By William Pearce

In 1944, Yakovlev sought to achieve higher performance from its Yak-3 fighter by installing a Klimov VK-108* engine. The standard Yak-3 was originally designated Yak-1M and designed in 1942 as a lightweight Yak-1. When this new aircraft entered production in 1943, it was redesignated Yak-3, taking the designation used for an earlier fighter prototype (the I-30) that did not enter production. Thus, Yak-3 production followed that of the Yak-7 and Yak-9 fighters.

The Yak-3 VK-108 built in the closing days of World War II was the fastest Soviet piston-powered aircraft. Note the heat-resistant panels behind the exhaust stacks and the inlet for the supercharger under the engine. The upper row of exhaust stacks can just be seen.

The Yak-3 was a maneuverable fighter that incorporated everything the Yakovlev team had learned by producing its previous fighter aircraft. The fuselage was of metal construction and covered by duralumin from the cockpit forward, with plywood covering the rear fuselage. The aircraft’s wings had duralumin spars and wooden ribs and stringers. The wings were skinned with plywood that was covered with doped fabric. The Yak-3’s control surfaces consisted of a duralumin frame covered with fabric. The standard Yak 3 was powered by a VK-105PF2 engine producing 1,290 hp (962 kW) for takeoff and 1,240 hp (925 kW) at 6,890 ft (2,100 m) altitude.

The VK-105 engine can trace its origin back to the 750 hp (559 kW) M-100 engine of 1935, which was a licensed-built Hispano-Suiza 12Ybrs. However, many changes had been implemented by the time VK-105 production began in 1939. For example, the M-100 had a single-stage, single-speed supercharger, a 5.91 in (150 mm) bore, and two valves per cylinder. The VK-105 had a single-stage, two-speed supercharger, a 5.83 in (148 mm) bore, and three valves per cylinder.

Constructed under the supervision of lead designer Vladimir Klimov, the VK-105 was a liquid-cooled, V-12 engine with provisions for firing a cannon through the propeller hub. With its 5.83 in (148 mm) bore and 6.69 in (170 mm) stroke, the engine had a total displacement of 2,142 cu in (35.1 L). Each cylinder bank had a single overhead camshaft that actuated the two intake valves and single exhaust valve. The engine’s intake and exhaust ports were located on the outer sides of the engine. The intake manifold for each cylinder bank incorporated three carburetors. The VK-105 had a compression ratio of 7.1 to 1.

This three-view drawing of the Yak-3 VK-108 shows that even with the cockpit moved aft 15.75 in (.40 m), the aircraft was very similar to a standard VK-105-powered Yak-3.

The ideal standard production Yak-3 had a top speed of 404 mph (650 km/h) at 14,108 ft (4,300 m) and 354 mph (570 km/h) at sea level. The aircraft could climb to 16,404 ft (5,000 m) in 4.2 minutes—averaging 3,906 fpm (19.8 m/s). The Yak-3 had an empty weight of 4,641 lb (2,105 kg) and a loaded weight of 5,864 lb (2,660 kg). The aircraft had a 20 mm cannon that fired through the propeller hub and two 12.7 mm machine guns mounted above the engine (the post-war Yak-3P was fitted with three 20 mm cannons).

It was on the standard Yak-3 platform that a VK-108 engine was substituted to create an aircraft of much higher performance. The VK-108 engine was a further evolution of the basic M-100 design, but by this time in its design history, the VK-108 had little in common with the original M-100 engine. The VK-108 was closely related to the VK-107 engine from which it was directly derived.

