By William Pearce

In 1942, the British Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough and Supermarine Aviation were working on ways to improve the Spitfire fighter. One of the main limiting factors of the aircraft was with its wing encountering compressibility at high speed. The investigation led to interest in designing a laminar flow airfoil and adapting it to an existing Spitfire airframe. In late 1942, the British National Physics Laboratory joined the effort, and Supermarine issued Specification No 470 for the new Spitfire wing in November. As designed, the new wing was 200 lb (91 kg) lighter, would increase the aircraft’s roll rate, and was expected to increase the aircraft’s speed.

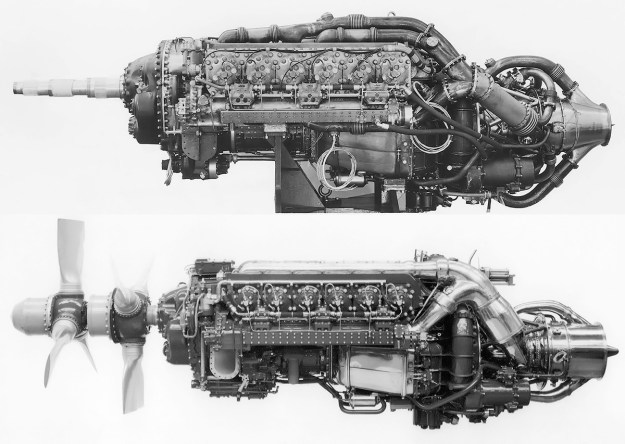

The first Supermarine Spiteful prototype (NN660) consisted of new laminar flow wings mounted to a Spitfire XIV fuselage. Note the wide and shallow radiator housings under the wings and the standard canopy

A proposal was submitted to the British Air Ministry and gathered enough interest for Specification F.1/43 to be issued in February 1943, calling for a single-seat fighter with a laminar flow wing for Air Force service and provisions for a folding wing to meet Fleet Air Arm (FAA) requirements. Supermarine proceeded with the design under the designation Type 371. Originally, the aircraft was to be named Victor or Valiant, names that were previously (but temporarily) applied to advanced Spitfire models. However, the Type 371 eventually had its name changed to Spiteful. Three prototypes were ordered, and a fourth was added later.

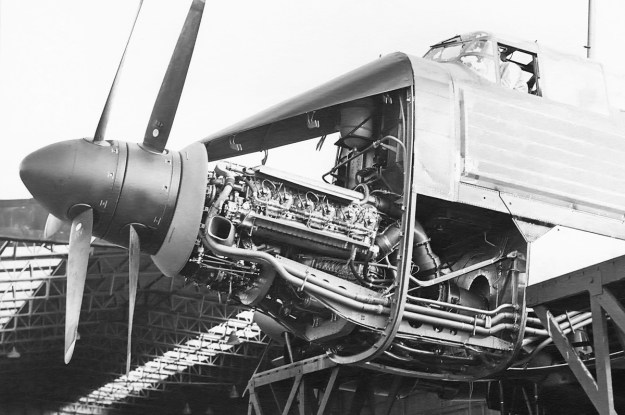

The design of the Supermarine Spiteful was overseen by Joseph Smith. The laminar flow wing was a completely new design compared to the wing used on the Spitfire. The all-metal wing had two spars and a straight taper on the leading and trailing edges, which simplified its manufacture. The skin used was relatively thick to add rigidity and improve aileron control. Unlike with the Spitfire, the landing gear retracted inward with the main wheels being housed in the comparatively thick wing roots. The landing gear struts compressed as the gear retracted to minimize the space needed within the wing. Wide and shallow radiators for engine cooling were housed behind the main gear wells. The oil cooler was positioned behind the coolant radiator in the left wing, and the intercooler radiator was positioned in front of the coolant radiator in the right wing. The radiator housings had adjustable inlets and exit flaps. Each wing had two 20 mm cannons with 167 rounds for each inner gun and 145 rounds for each outer gun. The underside of each wing could accommodate two 300 lb (136 kg) rockets or a hardpoint for a drop tank or a bomb up to 1,000 lb (454 kg).

