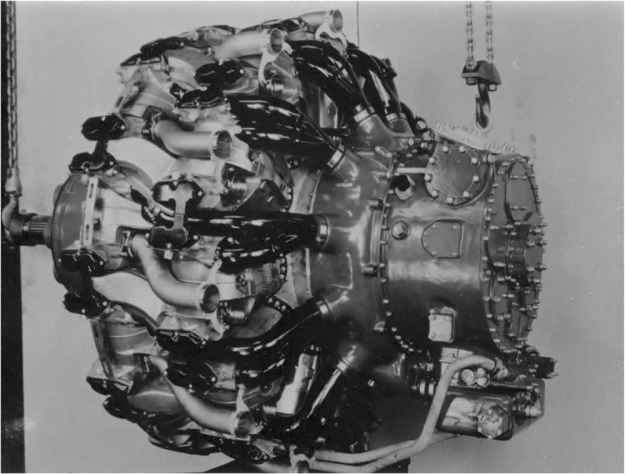

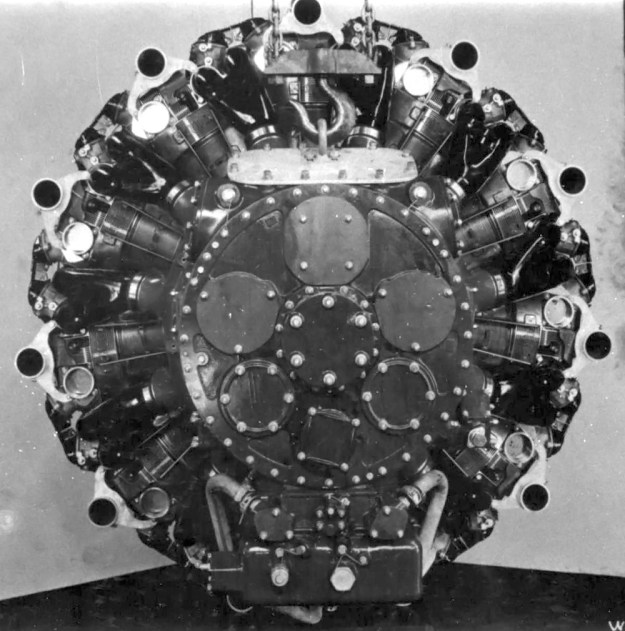

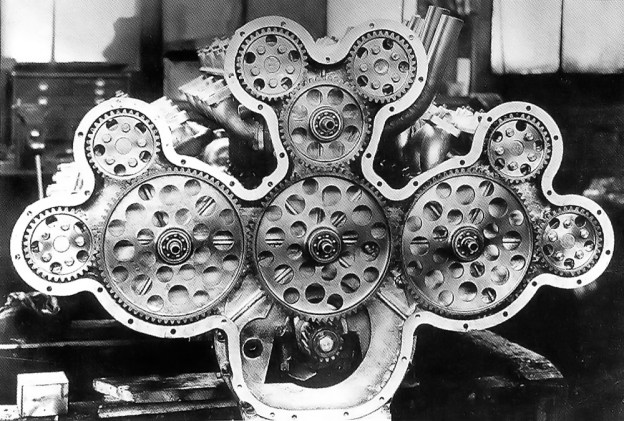

From the start, Martin had wanted a Rolls-Royce Merlin engine for the MB2, but none were available to the Martin-Baker Company. Napier was willing to loan Martin-Baker a Dagger IIIM engine, and the MB2 was designed around that engine. The Napier Dagger was an air-cooled, 24-cylinder, vertical H engine. With a 3.8125 in (96.8 mm) bore and a 3.75 in (95.25 mm) stroke, the Dagger displaced 1,027 cu in (16.8 L). The moderately supercharged Dagger IIIM produced around 805 hp (600 kW) at 4,000 rpm for takeoff and drove a 10.5 ft (3.2 m), fixed-pitch, two-blade, wooden propeller.

