By William Pearce

After John Rhodes Cobb made a small fortune as a fur broker, he started auto racing. Early in Cobb’s racing career, he served as a riding mechanic for Ernest Eldridge and his FIAT Mephistopheles racer, and he occasionally drove John Godfrey Parry-Thomas’ Babs racer on the Brooklands raceway in Surrey, England. In the late 1920s, Cobb had established himself as a capable, gentleman racer at Brooklands. His cars were often serviced by Thomas at his shop, located at the Brooklands raceway. The company was formed by Thomas and Ken Thomson, and renamed Thomson & Taylor in 1927, with Ken Taylor joining the firm after the death of Thomas during a Land Speed Record attempt.

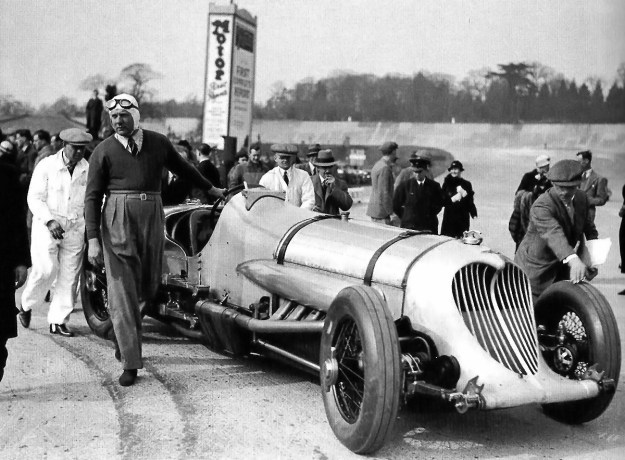

John Cobb sits behind the wheel of the Napier-Railton at the Brooklands track. The exhaust system with mufflers was a requirement for Brooklands and did a good job of muting the engine. Note the vertical bars covering the radiator.

In late 1932, Cobb ordered a special car from Thomson & Taylor that would be able to set lap records at Brooklands as well as establish endurance records up to 24 hours, with sustained speeds in excess of 150 mph (241 km/h). Cobb had previously set the Outer Circuit lap record at Brooklands three times, and it was a record that was special to Cobb. Cobb and Thomson & Taylor gave the task of designing the car to Reid Antony Railton, head engineer. Railton knew he would need to come up with a design that was strong, durable, and reliable to stand up to the rough Brooklands track and the prolonged endurance runs. The car Railton designed would be known as the Napier-Railton.

