By William Pearce

John Walter Christie was born in New Milford, New Jersey on 6 May 1865. From 1881 to 1900 (age 16 to 25), he worked in and was a consultant for various engineering firms. During this time, he designed a new style of gun turret for Navy ships. This design proved lucrative, and in 1900, Christie opened his own machine shop, Walter Christie Machinery, in New York City, New York. He opened the Christie Iron Works the very next year in 1901. As the dawn of the automotive age shone on the United States, the successful Christie was able to own an automobile, but the engineer in him could not help but see ways to improve its design.

J. Walter Christie in his 1903 front-wheel drive auto, the first built in the United States. Just visible behind the rear wheel is the radiator. Christie took this car to Ormond Beach, Florida in January 1904.

By late 1903, Christie had built his own automobile, and it was unlike any other. He designed not only the car but also its engine and transmission. Christie felt that an automobile drive system should pull the vehicle (like a train or carriage), not push it (like a boat). As a result, Christie focused on a front-wheel drive system in which the engine was situated transversely between the front wheels. He believed this arrangement would create a light, simple, high-speed auto. Christie’s first vehicle design closely followed a patent that he took out in 1904. Christie’s front-wheel drive car was the first of its kind built in the United States.

The front axle of Christie’s auto was also the engine’s crankcase and housed its transmission. The cylinder block was mounted atop the axle housing. The auto had a low gear and a reverse gear; both provided a five to one reduction and enabled the drive wheels to slip relative to one another. For normal (high-speed) operation, the drive wheels were coupled to the crankshaft and wheel slip was limited. Each drive wheel had a clutch to facilitate the gear change. In addition, each drive wheel had two universal joints, and shafts that allowed for steering and independent coil spring suspension. The rear axle used leaf spring suspension.

A drawing from Christie’s 1904 patent illustrating the front-wheel drive system’s drive shafts, universal joints, and coil spring suspension. Note the offset X-beams of the connecting rods.

The 1903 car originally accommodated a driver and passenger (or mechanic, which for Christie was often his nephew Lewis Strang), but it was later fitted with a second row of seats for three passengers. The car only had rear brakes, and they were operated by a hand lever or a foot pedal. The auto weighted about 1,400 lb (635 kg). The engine for the 1903 car is believed to have had a 5.0 in (127 mm) bore and a 6.0 in (152 mm) stroke. It displaced 471 cu in (7.7 L) and produced around 30 hp (22 kW). The connecting rods were of the X-beam type. The X-beam was offset relative to the crankpin to allow for a shorter crankshaft and to provide clearance for the crankshaft’s three main bearings. A handle for crank-starting the engine protruded from the front of the axle, but the car was typically push started.

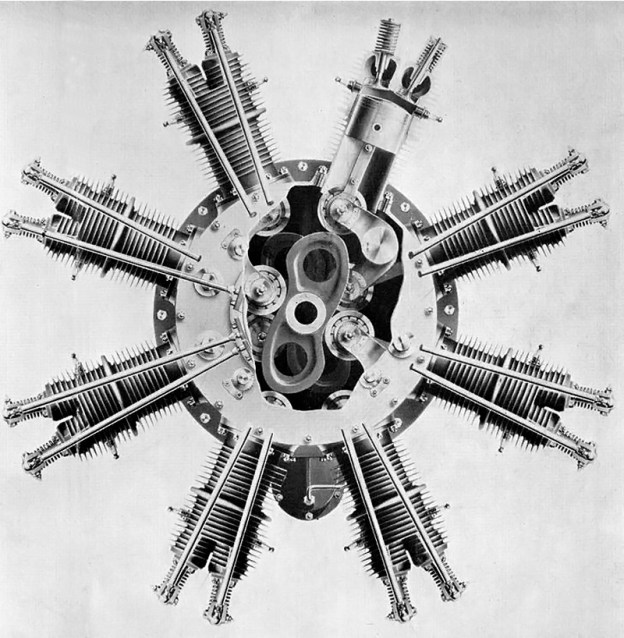

The engine had an intake over exhaust (F-head) valve arrangement. A set of four intake valves with a small combustion chamber space beneath them was positioned adjacent to the cylinder. The intake valves were atmospheric (or automatic): they were held closed by a weak spring and pulled open by the vacuum created during the piston’s downward stroke. A single, large exhaust valve was situated under the intake valves. The exhaust valves were mechanically operated. They were actuated by pushrods driven by a camshaft geared to the engine’s crankshaft. Each cylinder had a single spark plug positioned in the combustion chamber space between the exhaust valve and intake valves. The spark plugs were fired by a communicator (distributor) driven from an auxiliary shaft.