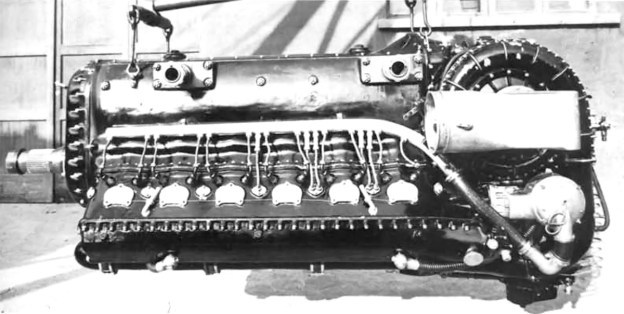

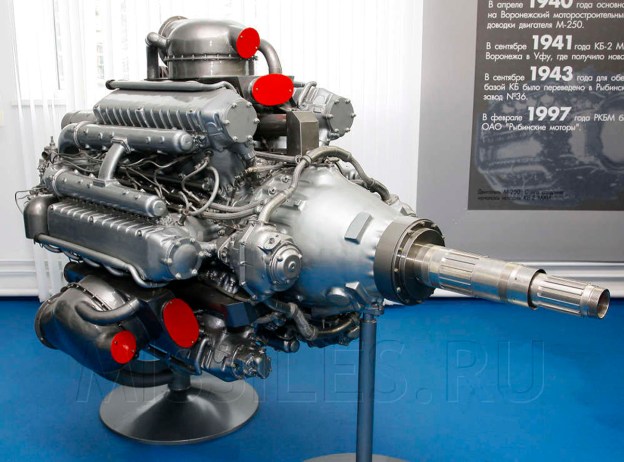

With the exception of the VK-107 engine, the VK-108 differed from previous Klimov engines by having new induction and exhaust systems, a new valve train with two intake and two exhaust valves per cylinder, strengthened components for increased rpm and power, an improved gear reduction, and increased boost via a redesigned supercharger drive. The VK-108 retained the 5.83 in (148 mm) bore, 6.69 in (170 mm) stroke, and 2,142 cu in (35.1 L) total displacement of previous Klimov engines.

Pictures of a Klimov VK-108 engine are hard to come by. Seen here is a VK-107A engine which was very similar to the VK-108. Note the silver induction manifold along the outer side of the engine. The yellow linkages are for the three carburetors. The remaining four intake runners provide air only into the cylinders. The exhaust manifolds in the Vee of the engine are missing; the VK-107 used six-into-one manifolds while the VK-108 used individual exhaust stacks. (Mike1979 Russia image via Wikimedia Commons)

The most unusual features of the VK-108 engine were its intake and exhaust systems and the function of its four valves per cylinder. Pressurized air from the single-stage, two-speed supercharger flowed through an intake manifold located on the outer side of each cylinder bank. Each intake manifold had seven intake runners that led to the cylinder head. Four of the runners provided air only; the remaining three runners had individual carburetors to supply the air/fuel mixture to the cylinders. The first runner supplied just air to the first cylinder. The second runner provided the air/fuel mixture to the first and second cylinders. The third runner supplied just air to the second and third cylinders. The fourth runner provided the air/fuel mixture to the third and fourth cylinders. The fifth runner supplied just air to the fourth and fifth cylinders. The sixth runner provided the air/fuel mixture to the fifth and sixth cylinders. The seventh runner supplied just air to the sixth cylinder. So each carburetor supplied air/fuel for two cylinders; the engine had a total of six carburetors.

The two intake valves were positioned in tandem on the cylinder’s centerline. One intake valve in each cylinder opened to let supercharged air into the cylinder while the other intake valve opened to bring in the air/fuel mixture from a carburetor. The air intake valve opened 65 degrees before and closed after the air/fuel intake valve. This allowed the supercharged air to scavenge the cylinder and also aid in its cooling.

One exhaust valve was positioned on the outer side of the engine, and the other exhaust valve was on the Vee side. This configuration meant that there were separate exhaust ports on each side of the cylinder head. The VK-108 engine had one row of six exhaust stacks on the outer side of the cylinder bank and one row of exhaust stacks on the Vee side of the cylinder bank. The complete engine had four rows of six exhaust stacks.

Basic drawing of the Klimov VK-108 valve arrangement. A single overhead camshaft acted directly on the intake valves and actuated the exhaust valves via a follower.

A single overhead camshaft was used with three lobes for each cylinder. The center lobe acted on a follower that actuated both exhaust valves. One of the other lobes actuated the fresh air valve, and the last lobe actuated the air/fuel mixture valve. This arrangement allowed for the completely different valve timing and duration of the two intake valves.

The VK-108 was cleared for up to 8.5 psi (0.6 bar) of boost and had a compression ratio of 6.75 to 1. The engine produced 1,850 hp (1,380 kW) at 3,200 rpm for takeoff, 1,650 hp (1,230 kW) at 4,921 ft (1,500 m), and 1500 hp (1,119 kW) at 14,764 ft (4,500 m). The VK-108 weighed 1,731 lb (785 kg).