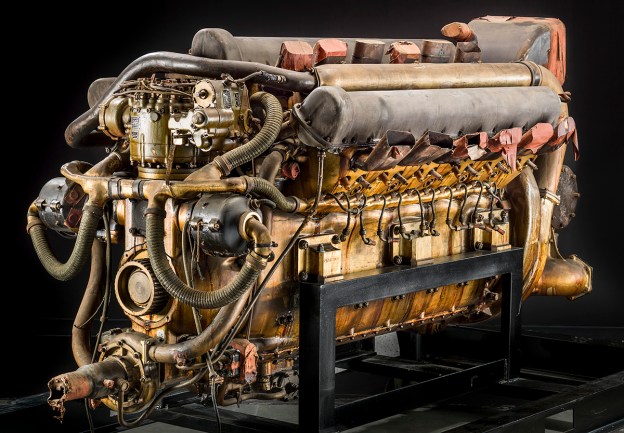

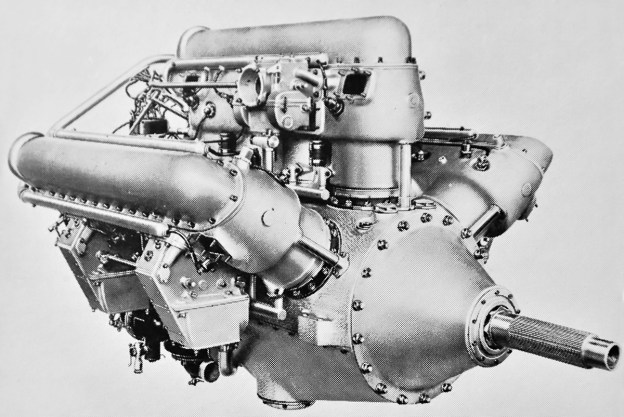

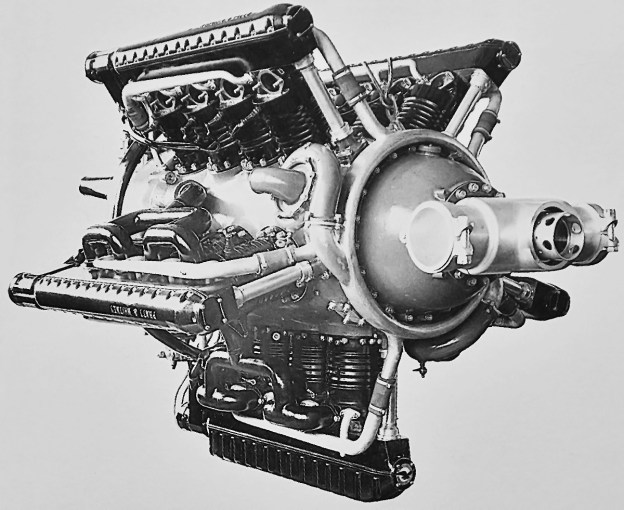

In selecting an engine for the new racer, Railton wanted something that was powerful and reliable—a high-performance engine capable of running at high-power for 24 hours. Railton selected the normally aspirated Napier Lion XIA. The Lion was a 12-cylinder aircraft engine with three banks of four cylinders. The center bank extended vertically from the crankcase, with the left and right banks angled at 60 degrees from the center bank. Normally fitted with a propeller gear reduction, the Lion XIA for the Napier-Railton was modified by Napier with a special, elongated crankshaft and the removal of the gear reduction. As tested by Napier, the special Lion XIA produced 502 hp (374 kW) at 2,200 rpm, 564 hp (421 kW) at 2,350 rpm, and 590 hp (440 kW) at 2,700 rpm. The engine was fitted at the front of the car and mounted between the chassis’ two large frame rails, which were 10 in (254 mm) tall. Five cross members secured the car’s frame.

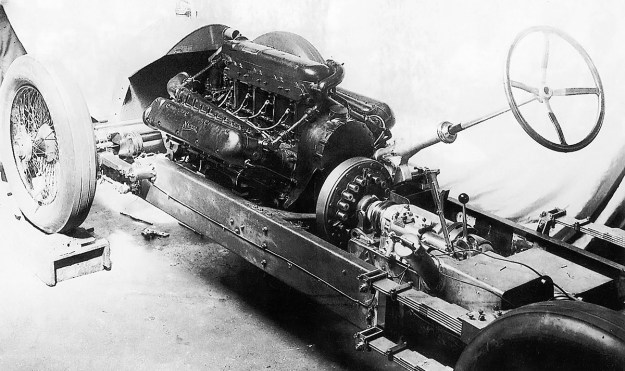

The chassis of the Napier-Railton with its Napier Lion engine and three-speed transmission. The two levers by the transmission were for the gear shift and driveshaft brake. The oil tank can be seen extending below the driveshaft and under what would become the cockpit.

Behind the engine was a single-plate clutch and the three-speed transmission. Since the car was to operate almost entirely at high speed, the first and second gears were much weaker than the robust third gear. This enabled the transmission to be smaller and lighter. The transmission drove the rear axle’s very strong differential, which had a 1.66 drive ratio. The forged rear axle housing was made of three sections: a center section that carried the differential, and left and right sections that carried the full-floating axle shafts. An oil sump, finned for cooling, was attached to the bottom of the axle’s center section. The car’s front and rear axles were positioned above the underslung frame rails, which enabled the car to have a low center of gravity. The suspension for the front axle used half-elliptical leaf springs, and the suspension for the rear axle used two sets of cantilever leaf springs on both sides of the car. The Napier-Railton was fitted with drum brakes on the rear axle and no brakes on the front axle. A driveshaft brake was operated by a hand lever and acted as a parking brake.

