By William Pearce

In 1823, Thaddeus Fairbanks and his brother Erastus founded the E & T Fairbanks Company, which operated an iron foundry. In June 1832, Thaddeus patented the platform scale which quickly became the mainstay of the company. Back then, scales were integral to business as marine and railway shippers charged by weight. The E & T Fairbanks Company became the leading scale manufacturer in the United States and sold thousands of scales in the US, Europe, South America, and China.

In the 1870s, Charles Morse, an E & T Fairbanks Company distributor, was responsible for adding Eclipse Windmills and pumps to the E & T Fairbanks Company product list. Morse’s successful sales abilities enabled to him becoming a partner, and the company was eventually renamed Fairbanks Morse & Company.

In the late nineteenth century, Fairbanks Morse & Company continued to expand its now very diverse product line. The Company began producing oil and naptha engines in the 1890s. The Fairbanks Morse gas engine became a success providing power for irrigation, electricity generation, and oilfield work. Small power plants built by Fairbanks Morse were popular and evolved by burning kerosene in 1893, coal gas in 1905, and semi-diesel in 1913.

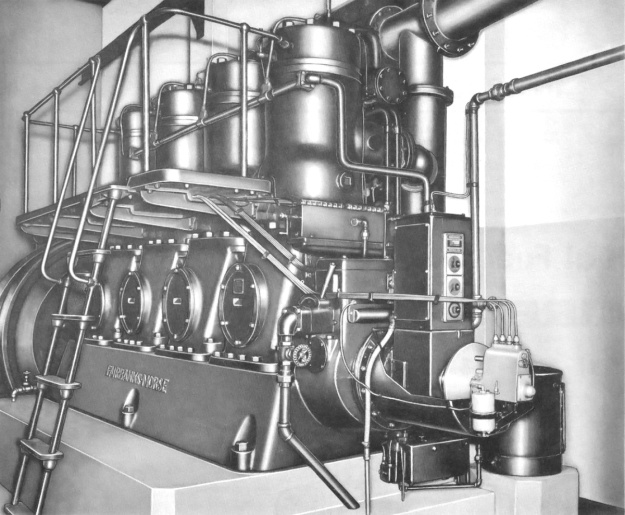

After the expiration of Rudolf Diesel’s American license in 1912, Fairbanks Morse entered the large engine business. Introduced in 1914, the company’s large Model Y semi-diesel stationary engine became a standard workhorse used by sugar, rice, and timber mills; mines, and other applications. The Model Y was available in sizes from one through six-cylinders, or 30 to 200 horsepower (22 to 149 kW).

Successor to the Model Y, the Y-VA engine was developed in Beloit, Wisconsin and introduced in 1924. It was the first high compression, cold start, full diesel developed by Fairbanks Morse without the acquisition of any foreign patent. The Y and Y-VA engines were made to run for long periods without stopping. By 1925 there were over 1,000 American cities generating electricity with Fairbanks Morse engines.

Around 1925 the Y-VA diesel was improved and renamed the Model 32 engine. The Model 32 was the culmination of many years of improvement upon the initial Model Y design. The improvements included various cylinder head designs, increased compression, and the eventual adoption of high-pressure injection and differential fuel injectors. To differentiate various cylinder heads and methods of induction on the Model 32 engine series, letter designations A thru E were used.

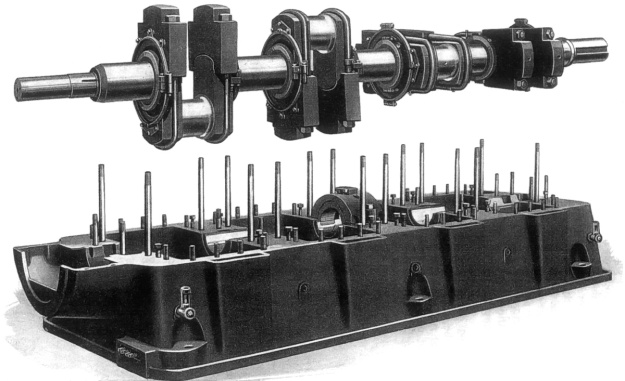

The crankshaft and lower base for a four-cylinder 32E engine. The base for the individual cylinders mounted directly to the lower base.