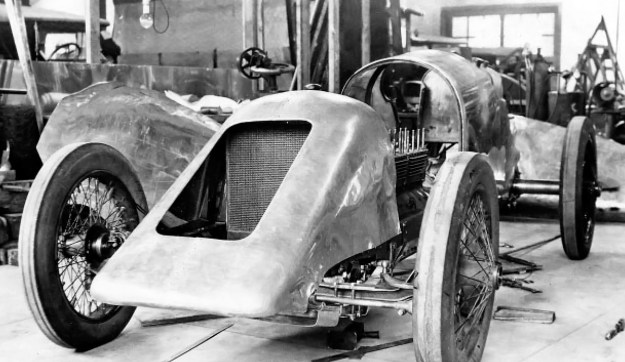

The installation of the VK-108 engine necessitated some changes of the Yak-3 airframe. Built under the supervision of A. N. Kanookov, the Yak-3 VK-108 had a new radiator, oil cooler, and propeller installed. A new cowling was constructed to accommodate the two additional rows of exhaust stacks. Heat-resistant panels were added behind each of the four rows of exhaust stacks. The cowling also omitted the ports for the two machine guns which were deleted from the Yak-3 VK-108. The supercharger air inlet was relocated under the engine, and the aircraft’s ailerons were skinned in duralumin rather than fabric. Because of the heavier engine, the cockpit was moved 15.75 in (.40 m) aft to keep the aircraft’s center of gravity within limits.

The VK-108-powered Yak-3’s first flight was on 19 December 1944 with Viktor L. Rastorgooyev at the controls. The aircraft had a wingspan of 30 ft 2 in (9.2 m), a length of 28 ft 1 in (8.55 m), an empty weight of 5,251 lb (2,382 kg), and a loaded weight of 6,385 lb (2,896 kg). With no armament and a light fuel load, the Yak-3 VK-108 achieved a top speed of 463 mph (745 km/h) at 20,636 ft (6,290 m), making it the fastest piston-powered Soviet aircraft. The aircraft also exhibited a phenomenal climb rate, reaching 16,404 ft (5,000 m) in 3.5 minutes—averaging 4,687 fpm (23.8 m/s). The Yak-3 VK-108 had a service ceiling of 34,121 ft (10,400 m).

The upper exhaust stacks are well illustrated in this rear view of the Yak-3 VK-108. The aircraft had excellent performance, but the engine was not reliable.

Although the Yak-3 VK-108’s performance was very good, fight testing the aircraft was difficult because of engine issues. The VK-108’s high rpm and boost resulted in constant overheating problems. Vibration issues and excessive smoke were also encountered. The problems were so severe that flight testing was halted on 8 March 1945, with the aircraft only accumulating 1 hour and 17 minutes of flight time.

A second VK-108-powered Yak-3 was built in late 1945 under the supervision of V. G. Grigor’yev. This aircraft was reportedly armed with a 20 mm cannon that fired through the propeller hub and an additional 20 mm cannon mounted above the engine and offset to the left—each gun had 120 rounds of ammunition. A new radiator with additional surface area was installed to prevent overheating issues. However, engine trouble persisted. Despite its excellent performance, the Yak-3 VK-108 project was abandoned in favor of more reliable piston aircraft and jets.

*The Soviet Union changed some aircraft engine designations from starting with an “M” to starting with the designer’s initials. In 1944, the M-105 engine became the VK-105; the M-107 became the VK-107; and the M-108 became the VK-108—VK standing for Vladimir Klimov, the engine’s lead designer. The VK designation was used throughout this article for simplicity.

By 1945, it was clear that future fighter aircraft would be jet-powered, and there was no need to continue the development of the VK-108 engine.

Sources:

– Yakovlev Fighters of World War II by Yefim Gordon, Sergey and Dmitriy Komissarov (2015)

– Russian Piston Aero Engines by Vladimir Kotelnikov (2005)

– Hispano Suiza in Aeronautics by Manuel Lage (2004)

– Yakovlev Aircraft since 1924 by Bill Gunston and Yefim Gordon (1997)

– Yakovlev Piston-Engined Fighters by Yefim Gordon and Dmitriy Khazanov (2002)

– http://www.airpages.ru/mt/m107_klimov.shtml