The chassis was covered by an aluminum body made by Gurney Nutting Ltd. The radiator at the front of the car was encased by the body, with a large opening for cooling air. At various times, the radiator opening was covered with vertical bars, a single bar, or no bars at all. The engine cowling had large humps for the left and right cylinder banks, a louvered top, and was secured by leather straps. Exhaust gases from each of the three cylinder banks were collected into separate manifolds, with the manifold for the center bank located on the left side of the car. An exhaust system consisting of a muffler and tailpipe extending to the rear of the car could be attached to each manifold. This system was used when the car competed at the Brooklands track. An undershield covered the bottom of the chassis.

At 6 ft 3 in and around 240 lb, Cobb was one of the few that could make the large Napier-Railton look almost normal-size by comparison. The leather straps that secured the engine cowling passed through the humps covering the left and right cylinder banks.

The cockpit was behind the engine and offset to the right, with the driver’s feet to the right of the transmission. The throttle pedal was in the center, with the brake pedal on the right and the clutch pedal on the left. A raised scuttle panel and windscreen protected the driver. At times, an enlarged scuttle and a shield to the cockpit’s right rear were added to protect the driver from a burst tire. In addition, a covered mirror was occasionally fitted to the scuttle left of the cockpit. An 18 US gallon (15 Imp gal / 68 L) oil tank was positioned to the left of the cockpit. The tank extended under the driveshaft and below the driver’s seat, and its underside was finned for cooling. Behind the cockpit, the body of the car tapered to a short wedge. Housed behind the driver was a 78 US gallon (65 Imp gal / 295 L) fuel tank. The Napier-Railton had a 10 ft 10 in (3.30 m) wheelbase, a track of 5 ft (1.52 m), and was 15 ft 6 in (4.72 m) long. The car weighed approximately 5,000 lb (2,268 kg). Various tire sizes ranging from 19 x 7 in (483 x 178 mm) to 35 x 6 in (889 x 152 mm) were used throughout the car’s career, with smaller tires used for acceleration and larger tires fitted for top speed. The wheels were mounted to the car with knock-off hubs. For long record runs, the throttle could be held open via a cable, and lights could be added to the car. Push starting was employed to bring the Napier-Railton’s Lion engine to life.

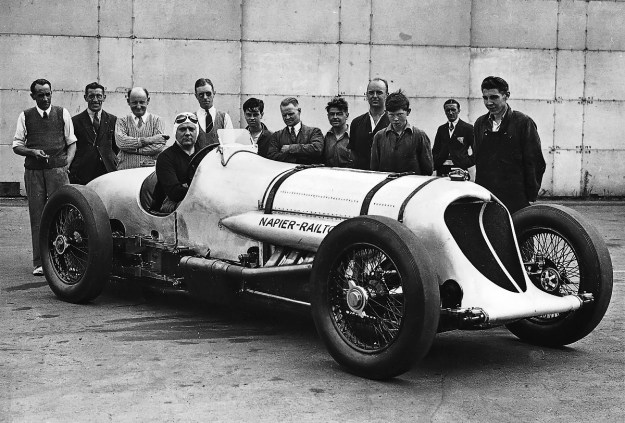

The newly completed Napier-Railton made its debut for the press on 6 June 1933. Minor testing by Cobb and Railton occurred before the debut, and serious testing was carried out in July. The car’s public debut was at the Brooklands track on 7 August 1933. Cobb set a Brooklands standing start lap record on the first lap of the Napier-Railton’s first race, covering the 2.75-mile (4.43-km) course at an average of 120.59 mph (194.07 km/h). The Napier-Railton went on to win the short race.

A builder and team photo of the Napier-Railton at Brooklands. Cobb is in the driver’s seat; Ken Taylor is on the far left; Ken Thomson is third from left; Reid Railton is fourth from left. Note the single vertical bar on the radiator housing.

