By William Pearce

In 1932, the Wedell-Williams Air Service Model 44 established itself as one of the premier air racers. The Model 44 was a fast, sleek monoplane with fixed gear. The aircraft was designed by Jimmie Wedell, an experienced pilot and air racer. The Weddell-Williams company was founded in 1929 when Jimmie Wedell and his brother Walter gained the financial backing of millionaire Harry Williams. Operating out of Patterson, Louisiana, Wedell-Williams Air Service was established to provide a wide range of aeronautical services that included constructing new aircraft, flight instruction, and passenger and mail service. The best way to prove one’s aircraft design abilities and gain publicity was to create a record breaking air racer—the Model 44 was exactly that. However, progress in aviation was swift, so it was in 1933 that Wedell began to design his next racer: the Model 45.

The Model 45 followed the Wedell-Williams design concept that was so well executed in their Model 44 racer. It was a simple concept: a big engine in a sleek airframe resulting in a fast aircraft.

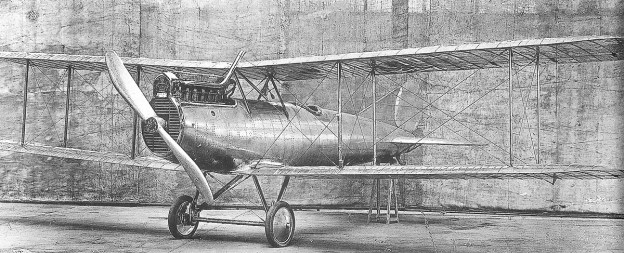

The Model 45 followed the same conventional layout as the Model 44, but the aircraft was further refined with a cantilever wing and retractable undercarriage. The Model 45 consisted of a welded chrome-molybdenum steel tube fuselage. The front and tail of the aircraft were skinned in aluminum. Fabric covered the rest of the fuselage, from in front of the cockpit back to the tail. The Model 45’s wing had a wooden spar; the rest of the structure was made from metal and skinned with aluminum. The main gear retracted inward to be fully enclosed within the wing. The aircraft’s tail skid retracted into the fuselage. Each side of the cockpit had a plexiglass panel that could slide up to fully enclose the pilot.

The Model 45 had a 26 ft 8.5 in (8.1 m) wingspan and was 24 ft long (7.3 m). The aircraft had a race weight of around 3,000 lb (1,360 kg). The Model 45 was intended to have a 14-cylinder Pratt & Whitney (P&W) R-1535 Twin Wasp radial engine of 825 hp (615 kW), and its top speed was anticipated to be over 300 mph (483 km/h). However, the R-1535 engine was not ready, so a nine-cylinder P&W R-985 Wasp Jr. engine of 535 hp (399 kW) was installed in its place.

This photo of the Model 45 was taken shortly after the aircraft was built in Patterson, Louisiana in 1933. Note the smooth cowling covering the R-985 engine. Jimmie Wedell stands by the side of the aircraft.

Wedell took the Model 45 (registered as NR62Y) up for its first flight on 28 June 1933. The R-985 engine caused the aircraft to be underpowered and tail-heavy. Very little flight testing was accomplished because Wedell had entered the Model 45 in the Bendix Trophy Race, which was scheduled for 1 July. The 1933 race was run from New York to Los Angeles. Departing for New York, Wedell made it from Patterson, Louisiana to Atlanta, Georgia (about 500 miles / 805 km) before he turned back. Wedell decided the aircraft would not be competitive with its current engine. Instead, he flew a Model 44 (No. 44) and finished the race in second place, behind Roscoe Turner in his Wedell-Williams Model 44 (No. 2).

With the R-1535 still delayed, a nine-cylinder, 800 hp (597 kW) P&W R-1340 Wasp Sr. engine was installed on the Model 45 in place of the smaller engine. The R-1340 provided sufficient power for the aircraft and restored its proper balance. While the two engines used the same mounts, the R-1340 had a larger diameter than the R-985 and required a new cowling. The smooth cowling covering the R-985 engine was replaced by a larger cowling with bumps around its diameter to provide clearance for the engine’s rocker covers. The same engines were used in the Model 44, so the entire engine package (including cowling) could be swapped between the aircraft. An 8 ft 2 in (2.5 m) diameter, variable-pitch propeller was also installed.

The Model 45 with its R-1340 engine installed. Note the bumps on the cowling that provided clearance for the engine’s rocker covers. The engines used in the Model 45 and Model 44 (No. 44) racer were interchangeable.

The Model 45 made its race debut at the Pan American Air Races held during the dedication of Shushan Airport (now New Orleans Lakefront Airport) in February 1934. Wedell flew the Model 45 to a new speed record over a 100 km (62 mi) course, averaging 264.703 mph (425.998 km/h), with the fastest lap over 266 mph (428 km/h). Wedell reported that he flew the distance at less than full power.

