By William Pearce

In the early 1900s, the Roberts Motor Company of Sandusky, Ohio made a series of two-stroke engines for boats. With aviation gaining popularity, it was only natural for the company to adapt its engines for aircraft use. Roberts aircraft engines first appeared in 1911 and were designed by the company’s founder and president Edmund W. Roberts.

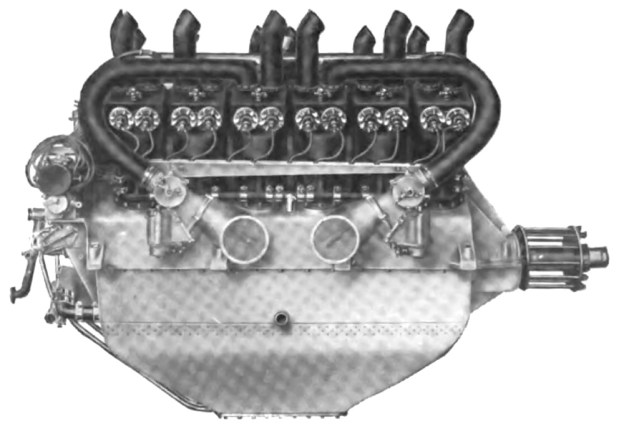

A four-cylinder Roberts 4-X engine on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC. Note the tubular housing to which the carburetor is attached. Inside the housing is the tubular distributor sleeve for delivering the air/fuel mixture to the cylinders. The water pump is mounted on the upper rear of the housing. (National Air and Space Museum image)

Roberts Motor Company’s aircraft engines differed from their marine counterparts in that they were engineered to be as light as possible. To keep parts (and associated points of failure) to a minimum, the Roberts two-stroke engines did not use poppet valves. In addition, Roberts’ engines incorporated unique designs to overcome drawbacks generally found with two-stroke engines, namely the air/fuel mixture pre-igniting as it entered the cylinder, causing a backfire.

The engines’ cast cylinder liners were constructed of a proprietary alloy called “Aerolite,” which Roberts said was as light as aluminum but twice as strong and had the wear properties of cast iron. The individual cylinder liners were covered by an aluminum water jacket. A ring around the base of the cylinder liner would fit into a recess around the bottom of the water jacket, securing the two together. The cylinder liner’s spark plug boss (and that of the decompressor if present) passed through the water jacket casting. The outer diameter of the boss was threaded, and a nut secured the top of the water jacket and cylinder liner. This nut would also draw up the base of the liner into the water jacket, securing the whole cylinder assembly.