The all-metal, monocoque fuselage of the Spiteful was similar to that of the Spitfire. The cockpit was raised to improve the pilot’s view over the aircraft’s nose. A new, sliding bubble canopy covered the cockpit. Four fuel tanks in the fuselage, forward of the cockpit, held a total of 120 gal (100 Imp gal / 455 L), and a tank in each wing root held 10 gal (8 Imp gal / 36 L). Starting with the third prototype, a 74 gal (62 Imp gal / 282 L) fuel tank was added behind the cockpit, bringing the total internal capacity to 214 gal (178 Imp gal / 809 L). Two 108 gal (90 Imp gal / 409 L) drop tanks could be carried under the wings, or a single 204 gal (170 Imp gal / 773 L) drop tank could be mounted to the aircraft’s centerline.

The Spiteful prototype (NN664) is considered the first true Spiteful because it incorporated the new fuselage. The aircraft was never painted. Note the standard, Spitfire F.21 tail.

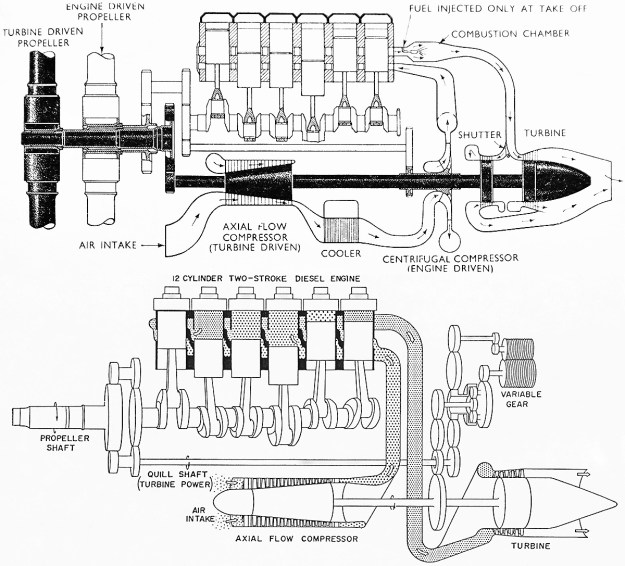

The Spiteful’s Mark numbers were a continuation of those used on the Spitfire. The Spiteful F.XIV (F.14) was powered by a 2,375 hp (1,771 kW) Rolls-Royce Griffon 69 with a five-blade, single-rotation propeller. The Spiteful F.XV (F.15) was powered by the 2,350 hp (1,752 kW) Griffon 89 or 90 with a six-blade, contra-rotating propeller. Both Griffon engines had a two-stage, two-speed supercharger, and both the five- and six-blade propellers were 11 ft (3.35 m) in diameter and built by Rotol. Originally, a Rolls-Royce Merlin engine could be substituted for the Griffon if Griffon engine production was found to be lacking, but the Merlin option was dropped in mid-1944.

The Spiteful had a 35 ft (10.67 m) wingspan, was 32 ft 11 in (9.76 m) long, and was 13 ft 5 in (4.10 m) tall. The aircraft had a maximum speed of 409 mph (658 km/h) at sea level, 437 mph (703 km/h) at 5,500 ft (1,676 m), and 483 mph (777 km/h) at 21,000 ft (6,401 m). Cruising speed for maximum range was 250 mph (402 km/h) at 20,000 ft (6,096 m). The Spiteful’s stalling speed was 95 mph (153 km/h). The aircraft’s range was 564 mi (908 km) on internal fuel and 1,315 mi (2,116 km) with drop tanks. The Spiteful had an empty weight of 7,350 lb (3,334 kg), a normal weight of 9,950 lb (4,513 kg), and a maximum weight of 11,400 lb (5,171 kg). The aircraft had an initial rate of climb of 4,890 fpm (24.8 m/s) and a ceiling of 42,000 ft (12,802 m).

A comparison of the third Spiteful prototype (NN667) and the ninth F.XIV production aircraft (RB523). Both have the elongated intake scoop mounted under the engine and just behind the spinner. Note the larger tail compared to the first two Spiteful prototypes.