Cobb then took the Napier-Railton to the 1.58-mile (2.55-km) speed ring at the Autodrome de Linas-Montlhéry track south of Paris, France for an attempt on the 24-hour record. Over 6 and 7 August 1933, American Ab Jenkins had established a new 24-hour record of 117.821 mph (189.615 km/h) driving a Pierce-Arrow V-12 at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah. This was the speed to beat. Cobb had previously arranged to use some equipment provided by George Eyston, a friend and fellow racer who was familiar with endurance runs at Montlhéry. The Napier-Railton’s exhaust mufflers were removed, and individual stacks were used. An angled shield was added to the scuttle left of the cockpit to block the exhaust flame glare from the center bank during night running. For the 24-hour attempt, Cobb’s co-drivers were Brian Lewis, Cyril Paul, and Tim Rose-Richards. Starting the record run on 2 October 1933, the car tore through its tires, and some difficulty was experienced with changing them. Push-starting the car after pit stops was also problematic. Rules stipulated that the car needed to travel forward under its own power. After shutting the car off during a pit stop, the crew needed to push it back some distance so that it could be pushed forward and started before it reached its original stopping point. Although several records were set with the Napier-Railton, including 200 miles (322 km) at 126.84 mph (204.13 km/h), 500 miles (805 km) at 123.27 mph (198.38 km/h), and six hours at 122.62 mph (197.34 km/h), the 24-hour attempt was abandoned after the radiator developed a leak and parts of the Montlhéry circuit began to break up under the car’s relentless pounding.

Back at Brooklands, Cobb and the repaired Napier-Railton set a new standing-start mile (1.6 km) record at an average of 102.52 mph (164.99 km/h) on 31 October 1933. On 4 November, the standing-start kilometer (.6 mi) record fell at 88.521 mph (142.461 km/h). Cobb was also timed covering 1 km (.6 mi) at 143.67 mph (231.21 km/h), the fastest speed recorded at Brooklands up to that point. On 2 April 1934, the Napier-Railton established a new Brooklands Outer Circuit lap record of 139.71 mph (224.84 km/h). Later that month, the Napier-Railton was back at Montlhéry for another 24-hour attempt. Cobb was supported by co-drivers Charles Brackenbury, Freddie Dixon, and Cyril Paul. Starting on 16 April, six hours passed at an average of 123.01 mph (197.97 km/h), 12 hours at 121.19 mph (195.04 km/h), and 2,000 miles (3,219 km) at 120.71 mph (194.26 km/h). On 17 April, after 19.5 hours had elapsed, Dixon lost control of the car, hit a guardrail and wound up in an infield ditch. Dixon was unharmed, but the Napier-Railton was damaged, and the record run was over. An AMR 33 light Army tank was required to pull the heavy car from the ditch. The Napier-Railton racer returned to the Thomson & Taylor works where it was repaired. At Brooklands on 6 August 1934, Cobb won the Championship Race and set a new Outer Circuit lap record at 140.93 mph (226.77 km/h).

Cobb takes flight as the Napier-Railton transitions over the River Wey to the Railway Straight and Brooklands. The bridge over the river created a bump that caused faster cars to become airborne, an indication of how Brooklands was a rough track. The image illustrates both the enlarged scuttle and the rear shield added to protect the driver. Note the bar-less radiator housing.

In mid-August 1934, Jenkins increased the 24-hour record to 127.229 mph (204.756 km/h). Cobb still wanted to set his own 24-hour record, and Jenkins’ success on the 10-mile (16-km) circular track in the wide expanses of the Salt Flats convinced Cobb to make the trip to Bonneville in mid-1935. For the Bonneville record attempt, a 120 US gallon (100 Imp gal / 455 L) fuel tank with two filler necks replaced the 78 US gallon (65 Imp gal / 295 L) tank, and the side panels covering the engine were removed for additional cooling. Like at Montlhéry, individual exhaust stacks were used.

Cobb, his team, and the Napier-Railton arrived at Bonneville in early July 1935. Ever the sportsman, Jenkins had a lot of equipment already setup on the Salt Flats and left it there for Cobb to use. On 12 July 1935, Cobb established a new 1-hour record at 152.70 mph (245.75 km/h) and a 100-mile (161 km) record at 152.95 mph (246.15 km) while testing the car on the salt. Backed by co-drivers Charlie Dodson and Rose-Richards, Cobb and the Napier-Railton set 16 records over 15 and 16 July 1935. The average speed for 500 miles (805 km) was 147.66 mph (237.64 km/h); 1,000 miles (1,609 km) was 144.93 mph (233.24 km/h); 12 hours was 139.84 mph (255.05 km/h); 2,000 miles (3,219 km) was 137.86 mph (221.86 km/h); 3,000 miles (4,828 km) was 134.56 mph (216.55 km/h); and 24 hours was 134.85 mph (217.02 km/h). In that 24-hour period, the Napier-Railton covered 3,236 miles (5,208 km).