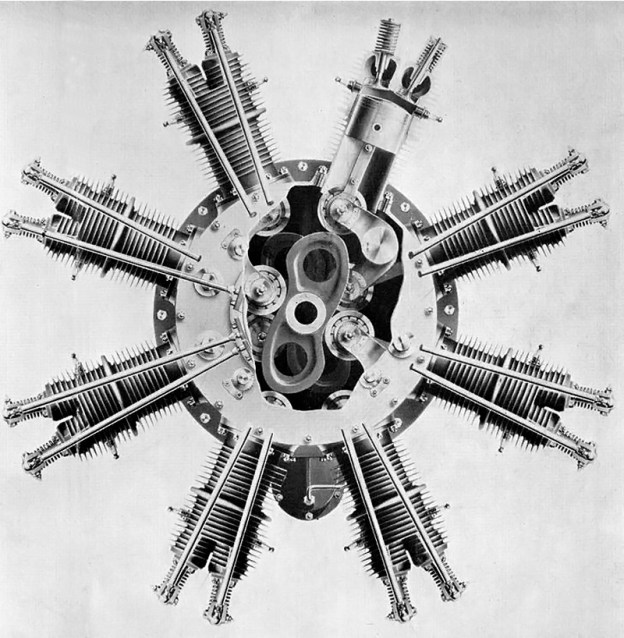

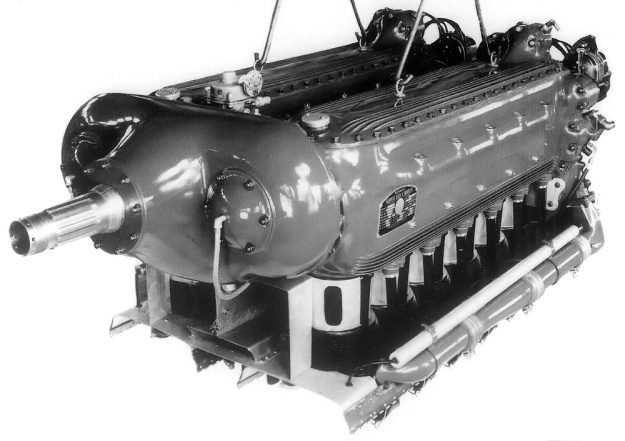

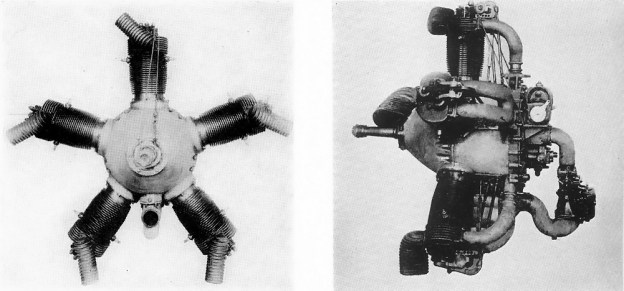

The six-cylinder Roberts 6-X engine. The crankcase casting provided a space under each cylinder for the air/fuel mixture. Each space was sealed by crankshaft main bearings. Note the two exhaust ports for each cylinder.

The pistons were made of cast iron and were attached to drop forged I-beam connecting rods made of vanadium steel. The connecting rods were attached to the crankshaft by a bronze strap about a third the size of the crankpin. (Firing every revolution, the pistons of a two-stroke engine are not pulled down by the crankshaft and therefore do not need a full-size connecting rod bearing cap.) The crankshaft was hollow and made of drop forged steel. The cylinders were secured to the crankcase by four bolts, with adjacent cylinders sharing their bolts. The crankcase was made from Magnalium, an aluminum and magnesium alloy that made it lighter and stronger than an aluminum crankcase of the same thickness.

The carburetors were mounted to a tubular housing that ran along the right side of the engine. Inside of this housing was a tubular distributor sleeve (also called a rotary induction valve) driven by an intermediate gear that engaged the accessory drive gear mounted on the end of the crankshaft. The distributor sleeve rotated at crankshaft speed and had ports to control the air/fuel mixture flow from the carburetor into the crankcase. The crankcase was constructed so that a small space existed under each cylinder for the incoming charge. The carburetor aligned with multiple ports in the distributor sleeve to allow a constant flow into the distributor, but each cylinder matched up with a single port to control air/fuel delivery. For each cylinder, the incoming charge passed from the distributor though a port in the side of the crankcase. The distributor helped eliminate the risk of backfires and distributed the air/fuel mixture equally to all the cylinders, allowing the engine to run smoothly.

The tubular distributor sleeve of a Roberts 4-X engine. The ports at the center of the tube aligned with the carburetor.

The distributor port opened as the piston moved up and drew in the air/fuel mixture. The port then closed as the piston moved down on its power stroke, compressing the incoming charge underneath. Two ports in the piston aligned with ports in the cylinder wall when the piston was near bottom dead center. This alignment allowed the pressurized, incoming air/fuel mixture to flow from the crankcase into a space on the outer side of the cylinder. In this space, Roberts installed what they called a “cellular by-pass” to prevent backfires. The incoming charge flowed through the cellular by-pass and then through another set of ports positioned above the piston. The piston’s top had a large deflector to send the incoming air charge toward the top of the combustion chamber to improve exhaust gas scavenging. This deflector was positioned on the intake port side of the piston. Two exhaust ports were located on the opposite side of the cylinder from the intake ports and were also controlled by the piston so that all ports were uncovered when the piston was near bottom center.

The cellular by-pass was a series of flat and corrugated plates creating a honeycomb mesh. The large surface area of the cellular by-pass extinguished any flame should a backfire occur, but it did not decrease the engine’s efficiency in normal operation. The Roberts engine’s resistance to backfiring allowed a leaner mixture to be used, thus increasing the engine’s fuel economy. The cellular by-pass also helped mix and vaporize the fuel in the incoming charge.