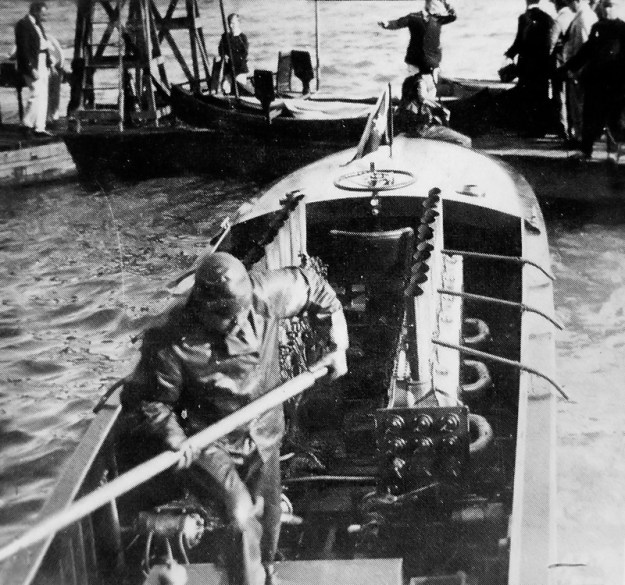

An early photo of the Martin-Baker MB2 when marked as M-B-1, with Capt. Baker at the controls. Note the exhaust manifold and how it differs from the other images.

The MB2 was designed with ease of maintenance in mind. All major components were easily accessible. The Dagger engine could be changed out faster than any other engine on any fighter then in service. Two men could remove the MB2’s armament, eight Browning .303 (7.7 mm) machine guns, in under five minutes (compared to 60 minutes for the Hurricane and 70 minutes for the Spitfire). Two men could reload the MB2, 300 rounds per gun, in 15 minutes (compared to 16 minutes for the Hurricane and 60 minutes for the Spitfire). The wings just outside of the gear could be removed in minutes to allow the aircraft to be easily transported or stored. The MB2 had a span of 34 ft (10.4 m), a length of 34 ft 9 in (10.6 m), and weighed 5,537 lb (2,512 kg). At 9,250 ft (2,820 m), the aircraft had a top speed of 305 mph (491 km/h), although some sources say 320 mph (515 km/h). The MB2’s ceiling was 29,000 ft (8,840 m).

Baker made the first flight in the MB2 on 3 August 1938. As first flown, the MB2 did not have any vertical tail. It was thought that the large main gear fairings and flat-sided fuselage would provide directional stability. The rear of the MB2’s fuselage tapered back to a vertical wedge that incorporated the aircraft’s rudder. Directional stability proved insufficient, and a small vertical tail stub was provided above the horizontal stabilizer. A conventional tail was later added to the MB2 after flight trials at Martlesham Heath in late 1938 indicated further improvement in directional stability were needed.

The MB2 with the revised small stub tail to provided better directional control over the original design having no tail. However, this tail configuration was still insufficient.

Early on, the MB2 carried “M-B-1” on the side of its fuselage for reasons that have not been made clear. While at Martlesham Heath, the MB2 was loved by ground crews for its ease of maintenance and serviceability. However, pilots found it lacking directional control, with insufficient rudder authority and heavy aileron control. Because of the control difficulties, it would not have made a good gun platform.

After the tail was modified to address the directional instability, the aircraft was re-evaluated at Martlesham Heath in late 1939. The new rudder was found to be satisfactory and effective, but the other flight controls still needed improvement. Designs were also made to fit the MB2 with fully retractable gear and change out the machine guns for cannons. But these changes were not pursued.

The Martin-Baker MB2 in flight with the final tail configuration. Note the opening for the oil cooler on the left main gear fairing and the exhaust ports on the cowling.

The Air Ministry purchased the MB2 in July 1939, but it was clear that there would be no further modifications or any chance of a production contract. While the MB2’s shortcomings could have been addressed, it would not have changed the fact that the aircraft was developed for a fighter specification over five years old. However, Martin-Baker was tasked to take what they had learned from the MB2 and develop a new Napier Sabre-powered fighter, which would become the MB3. The sole MB2 was scrapped in 1944. Designed and built by a small company with fewer than 40 employees, the MB2 exemplified simple and inexpensive construction techniques employed on an aircraft that was designed for ease of serviceability and whose performance could match fighter aircraft then in service.

From left to right, Captain Valentine Baker, James Martin, and Francis Francis, who provided funding for the Martin-Baker Aircraft Company, stand next to the MB2.

Sources:

– “Martin-Baker Fighters,” by Bill Gunston, Wings of Fame Volume 9 (1997)

– The British Fighter Since 1912 by Francis K. Mason (1992)

– Interceptor Fighters for the Royal Air Force by Michael J.F. Bowyer (1984)

– British Piston Aero-Engines and Their Aircraft by Alec Lumsden (1994/2003)

– http://www.martin-baker.com/about/mb1-mb5