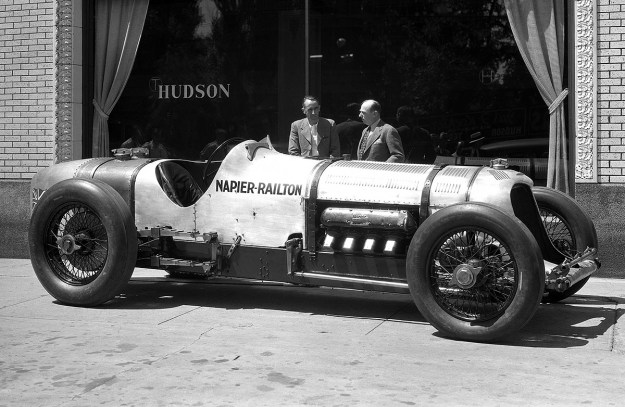

The Napier-Railton in front of Gus F. Koehler’s Hudson dealership in Salt Lake City in 1935. The Hudson Motor Car Company provided courtesy vehicles to Cobb and his team. In its Bonneville configuration the Napier-Railton had a larger fuel tank, individual exhaust stacks, and its engine side covers removed. American and British flags were painted atop the radiator housing. The anti-glare shield appears in place on the left side of the car, but the windscreen is missing.

While Cobb achieved his goal, the record did not stand for long. At the end of August 1935, Jenkins increased the 24-hour record to 135.580 mph (218.195 km/h), covering 3,354 miles (5,398 km) in his new Duesenberg Special. In mid-September, the record was broken again at Bonneville, this time by George Eyston in Speed of the Wind, averaging 140.52 mph (226.15 km/h) and covering 3,372 miles (5,427 km). In three months, three groups of racers in three separate cars established three new 24-hour records, which varied by less than six mph.

After returning to England, Cobb and Rose-Richards won a 500-mile (805-km) race at Brooklands on 22 September 1935. The Napier-Railton averaged 121.28 mph (195.18 km/h), a speed that would not be bettered in a 500-mile (805-km) race until the 1949 running of the Indianapolis 500. On 7 October 1935, Cobb and the Napier-Railton set a final lap record at Brooklands of 143.44 mph (216.36 km/h). This speed was not exceeded before the track was partially torn up during World War II. During the attempt, Cobb covered 1 km (.6 mi) at 151.97 mph (244.57 km/h), the fastest speed recorded at Brooklands.

Cobb starting an attempt for the 1-hour record in 1936. The electric starting motor can be seen just before the rear tire. The driver would pull the lever that pressed the roller against the tire. The electric motor would then be turned on, driving the entire car forward. With a little bit of speed, the clutch could be let out, forcing the ever-reliable Lion engine to turn over and fire.

In mid-July 1936, Eyston increased his 24-hour record with an average speed of 149.096 mph (239.947 km/h), covering 3,578 miles (5,759 km). Cobb had already planned to make another attempt on the 24-hour record. By early September 1936, Cobb was back in Bonneville with Brackenbury, Johnny Hindmarsh, and Rose-Richards as his co-drivers. The Napier-Railton had a new external electric starting motor that, when engaged, drove the right rear tire to effectively push-start the car. Also, an exhaust manifold (without mufflers) was fitted to the center bank to reduce the glare from the flames at night. On 10 September, using the 12-mile (19-km) course, Cobb set a new 1-hour record at 167.69 mph (269.87 km/h) and covered 100 miles (161 km) at 168.59 mph (271.32 km/h). On 12 and 13 September, the Napier-Railton established four new records, including averaging 156.85 mph (252.43 km/h) over 1,000 miles (1,609 km), 149.27 mph (240.23 km/h) over 2,000 miles (3,219 km), and 150.16 mph (241.66 km/h) over 24 hours, covering 3,604 miles (5,800 km). Cobb’s new 24-hour record was less than one mph faster than the previous record set by Eyston; once again, the record did not stand for long. In late September 1936, Jenkins took back many of the records and averaged 153.823 mph (247.554 km/h) for 24 hours, covering 3,692 miles (5,942 km).