After the record run, Wedell-Williams Air Service began work to prepare their aircraft for the 1934 Bendix and Thompson Trophy Races, respectively scheduled for 31 August and 4 September. But disaster struck on 24 June 1934; Jimmie Wedell was killed when the de Havilland Gypsy Moth he was piloting crashed shortly after takeoff. Wedell was with a student pilot but had control of the aircraft. The student escaped with only minor injuries. The loss of head designer Jimmie Wedell was a major blow to Wedell-Williams Air Service, but the company continued to plan for the upcoming races.

Experienced Wedell-Williams pilot John Worthen flew the Model 45 in the Bendix Trophy Race from Los Angles, California to Cleveland, Ohio. Worthen led the race, followed by Doug Davis flying Wedell-Williams Air Service’s other racer, a Model 44 (No. 44). Worthen, in the Model 45, had a comfortable lead when he became lost and overflew Cleveland by 100 miles (160 km). Worthen landed and refueled in Erie, Pennsylvania and then flew to Cleveland; he landed 36 minutes behind Davis. Had he not overflown Cleveland, Worthen and the Model 45 would have easily won the Bendix race; the trip to Erie added over 50 minutes to his total time. Even with the delay, the Model 45 had averaged 203.213 mph (327.040 km/h) in the Bendix Trophy Race.

In the Shell Speed Qualification heat (Group 3) for the Thompson Trophy Race, Worthen and the Model 45 placed third at 292.141 mph (470.156 km/h), coming in behind the Model 44 racers of Davis (No. 44) at 306.215 mph (492.805 km/h) and Roscoe Turner (No. 57) at 295.465 mph (475.505 km/h). In the Shell Speed Dash Unlimited race, Worthen and the Model 45 achieved 302.036 mph (486.080 km/h).

The size and weight of the Wedell-Williams Model 45 was more suited for cross-country racing than pylon racing. It would have won the 1934 Bendix race had it not been for a navigation error. The Model 45 is barely an aviation footnote since it was flown fewer than two years and never won a major race.

The Wedell-Williams Air Service team decided that the Model 44 (No. 44) had the greatest potential for the Thompson Trophy Race. This decision was made because of some instability the Model 45 exhibited in the pylon turns—perhaps because the aircraft was not fully refined due to Wedell’s death. The team had been swapping the R-1340 and R-985 engines between racers for various events, and now the R-1340 engine was installed in the Model 44 for the Thompson Trophy Race. The Model 45 would not be competitive with the R-985 engine, and it was withdrawn from the race.

During the Thompson Trophy Race, Davis and the Model 44 were comfortably in the lead when he cut a pylon. He went back to circle the pylon when the aircraft either stalled or experienced a structural failure. The Model 44 smashed into the ground, killing Davis instantly. The shocked Wedell-Williams Air Service team disassembled the Model 45 and shipped it back to Paterson; it never flew again.

Wedell-Williams Air Service was never able recover because tragedies continued to plague the company. On 18 July 1935, Walter Wedell and his passenger were killed in a crash while flying in a Brewster Aristocrat. On 19 May 1936, Harry Williams and John Worthen were killed in a crash after the engine in their Beech Staggerwing quit shortly after takeoff.

The Model 45 at the National Air Races in Cleveland, Ohio in September 1934. The unfortunate death of Jimmie Wedell seemingly cut short the aircraft’s development, and the Model 45 never reached its true potential. Its predecessor, the Model 44, continued to race until 1939, the last year of the races until after World War II.

The Model 45 was donated to Louisiana State University in 1936, but what happened to it is not known. It was most likely scrapped at some point. A full-scale replica Model 45 is in the Wedell-Williams Aviation and Cypress Sawmill Museum in Patterson, Louisiana.

Early in 1934, the Army Air Corps expressed interest in the Model 45 design suitably modified into a military pursuit aircraft. Initially, the Wedell-Williams Air Service proposal was rejected, but a subsequent proposal was approved, and a contract was issued on 1 October 1935 for detailed design work. The Wedell-Williams Air Service fighter was designated XP-34. The XP-34 had a wingspan of 27 ft 9 in (8.5 m) and a length of 23 ft 6 in (7.2 m). The 4,250 lb (1,928 kg) aircraft was forecasted to have a top speed of 286 mph (460 km/h) with a 750 hp (559 kW) P&W R-1535 or 308 mph (496 km/h) with a 900 hp (671 kW) P&W R-1830. The design of the XP-34 progressed until the aircraft was cancelled after the death of Williams in 1936, by which time its performance had been surpassed by other fighters.

The Wedell-Williams Model 45 replica in the Wedell-Williams Aviation and Cypress Sawmill Museum in Patterson, Louisiana. (Steffen Kahl image via Flickr)

Sources:

– Wedell-Williams Air Service by Robert S. Hirsch and Barbara H. Schultz (2001)

– Aircraft of Air Racing’s Golden Age by Robert S. Hirsch and Ross N. Hirsch (2005)

– The Golden Age of Air Racing Pre-1940 by S. H. Schmid and Truman C. Weaver (1963/1991)

– They Flew the Bendix by Don Diggins (1965)

– Racing Planes and Air Races 1909-1967 by Reed Kinert (1967/1969)

– http://www.crt.state.la.us/louisiana-state-museum/online-exhibits/louisiana-aviation-since-1910/jimmie-and-walter-wedell/