Various parts for one of the two Roberts 6-X replica engines built for Kermit Weeks. Note the deflector on the top of the pistons and the two ports in the side of the pistons. A decompressor valve can be seen on the top of the cylinder in the lower left corner. (Fantasy of Flight image)

The water pump was mounted at the right rear of the engine and was driven from the gear driving the tubular distributor sleeve. The pump drew water from the radiator and then pushed it through a passageway on the right side of the crankcase. Each cylinder had an open port that aligned with a coolant passageway in the crankcase. The water flowed into a small channel in the cylinder and then around the exhaust ports and up into the cylinder’s water jacket. It then flowed out the top of the cylinder and into a manifold that led back to the radiator. The engine was lubricated by the oil and fuel mixing and via splash lubrication. Grease cups were used to lubricate the main bearings.

A single spark plug was mounted in the center of each cylinder’s semi-hemispherical combustion chamber. The spark plug was fired by a Bosch magneto mounted at the rear of the engine. The magneto was driven by a helical gear via the intermediate gear that meshed with the accessory drive gear on the end of the crankshaft. An advance fork mounted above the magneto shaft moved the helical gear of the magneto along its shaft to either advance or delay ignition—an adjustment that could be made by the pilot while in flight.

The exposed accessory gears of the Robert 6-X replica. The crankshaft drove an intermediate gear, the backside of which engaged the magneto drive shaft. To advance or delay the timing, the helical gear for the magneto drive shaft could be adjusted by the brass advance fork above it. The intermediate gear drove the gear for the tubular distribution sleeve, which in turn drove the gear for the water pump. (Fantasy of Flight image)

The Roberts four-cylinder engine was known as the 4-X. It had a 4.5 in (114 mm) bore, a 5 in (127 mm) stroke, and a total displacement of 318 cu in (5.2 L). The engine produced 50 hp (37 kW) at 1,200 rpm. It used one carburetor, and its magneto turned at twice crankshaft speed. Its crankshaft was 2.5 in (64 mm) in diameter, with crankpins 1.75 in (44 mm) in diameter and 2.5 in (64 mm) long. The crankshaft was supported by five main bearings; the one toward the propeller was 6.375 in (162 mm) long. The crankshaft was 40 in (1,016 mm) long and weighed 17.5 lb (7.9 kg). The 4-X was 40.5 in (1.03 m) long, 25 in (.64 m) tall, 24 in (.61 m) wide, and weighed 170 lb (77 kg).

The six-cylinder engine was known as the 6-X. Like the 4-X, it had a 4.5 in (114 mm) bore and a 5 in (127 mm) stroke. The engine’s total displacement was 477 cu in (7.8 L), and it produced 75 hp (56 kW) at 1,200 rpm. The 6-X used two carburetors, and its magneto turned at three times crankshaft speed. Its crankshaft and crankpins were the same size as the 4-X’s. The crankshaft was supported by seven main bearings, was 52 in (1,321 mm) long, and weighed 27.5 lb (12.5 kg). The 6-X was 52.5 in (1.33 m) long, 25 in (.64 m) tall, 24 in (.60 m) wide, and weighed 240 lb (109 kg).

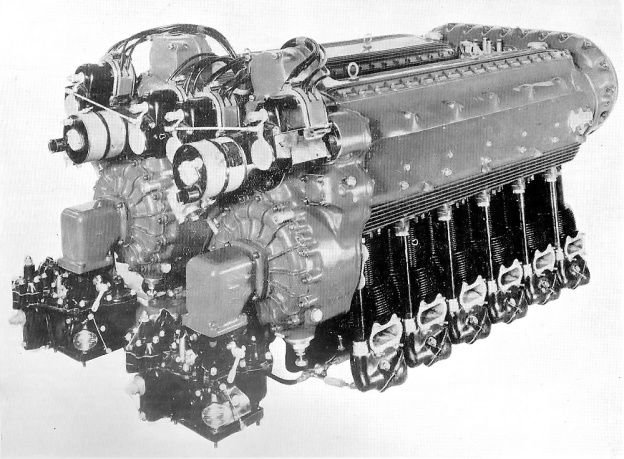

A further development of the six-cylinder engine was the 6-XX. This engine had its accessory gears covered and bathed in oil. Its bore and stroke were enlarged to 5.5 in (140 mm) and 6 in (152 mm) respectively. The 6-XX’s total displacement was 588 cu in (14.0 L), and it produced 125 hp (93 kW) at 1,100 rpm. The engine used two carburetors. Its Bosch HL magneto turned at 1.5 times crankshaft speed to fire one of the two spark plugs in each cylinder. The other spark plug was fired by a Delco distributor. The 6-XX’s crankshaft was 3 in (76 mm) in diameter, with crankpins 2.5 in (64 mm) in diameter and 3.5 in (99 mm) long. The crankshaft was supported by seven main bearings; the one toward the propeller was 12 in (305 mm) long. The 6-XX was approximately 60.5 in (1.54 m) long, 27.5 in (.70 m) tall, 24 in (.60 m) wide, and weighed 390 lb (177 kg).