With other war work taking priority, it was some time before Supermarine had anything related to the Spiteful to test. A mockup was inspected in March 1944, and the aircraft’s name was changed to Spiteful around this time. A set of wings was fitted to a Spitfire XIV (serial number NN660), which became the first Spiteful prototype. The aircraft was first flown on 30 June 1944, with Jeffrey Quill as the pilot. The aircraft used the same 2,035 hp (1,518 kW) Griffon 61 engine as installed in a standard Spitfire XIV, but its performance was superior to that of a standard Spitfire XIV. However, the Spiteful also exhibited rather violent stalling characteristics compared to the fairly docile stall of the Spitfire. This was attributed to the outer wing with the aileron stalling first, which was the opposite of how the Spitfire’s elliptical wing stalled. With the Spitfire, the outer wing stalled last and enabled the ailerons to remain effective deep into the stall. On 13 September 1944, NN660 crashed while engaged in a dog-fight test with a standard Spitfire XIV. The pilot, Frank Furlong, was killed in the crash. A definitive cause was never determined, but it was believed that the aileron control rods became jammed during moderate G maneuvers.

On 8 January 1945, the second Spiteful prototype (NN664) took to the air, piloted by Quill. The aircraft incorporated updated aileron controls and the new Spiteful fuselage. However, NN664 had a tail similar to that used on the Spitfire F.21. Extensive handling tests were undertaken on NN664 that resulted in a few changes. The most significant change was a redesigned tail with its vertical stabilizer and rudder area increased by 28 percent and its horizontal stabilizer and elevator area increased by 27 percent. NN664 first flew with the new tail on 24 June 1945, and the aircraft was sent to the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE) at RAF Boscombe Down for flight trials.

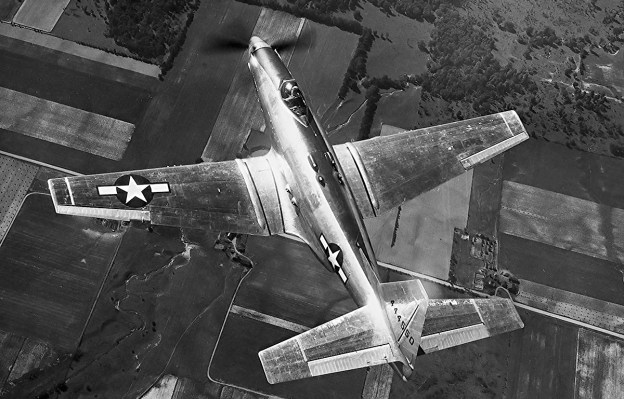

The underside of Spiteful RB515, the first production aircraft, illustrates the wings’ straight leading and trailing edges. Note the standard, short intake scoop. Outlines of the radiator housing doors are visible.

Shortly after NN664’s first flight, the Air Ministry ordered 650 Spiteful aircraft. The order went through a number of reductions, including the cancellation of 150 Spitefuls around 5 May 1945 so that a comparable number of Seafangs (see below) could be ordered. The fourth prototype was included in these cancellations.

The third Spiteful prototype (NN667) was sent to the A&AEE for service evaluations on 1 February 1946. It was found that the aircraft exhibited several areas of poor build quality, and there were numerous concerns with its ease of serviceability. A multitude of fasteners needed to be undone in order to remove the engine cowling, and rearming the aircraft was a time-consuming process that involved disconnecting the controls to the ailerons. A number of modifications and improvements were suggested, but it is not clear just how many were implemented. For at least part of its existence, NN667 had an elongated air intake that would be featured on the Seafang (see below). Other Spitefuls also had the longer scoop (at least RB517, RB518, RB522 and RB523).

The first production Spiteful F.XIV (RB515) made its first flight on 2 April 1945, with Quill in the pilot’s seat. The aircraft originally had an F.21 tail, but a larger Spiteful tail was installed after RB515’s third flight, which ended in a forced landing. The aircraft’s first flight with the new tail was on 21 May 1945. On 27 September 1945, RB515 suffered an engine failure and made another forced landing at Farnborough. The damaged aircraft was subsequently written off.