The Napier-Railton raced only at Brooklands in 1937. On 29 March, it won a race averaging 136.03 mph (218.92 km/h), the fastest race ever run at Brooklands. On 18 September 1937, Cobb, co-driver Oliver Bertram, and the Napier-Railton won a 500 km (311 mi) race averaging 127.05 mph (204.47 km/h). This was the last time the car was run on the track. Cobb retired from circle-track racing to focus attention on his Land Speed Record (LSR) car, the twin-Lion powered Railton. Eyston and Jenkins continued their duel for endurance records, and Eyston tried for absolute LSR records with his Thunderbolt car. The Napier-Railton was stored through World War II and acted as an LSR car for the 1951 film Pandora and the Flying Dutchman. Installed for the film were a streamlined radiator housing, a headrest behind the cockpit, and an elongated tail.

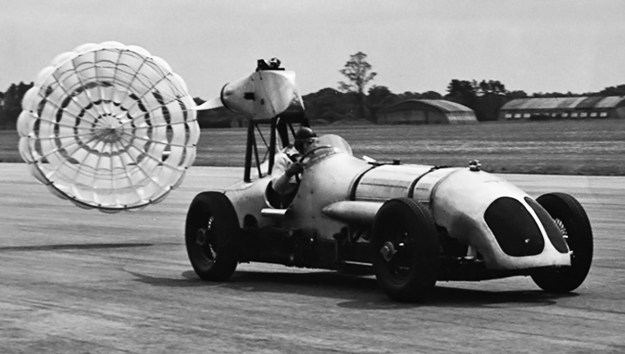

The Napier-Railton being utilized by the GQ Parachute Company to test aircraft braking parachutes. The pylon atop the rear of the car could automatically retract the parachute and store it for reuse. The streamlined nose was made for the 1951 film Pandora and the Flying Dutchman and was removed in the mid-1950s.

After Cobb’s death while attempting a water speed record in September 1952, the Napier-Railton was used by Geoffrey Quilter of the GQ Parachute Company. The car remained mostly as it had appeared in the movie, but a smaller fuel tank was fitted, and a parachute testing structure was mounted above the rear axle. To improve stopping, discs replaced the drum brakes on the car’s rear axle. Quilter used the car for a number of years to test aircraft braking parachutes. Eventually, the original radiator housing replaced the movie nose.

The Napier-Railton was purchased by Patrick Lindsay in 1961. Lindsay competed in various Vintage Sports Car Club meets and other events, and was clocked at 165 mph (266 km/h) in the Napier-Railton. After Lindsay passed, the Napier-Railton was acquired by Bob Roberts in 1971. The car was restored to a configuration similar to how it appeared while being raced at Brooklands by Cobb. After Robert’s death, the car was purchased by Victor Gauntlett in 1987 and was subsequently acquired at auction by a German collector in July 1991. Following a protracted three-year negotiation, the Napier-Railton returned to England under the ownership of Lukas Hüni in early 1997. Under an agreement with the Brookland Society, Hüni held the car until funds could be raised to purchase the Napier-Railton for the Brooklands Museum. The car’s purchase was finalized in December 1997, and the Napier-Railton was officially handed over to the Brooklands Museum on 6 May 1998. The Napier-Railton, still equipped with its original engine, is on display at the Brookland Museum and is occasionally run for special events. Over its career, the Napier-Railton set seven records at Brooklands, 11 records at Montlhéry, and 29 records at Bonneville.

The Napier-Railton in its current form enjoying some sun. The car has been mostly returned to how it appeared for its various runs at Brooklands and is occasionally run at special events. (Dave Rogers image via Wikimedia Commons)

Sources:

– Reid Railton: Man of Speed by Karl Ludvigsen (2018)

– Brooklands Giants by Bill Boddy (2006)

– The 1933 24-litre Napier-Railton, Profile Publications Number 28 by William Boddy (1966)

– Napier: The First to Wear the Green by David Venables (1998)

– The Fast Set by Charles Jennings (2004)

– The John Cobb Story by S. C. H. Davis (1953)

– Napier: Lions at Large 1916 – 2016 by Alan F. Vessey (2016)

– “King of Brooklands: The ex-John Cobb Napier-Railton Impressions” by Don Vorderman, Automobile Quarterly Volume IX, Number 1 (Fall 1976)