The Model 32 was available in two cylinder sizes: 12 in (305 mm) bore with a 15 in (381 mm) stroke and 14 in (356 mm) bore with 17 in (432 mm) stroke. The 12×15 engine, known as -12, was available in one- through three-cylinder versions with each cylinder displacing 1,696 cu in (27.8 L) and producing about 40–50 hp (30–37 kW). The 14×17 engine, known as -14, was available in one- through six-cylinder versions with each cylinder displacing 2,617 cu in (42.9 L) and producing 60–75 hp (45–56 kW). Normal operating speed ranged from 257 to 360 rpm.

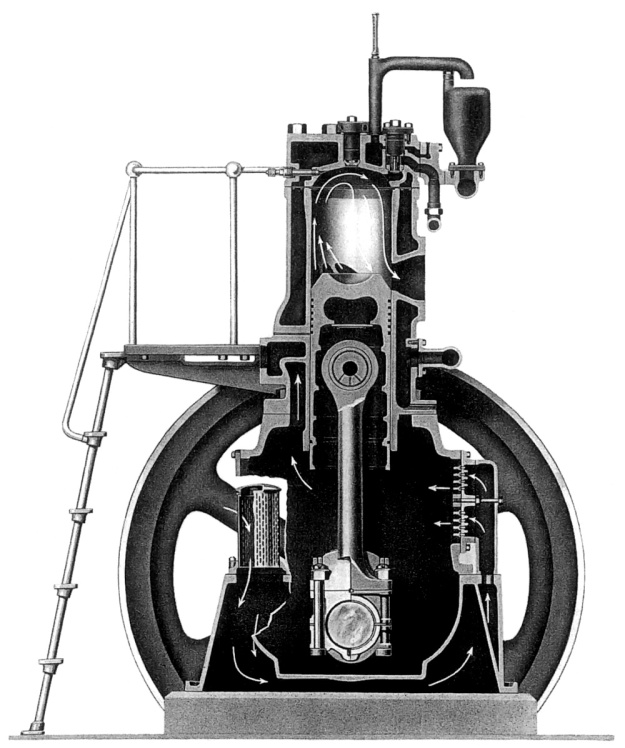

The two-stroke, water-cooled diesel of all cast iron construction was air started with 250 psi (17.2 bar). The only moving parts in the Model 32 were the pistons, connecting rods, crankshaft, oil pumps, fuel pumps, flywheel, and governor. The engine had no intake or exhaust valves. Air was drawn through the crankcase and into the cylinder when the piston uncovered an induction port. The air was then compressed by the piston as fuel was injected into the cylinder at 2,000 psi (137.9 bar) and ignited by the heat of the 500 psi (34.5 bar) compression. As the piston moved down on the power stroke, it uncovered the exhaust port, allowing the burnt gases to be expelled. Fuel consumption was around 0.39 lb/hp/hr (237 g/kW/h).

The Model 32 engines were in service for years in power stations, manufacturing plants, ice plants, flour mills, rock crushing plants, cotton gins, seed oil mills, textile mills, irrigation and drainage pumping stations, and many other locations. To give some idea of the service life of the engine, at 10,000 hours of operation the needle rollers on the piston pin should be replaced. At 20,000 hours the needle rollers should be replaced again and the piston pin should be rotated 180 degrees. At 40,000 hours, or 4.57 years of continuous operation, the piston pin and bushing should be replaced. The Model 32 was built at least into the 1940s. A number of engines were still in regular service at various locations into the 1970s, with at least one being run until 1991. The Indian Grave Drainage District in Quincy, Illinois still has three operational Model 32 engines, and three engines are on standby as back-up power generators in Delta, Colorado.

Today, stationary diesels are still used for power generation, pumping, and other purposes. Fairbanks Morse still exists in this field and also manufactures marine and locomotive diesels. As far as the Model 32 is concerned, some still exist in abandoned factories and power stations, while others have been saved and preserved. A few Model 32s are run for special events, enabling them to shake the ground once again.

Here is a video of 1936 four-cylinder Fairbanks Morse 32D-14 by accessgainer8. This engine is owned and occasionally operated by the Pottsville Historical Museum near Grant’s Pass, Oregon. The engine weighs around 60,000 lb (27,216 kg), and the flywheel alone weighs about 12,000 lb (5,443 kg).

Sources:

– Fairbanks Morse: 100 Years of Engine Technology by C. H. Wendel (1993)

– https://old.oldtacomamarine.com/fairbanks/manual.html

– https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairbanks-Morse

– http://www.oldtacomamarine.com/engines/fairbanks/index.html