Another view of RB515 illustrates the larger Spiteful tail that was later applied to the Spitfire F.22 and F.24. The tail improved the Spiteful’s handling, but the aircraft’s stall was still violent compared to the Spitfire’s.

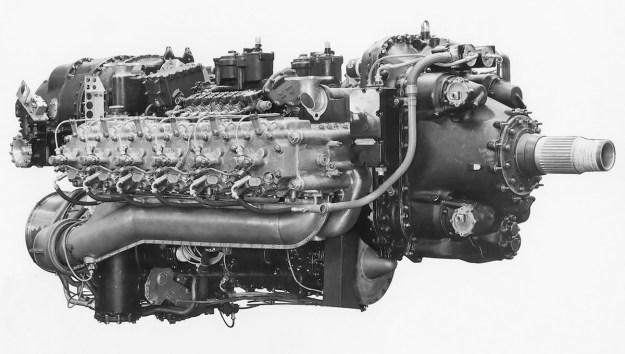

Spiteful RB518 was fitted with a rounded Seafang (see below) windscreen and a 2,420 hp (1,805 kW) Griffon 101 engine to become the sole Spiteful F.XVI (F.16). The Griffon 101 had a two-stage, three-speed supercharger and turned a five-blade, single rotation propeller. In 1947, RB518 achieved 494 mph (795 km/h) at 27,800 ft (8,473 m), the highest level-flight speed recorded by a British piston-powered aircraft. Testing of this aircraft with not-fully-developed engines resulted in seven forced landings—the last was at Chilbolton in March 1949 and resulted in the landing gear being pushed through the wings. The aircraft was then dropped by the recovery crane, ending any hope of repair.

By February 1946, the Spiteful order had been reduced to 80 aircraft. This was again reduced on 22 May 1946 to 22 aircraft, and the Spiteful order finally dropped to 16 aircraft on 16 December 1946. The production order basically covered the aircraft that had been built, although some of the last aircraft may not have flown. A 17th Spiteful, RB520 (the sixth production aircraft), was handed over to the FAA for Seafang (see below) development on 22 September 1945. The aircraft was modified for carrier feasibility trials with a “stinger” arrestor hook incorporated into a special housing below the rudder. RB520 retained the standard, non-folding Spiteful wings.

Powered with a two-stage, three-speed Griffon 101 engine, Spiteful RB518 achieved a level-flight speed of 494 mph (795 km/h), the highest recorded by a British piston-powered aircraft. RB518 was the only F.XVI Spiteful and was subsequently written off after its seventh forced landing.

The production aircraft were serialed RB515 to RB525, RB527 to RB531, and RB535. The final Spiteful was delivered on 17 January 1947. Of the three Spiteful prototypes and 17 production aircraft, most were sold for scrap in July 1948. It appears RB518 was the last Spiteful to fly, and no examples of the type survive. The larger “Spiteful tail” was incorporated into the last Spitfires, the F.22 and F.24.

The Spiteful’s cancellation was based on a number of realities including the more impressive performance of jet aircraft, the end of World War II, and serviceability questions about the Spiteful. While the Spiteful’s speed was impressive, it was below the 504 mph (811 km/h) that was originally estimated. Furthermore, the performance of the aircraft’s laminar wing decreased substantially if there were imperfections, including smashed bugs, on the leading edge. It was unlikely that an in-service warplane would be free of all imperfections.

Spiteful RB520 was loaned out for Seafang development and is considered by some as a Seafang prototype. Note the tail hook housed below the rudder and the “Royal Navy” stenciling on the fuselage.

Back in October 1943, Supermarine designed the Type 382, which was basically a navalized Spiteful. The design had started with mounting a Spiteful-type, laminar flow wing on a Seafire XV. Little official interest was given to the project until 21 April 1945, when the Air Ministry issued Specification N.5/45 for a single-seat fighter for the FAA. Subsequently, Supermarine was awarded a contract for two prototype Type 382 fighters, which became the Seafang. An order for 150 Seafang aircraft was placed on 7 May 1945; this order was essentially a reallocation of Spiteful aircraft that had been cancelled around two days prior.