The 606 cu in (9.9 L), 30 hp (22 kW) engine of the 1903 Christie car. The spark plugs are in the center of the combustion chamber space adjacent to the cylinders. A set of four intake valves are above each spark plug, with a single exhaust valve below. Note the exhaust manifold. The hand crank on the front of the car was used to start the engine.

For induction, the air/fuel mixture flowed from a remote carburetor and through a long intake pipe to the engine. The intake manifold sat atop the engine and was split into four runners. Each runner connected to one group of four intake valves

The engine’s cylinders were covered by water jackets formed from sheet copper and screwed to the cylinder block. A remote water pump drew cooling water from the radiator and sent it to the engine. After flowing through the engine, the cooling water was taken from the top of the engine and sent to the radiator. The radiator was positioned under the rear of the car for better weight distribution. The water pump was driven from the same shaft that drove the ignition system’s communicator.

Christie’s 1904 racer with its unusual radiator and eight-intake-valves-per-cylinder engine. Christie sits in the driver’s seat.

Christie took the 1903 car to Ormond Beach, Florida (just north of Daytona Beach) in January 1904. In his car, Christie averaged 63.1 mph (101.5 km/h) in a 10 mile (16 km) race and completed a 25 mile (40 km) endurance race. However, the engine did experience some issues from lack of lubrication. Christie continued to campaign this car at a few events, but he also built a larger car more dedicated to racing in 1904.

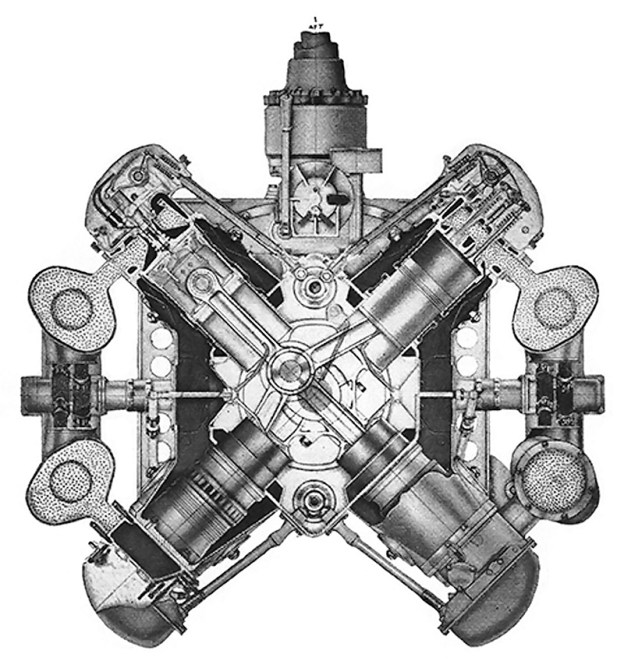

Christie’s 1904 racer used an engine of similar configuration to the 1903 engine. However, each cylinder had two sets of intake valves, for a total of eight per cylinder. The new set of four intake valves was positioned directly above the piston. Each of the four intake runners that sat atop the engine had two outlets, one for each set of four valves. The engine’s bore and stroke were 6.25 in (159 mm) and 6.75 in (171 mm) respectively. The engine had a total displacement of 828 cu in (13.6 L) and produced 70 hp (52 kW). Its crankshaft and pistons were made of carbon steel, and its crankcase and flywheels were made of a manganese bronze alloy. The spark plugs were fired from a battery powered coil ignition.

A close up of the engine in the 1904 Christie racer. Note the springs for the mechanical exhaust valves, the lack of an exhaust manifold, and the outlet for the sheet copper water jacket.

In the 1904 car, the driver and passenger were moved to the extreme rear of the vehicle for better weight distribution. In addition, the fuel tank was situated under the seat. A new radiator was installed in the middle of the auto. It consisted of around 60 long, copper tubes shaped in an inverted “U” extending from one side of the car to the other. The radiator was positioned so that air passed over it rather than through it; this configuration limited its effectiveness. No information regarding where or if the 1904 car was raced has been found. Some believe that it was a modification of the 1903 car, but it was not; the engine, axle, and frame were all different.