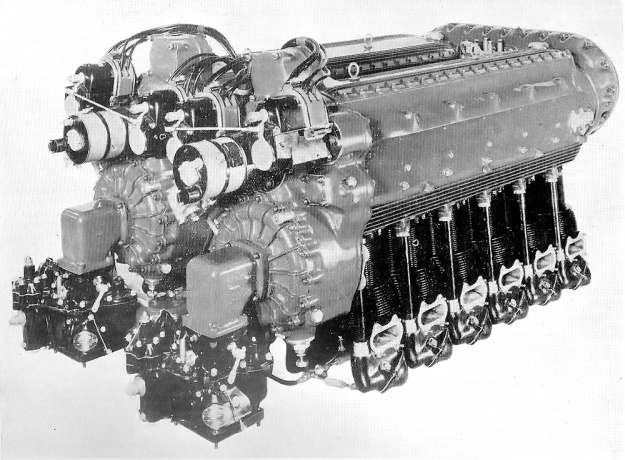

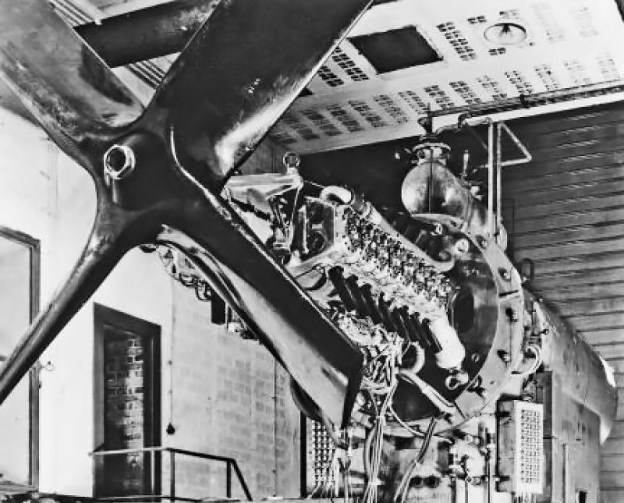

The Roberts engines were refined over time and used by a good number of early aviation pioneers. By 1913, all Roberts engines had the exposed accessory gears enclosed like those on the 6-XX engine. This change necessitated the magneto be repositioned. The cylinder liners were now made of cast iron, and the water jackets were made of Aerolite. The pistons were also made of Aerolite, which reduced their weight by over 2 lb (.9 kg) each. The tubular distributor sleeve was mounted on four sets of ball bearings to reduce friction. Dual ignition, like that used on the 6-XX, was available as an option on the 6-X engine. A starting crank attached to the end of the crankshaft was also an option.

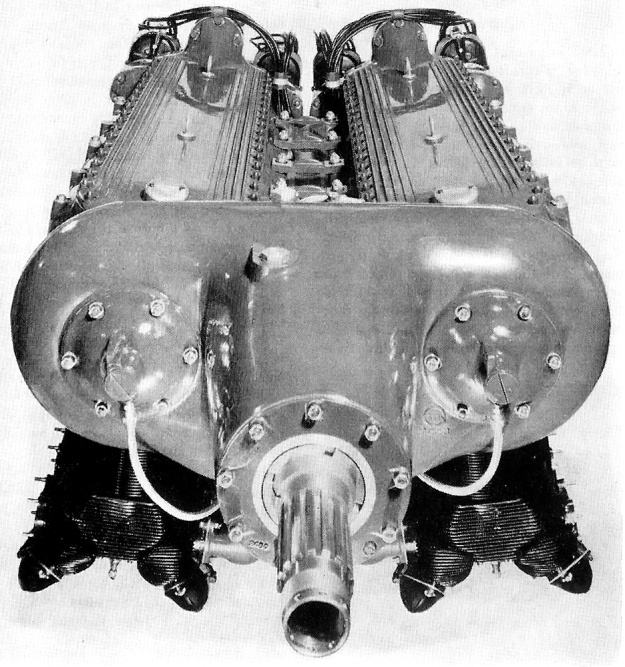

The rear of the 1913 Roberts 6-X engine showing the enclosed accessory gears, repositioned magneto, and optional hand starting crank on the end of the engine. The decompressors can be seen on the top of the cylinders. These were used to make starting the engine easier.