The production Seafang closely matched the Spiteful but incorporated wings designed so that the last four feet folded vertically. The folding mechanism was hydraulically-powered. The Seafang had an elongated carburetor intake scoop, with the opening just behind the propeller. The aircraft also had a rounded front windscreen rather than the flat plate used on the Spiteful. Under the rudder was a stinger tail hook for catching the arresting cables on the carrier deck. The Seafang’s landing gear was re-enforced to handle carrier operations. The fuel tank behind the cockpit was reduced to 54 gal (45 imp gal / 205 L), resulting in a total internal capacity of 193 gal (161 Imp gal / 732 L).

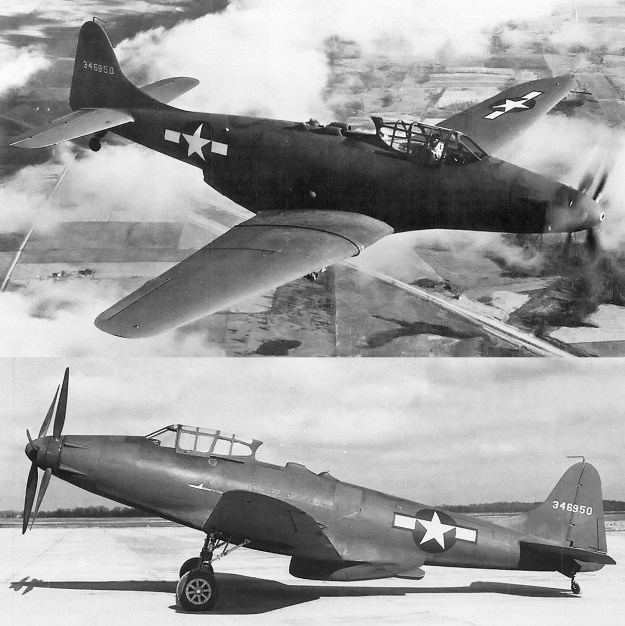

The first production Supermarine Seafang F.31 (VG471) was essentially a Spiteful with arrestor gear. All F.31 aircraft had standard, non-folding wings. Note what appears to be a wide-cord propeller.

Like the Spiteful, two Seafang variants were planned. The F.31 used the 2,375 hp (1,771 kW) Griffon 69 engine with a five-blade, single-rotation propeller, while the F.32 used the 2,350 hp (1,752 kW) Griffon 89 with a six-blade, contra-rotating propeller. The F.31 was basically a Spiteful with an arrestor hook and did not incorporate folding wings. The F.31s would serve as a test aircraft while the F.32 was being developed.

The Supermarine Seafang had a 35 ft (10.67 m) wingspan, was 34 ft 1 in (10.39 m) long, and was 12 ft 7 in (3.84 m) tall. With wings folded, the span was reduced to 27 ft (8.23 m). The aircraft had a maximum speed of 397 mph (639 km/h) at sea level, 428 mph (689 km/h) at 5,500 ft (1,676 m), and 475 mph (764 km/h) at 21,000 ft (6,401 m). Cruising speed for maximum range was 250 mph (402 km/h) at 20,000 ft (6,096 m). The aircraft’s range was 393 mi (632 km) on internal fuel. The Seafang weighed 8,000 lb (3,629 kg) empty, 10,450 lb (4,740 kg) with a normal load, and 11,900 lb (53,98 kg) maximum. The aircraft had an initial rate of climb of 4,630 fpm (23.5 m/s) and a ceiling of 42,000 ft (12,802 m).

The side view of Seafang VG471 illustrates many of the aircraft’s features: long intake scoop, straight wing edges, radiator scoop doors, rounded windscreen, bubble canopy, large tail, and arrestor hook.