Christie continued to develop his concept of the front-wheel drive racer and built another car toward the end of 1904. The car, sometimes referred to as the Blue Flyer, made its debut at Ormond Beach in January 1905. It was very similar to the 1904 racer but had a new frame and axle. The car was powered by the same 70 hp, 36-valve (four being exhaust), four-cylinder engine used in the 1904 car. However, its orientation had been changed so that the exhaust valves were toward the rear of the vehicle.

The engine of the 1905 Christie racer was the same used in the 1904 racer; it was repositioned so that the exhaust valves faced toward the rear of the vehicle. The protuberance on the front of the engine was the water jacket outlet used on the 1904 car. The two sets of four valves for one cylinder are visible in the right image.

A new radiator was developed consisting of 12 sections (although photos seem to indicate only eight sections). Each of the sections was made up of eight copper tubes that were 5/16 in (8 mm) in diameter and 64 in (1.63 m) long. Attached to each section were 340 aluminum fins that were 5 in (127 mm) long and 1 in (25 mm) wide. Reportedly, this gave the radiator a surface area of some 20,000 sq in (12.9 sq m), but as with the earlier radiator, air flowed over its surface. Cooling water was taken from the water jacket between the cylinders and delivered to an expansion tank in front of the radiator. The water then flowed through the radiator and into the bottom of the water jacket on both sides of the engine. The 1905 racer had a 96 in (2.44 m) wheel base, a 57.5 in (1.46 m) track, and weighed 1,800 lb (816 kg).

For each revolution of its 40 in (1 m) wheels, the car travel 10 feet (3 m) forward. Given the car’s direct drive, 90 mph (145 km/h) would be achieved at 792 rpm. Christie raced the car on Ormond Beach in January 1905 and covered a mile in 42.2 seconds (85.3 mph / 137.3 km/h). Christie went on to win a 50 mile (80 km) race and received the Lozier Trophy. However, his was the only car to finish the race. Regardless, people were impressed by Christie and his automobiles. Based on the interest in his vehicles, Christie formed the Christie Direct Action Motor Car Company in March 1905 to manufacture passenger and race cars.

This image shows Christie’s 1905 racer modified with a second engine. The rear engine appears to be identical to the engine used in the 1903 car. The radiator appears to have eight sections.

In search of more power, Christie installed a second engine in the 1905 car. The car was lengthened, and the second engine was installed behind the driver and passenger. The second engine produced around 30 hp and powered the rear wheels. The engine appears to be the same four intake and one exhaust valve engine used in the 1903 car (and used in the 1906 car described below). The two engines provided a total of around 100 hp (75 kW). The twin-engined car made its debut on 4 July at Morris Park, New York. The car proved to be a handful but went on to run at Cape May, New Jersey in July, where it covered a mile in 37.0 seconds (97.3 mph / 156.6 km/h). In August, Christie ran a km in 25 seconds (89.5 mph / 144.0 km/h). In September, that flying km time was lowered to 23.25 seconds (96.2 mph / 154.8 km/h), for which Christie won the Cape May Trophy. Later in September, the rear engine was removed from the racer after it failed while Christie was attempting a new mile record. (It appears two additional radiator sections were added at this time, bringing the total to 10.)

Christie then set his sights on the Vanderbilt Cup race scheduled for 14 October in Long Island, New York. George Robertson was selected to drive the car in the race, but he was not familiar with the peculiarities of the car and its front-wheel drive. Robertson had trouble during qualifications on 23 September and ultimately crashed the car. The needed repairs took too long, and Christie’s car was out. However, the Cup Commission made a bizarre decision that is still not understood. Three qualified cars were removed from the race, and three cars that did not qualify were reinstated; Christie’s racer was one of the three reinstated cars.

Christie and George Robertson sit in the 1905 racer ready for a Vanderbilt Cup practice run . The rear engine has been removed, and the radiator now has 10 sections. Robertson crashed the car a short time later.