As two-stroke Roberts engines were surpassed by new four-stroke engines, like the Curtiss OX-5 and Hispano-Suiza 8, the company struggled to keep up. By 1918, the 6-X engine had its bore and stroke increased to 5 in (127 mm) and 5.5 in (140 mm) respectively, giving a total displacement of 648 cu in (10.6 L). The tubular distributor was replaced by more conventional intake manifolds, and the engine produced 100 hp (75 kW) at 1,200 rpm. The 6-X now weighed 368 lb (167 kg).

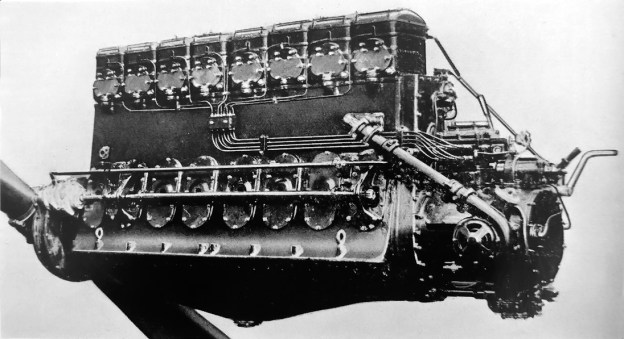

There is also some indication that a V-12 was planned and possibly constructed by Roberts in the late 1910s. This engine was known as the E-12. It had a 6 in (152 mm) bore, a 6.5 in (165 mm) stroke, and a total displacement of 2,205 cu in (36 L). The engine produced 350 hp (261 kW) at 1,200 rpm. Each cylinder had its own crankpin, and 13 main bearings supported the crankshaft. The E-12 weighed 990 lb (490 kg).

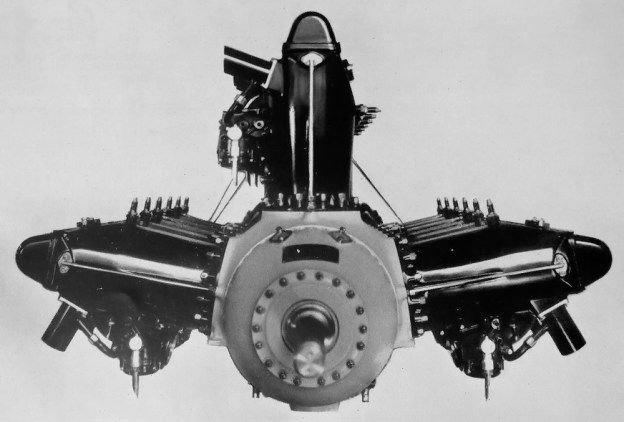

One of Weeks’ Roberts 6-X replica engines. The engines were built to power a replica Benoist XIV flying boat. The Benoist is a pusher, which is why the outlet for the coolant pipe is toward the propeller shaft. Note the brass grease cups for lubricating the crankshaft main bearings. The cover on each cylinder is for the cellular by-pass. (Fantasy of Flight image)

The Roberts Motor Company left the aviation field by 1919 to focus on marine engines. Around this time, the company changed its name to Roberts Motors. A few years later, Roberts Motors went out of business. A number of early Roberts four- and six-cylinder aircraft engines still exist in museums.

Recently, Kermit Weeks of Fantasy of Flight in Polk City, Florida commissioned the creation of two replica Roberts 6-X engines. One of the engines was a test engine, and the other would be installed in a Benosit XIV flying boat replica. An original engine was reverse engineered, allowing these engines to be built. Below is a video from 2013 of Mr. Weeks checking on the progress of the Roberts 6-X engine construction at Vintage & Auto Rebuilds in Chardon, Ohio. Both Roberts 6-X replica engines have since been completed and test run.

Sources:

– Roberts Aviation Motors by The Roberts Motor Co. (1912)

– “Construction of Cylinder of Internal Combustion Engines” US patent 1,210,537 by Edmund W. Roberts (granted 2 January 1917)

– The 1913 Model 6-X by The Roberts Motor Co. (1913)

– Fantasy of Flight Blog (various entries relating to the Roberts engine and Benoist flying boat replica)

– Aerosphere 1939 by Glenn Angle (1940)

– (Jane’s) All the World’s Aircraft 1918 by C. G. Grey (1918)