As previously mentioned, some Spitefuls had the long intake carburetor scoop; RB518 had a Seafang windscreen; and RB520 was fitted with an arrestor hook (resulting in some sources classifying it as a Seafang prototype). This was all done to lead up to Seafang F.31 production aircraft, which were basically Spitefuls with arrestor hooks. The first Seafang F.31 was VG471, which followed the fifth Spiteful off the production line. All of the F.31s had the five-blade propeller, lacked folding wings, and would end up the only production Seafangs that were completed. VG471 was first flown in early January 1946 and used in arrestor hook trials. The original hook installation proved to be weak, and a redesigned system was installed in March 1946. The aircraft passed the trials on 1 May.

The prototype Seafang F.32s were serial numbers VB893 and VB895, and both had contra-rotating propellers and folding wings. VB895 was first flown in early 1946 and was delivered to the A&AEE on 30 June. In August 1946, VB895 was demonstrated separately to the Royal Netherlands Navy, French representatives, and United States representatives in an attempt to sell the Seafang to allies. However, no orders were placed. In May 1947, test pilot Mike Lithgow successfully performed deck trials in VB895 on the HMS Illustrious. The aircraft’s wide track landing gear drastically increased its stability while on the ground, and the contra-rotating propeller eliminated the torque effect. VB895 was also tested with a single, fuselage-mounted 204 gal (170 Imp gal / 773 L) drop tank, and the aircraft was used for armament trials. During a static test firing of the cannons on 18 May 1948, a build-up of gases in the left wing resulted in an explosion that damaged the wing. Extra vents were added, and no further issues occurred.

The Seafang F.32 prototype VB895 was the first fully-navalized aircraft of the series. The contra-rotating propellers eliminated the torque effect that led to the downfall of many aviators, especially when operating from the short deck of an aircraft carrier.

While praised for its handling and responsiveness, the Seafang did not offer any real advantage over the Seafire 47, and the Seafang’s stall was certainly a disadvantage. An order was subsequently placed for the Seafire. The original interest in the Seafang was based on doubts regarding the suitability of jet aircraft for carrier operations. As those doubts faded, so did interest in the Seafang, and the aircraft was cancelled. A few Seafangs were kept active for a brief time to continue evaluating the laminar flow wing, which was used on the Supermarine Type 392 Attacker. The Attacker was often referred to as a “Jet Spiteful,” although it had Seafang folding wings with the radiators removed and additional fuel tanks installed. The Attacker first flew on 27 July 1946, and it was the first jet fighter to enter operational service with the FAA.

Eighteen production Seafangs were built, carrying serial numbers VG471 to VG490. The first 10 aircraft were F.31s, and the remaining eight were F.32s. However, only the first eight or so aircraft were completed, with the remaining units delivered disassembled. Sadly, like the Spiteful, all of the Seafang examples were scrapped.

Note: The Royal Air Force and Fleet Air Arm used Roman numerals for mark numbers up thorough 1942. From 1943 through 1948, the Roman numerals were phased out for new aircraft, and Arabic numerals were applied. From 1948 onward, Arabic numerals were used exclusively. The Spitefuls were typically referred to using Roman numerals, but the slightly later Seafang used Arabic numerals. The use of both Roman and Arabic numerals in this article refers to the most common use applied for the particular aircraft type.

The folding wings on Seafang VB895 were hydraulically operated and decreased the aircraft’s wingspan by 8 ft (2.4 m). Although, the wide tack landing gear contributed to snaking at low speeds, it enhanced the stability at higher speeds and as the aircraft slammed down on a carrier deck.

Sources:

– Spitfire: The History by Eric B. Morgan and Edward Shacklady (2000)

– British Experimental Combat Aircraft of World War II by Tony Buttler (2012)

– Supermarine Aircraft since 1914 by C.F. Andrews and E.B. Morgan (1981)

– Ultimate Spitfires by Peter Caygill (2006)

– Supermarine Fighter Aircraft by Victor F. Bingham (2004)

– Griffon-Powered Spitfires by Kev Darling (2001)

– Fighters: Volume Two by William Green (1961)

– Interceptor Fighters for the Royal Air Force 1935–45 by Michael J.F. Bowyer (1984)

– Spitfire: A Complete Fighting History by Alfred Price (1992)

– Wings of the Weird & Wonderful by Captain Eric Brown (2012)