Christie worked feverishly, almost up to the start of the race, to completely repair his racer, which had suffered some engine damage. Christie drove his car in the race due to Robertson’s inexperience with the unique racer. At the start, Christie’s 1905 racer ran poorly and completed the first lap at only 29.2 mph (47.0 km/h). The engine then smoothed out, and the second lap passed at 56.0 mph (90.1 km/h). On the fourth lap, Italian driver, and race leader, Vincenso Lancia left the pits right as Christie was speeding by. Christie tried unsuccessfully to avoid a collision. Both drivers and their mechanics escaped with only minor injuries. Christie’s car was damaged beyond repair, and the time needed to repair Lancia’s car effectively took him out of contention.

Christie rebuilt the 1905 racer with a new V-4 engine. The car made its debut in January 1906. Unfortunately, it crashed on 16 September during qualification for the 1906 running of the Vanderbilt Cup. Christie quickly took stock of his resources to find a new car for the races held on 6 October.

The Christie Direct Action Motor Car Company’s 1906 touring car. This car was stripped of its body and modified to race in the 1906 Vanderbilt Cup. Note the stripe painted on the axle.

The Christie Direct Action Motor Car Company had just completed a seven-passenger touring car. With no other car available, it was the only option for the race. Christie quickly returned to his New York shop and removed the touring car’s blue painted body and black leather seats. A new body was fabricated with the seats over the rear axle. The steering was redone and the steering shaft extended. Other efforts were made to lighten the 2,300 lb (1,043 kg) touring car.

The touring car’s radiator was removed and a new one installed. The new radiator was similar to those used in the previous Christie cars but had a header tank at its center. The engine of the touring car was very similar to the original Christie F-head engine from 1903 and to the engine used in the rear of the 1905 car—all had four atmospheric intake valves and one mechanical exhaust valve. It is possible that these three engines were actually the same engine. However, the bore and stroke of the touring car’s engine was increased from the 1903 engine by .375 in (10 mm) and 1.0 in (25 mm) respectively. The touring car’s engine had a 5.375 in (137 mm) bore and a 7.0 in (178 mm) stroke. The engine produced 50 hp (37 kW) at 1,200 rpm from its 635 cu in (10.4 L). The car had a 102 in (2.59 m) wheel base and a 56 in (1.42 m) track. In race trim, the touring car’s weight was dropped to 1,895 lb (860 kg) race-ready.

Christie and his nephew Lewis Strang sit in the race-ready touring car stripped for the 1906 Vanderbilt Cup race. This image was taken at the start of an elimination trial. The stripe on the axle noted in the previous image is just visible.

At less than half the power of most of the other cars in the Vanderbilt Cup, Christie did not stand much of a chance. After running for a while in seventh place, Christie had slipped back to 13th place out of the 18 competitors, averaging 44.7 mph (71.9 km/h) when the race was called. Even so, Christie had shown that his front-wheel drive cars were as reliable and competitive as those of other manufacturers that used a conventional powertrain. After the race, Christie refocused on his V-4 racers.

Christie’s 1906 touring-car-turned-racer was eventually sold to William Gould Brokaw. The car reappeared in March 1908 at Ormond Beach, Florida and was driven by R. G. Kelsey. The racer failed to finish a 125 mile (201 km) race but placed second and averaged 62.4 mph (100.4 km/h) in a 256 mile (412 km) race held two days later. Also, Kelsey covered a mile in 42.8 seconds (84.1 mph / 135.3 km/h). The further activities and ultimate disposition of the racer is unknown.

Christie and Strang taking a turn during the 1906 Vanderbilt Cup race. Although the bore had been increased, the engine could very well be the same as the original 1903 engine.

Sources:

– “The Front-Wheel-Drives of John Walter Christie, Inventor” by Stan Grayson Automobile Quarterly Volume 14, Number 3 (1976)

– “Motor-Vehicle” US patent 761,657 by Walter Christie (granted 7 June 1904) 2.7 MB pdf

– “A New American Automobile” Scientific American (28 January 1905)

– “The First Christie Front Drive Touring Car” The Automobile (13 September 1906)

– “Now for the Selection of the American Cup Team” The Motor Way (20 September 1906)

– “Christie’s New 100-Horsepower Racer” The Automobile (5 August 1909)

– “Florida’s Meet Supplied More Records than Races” by John C. Wetmore The Automobile (12 March 1908)

– http://www.stohrdesign.com/christie-automobiles-1903-1909-a-blog (various pages)

– http://www.vanderbiltcupraces.com (various pages)