By William Pearce

Ab (David Abbot) Jenkins was a devout Mormon who did not drink or smoke. He made a name for himself by setting numerous long distance and endurance automotive records. He was one of the first people, perhaps the first, to run on the Bonneville Salt Flats when he took his motorcycle there in 1910. In the 1920s, he set many promotional records for Studebaker, even beating a train from New York to San Francisco in 1926. In the early 1930s, he acted on his belief that the Bonneville Salt Flats would be an ideal venue for automotive speed records.

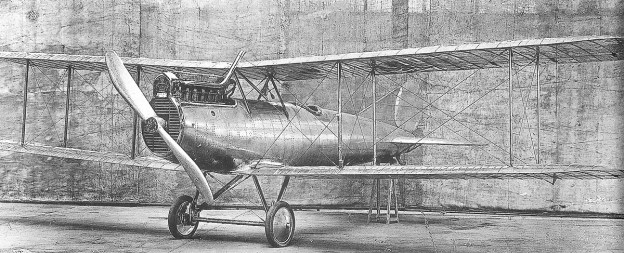

The newly completed Duesenberg Special in June 1935. From left to right: Augie Duesenberg, Ab Jenkins, Harvey Firestone, and John Thomas.

In the early-1930s, Jenkins organized a number of speed runs at Bonneville and set many records, including a flying 1 mi run at 65.45 mph (105.33 km/h) on an Allis-Chalmers tractor and a 24 hour run in a modified Pierce-Arrow at 127.229 mph (204.755 km/h), covering 3,053 mi (4,913 km). The endurance runs were on a 10 mi (16 km) circular course. These events made the Bonneville Salt Flats the premier destination for international contestants looking to set speed and endurance records.

In 1934, Jenkins was looking to better his 24 hour record. With the support of Errett L. Cord, whose company controlled Duesenberg Inc, a special Duesenberg car was built for Jenkins to set endurance records at Bonneville. Augie Duesenberg was involved with the design of this car. The endurance racer was originally known as the Duesenberg Special.

The Duesenberg Special was built on a standard 142.5 in (3.62 m) Duesenberg J chassis and was intended to be driven on the street with minimal changes. For higher speeds, the gear ratio of the rear axle was dropped to 3.0 to 1. The car used a standard Duesenberg eight-cylinder, inline engine with a 3.75 in (95 mm) bore, 4.75 in (121 mm) stroke, and displacing 420 cu in (6.9 L). The engine was supercharged and had dual overhead camshafts. The standard engine produced 320 hp (239 kW); however, the Duesenberg Special’s engine had special grind camshafts, larger carburetors, a larger impeller for the supercharger, and updated intake manifolds that increased the engine’s output to 400 hp (298 kW) at 5,000 rpm. An identical spare engine was also built for the Duesenberg Special.

The body of the Duesenberg Special was designed by Herbert Newport and was streamlined to minimize the car’s frontal area. Newport’s design included a single headlight positioned below the sloped radiator. The two seats were staggered slightly to keep the car’s body narrow. The front suspension was lowered, and large Firestone tires were fitted onto 18 in (.46 m) wire wheels. Behind each wheel was a fairing designed to reduce air turbulence. Detachable fenders were used for normal road travel. The Duesenberg Special was 18.5 ft (5.64 m) long, had a 56.1 in (1.42 m) track, and weighed 4,800 lb (2,177 kg).

The Duesenberg Special makes a pit stop after a grueling run on the salt flats. Note the straight-pipe exhaust extending from the eight-cylinder Duesenberg engine to the back of the car.

Once completed, the Duesenberg Special was tested on the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and then shipped to Salt Lake City, Utah. Meanwhile, on the Bonneville Salt Flats in July 1935, Briton John Cobb had bested Jenkins’ 24 hour record in his aero-engined Napier-Railton racer. Cobb set the new mark in the 450 hp (336 kW) Napier Lion-powered machine at 134.850 mph (217.020 km/h)—over 7.5 mph (12 km/h) faster than Jenkins.

Jenkins and the Duesenberg Special were soon on the Bonneville Salt Flats. Jenkins quickly took the one hour record at 143.42 mph (230.81 km/h), but shortly after, an engine bearing burned out. A couple of weeks later, both engines were back from Indianapolis with new bearings, and Jenkins was back on the salt flats. Jenkins and his relief driver Tony Gulotta had run the Duesenberg Special for 1,960 mi (3,154 km) and averaged over 138 mph (222 km/h) when the engine failed. The spare engine was installed, and over 29 and 30 August 1935, Jenkins retook the 24-hour record by covering 3,354 mi (5,398 km) at an average of 135.580 mph (218.195 km/h)—less than one mph (1.6 km/h) faster than Cobb.

Ab Jenkins in the Conqueror-powered Mormon Meteor II. Note the rudimentary fin to increase the car’s directional stability at high speeds; it was one of many tried.

The new record was short lived. In September 1935, Capitan George Eyston, another Briton, upped the 24 hour record to 140.52 mph (226.15 km/h). Eyston used a 500 hp (373 kW) Rolls-Royce Kestrel V-12 aircraft engine in his streamlined Speed of the Wind racer to best Jenkins’ record by 5 mph (8 km/h).

Per an existing agreement, Jenkins purchased the Duesenberg Special for $4,500 (and $300 in expenses). A name change was in order, and the Salt Lake City Desert News held a contest to rename the car. The winning name was the Mormon Meteor. Jenkins knew that he would need more power to win back the record.

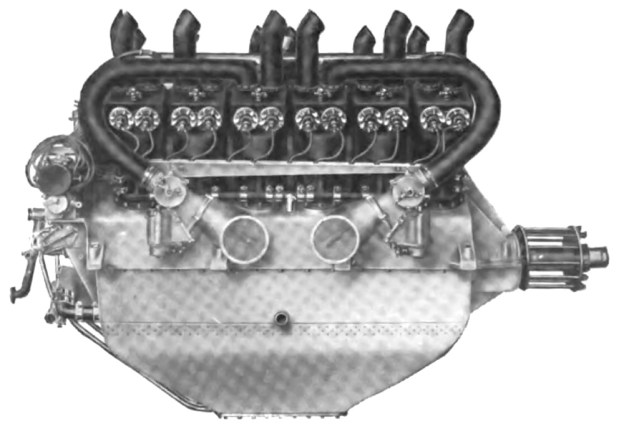

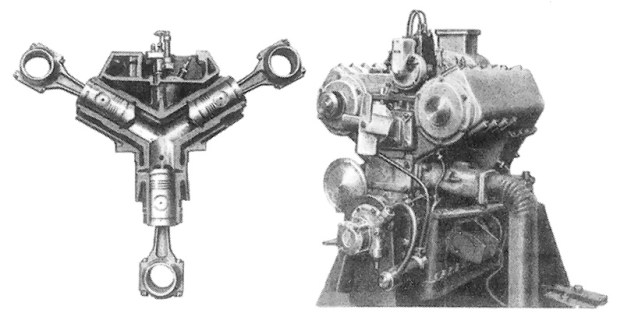

Like Cobb and Eyston, many land speed racers had switched to aircraft engines, and Jenkins saw the 400 hp (298 kW) eight-cylinder engine as the Duesenberg Special‘s weak point. Jenkins acquired two 1,570 cu in (25.7 L), 750 hp (559 kW), V-12 Curtiss Conqueror aircraft engines. One would be used in the Mormon Meteor and the other held as a spare.

The Mormon Meteor II in its final Curtiss Conqueror-powered form. Note the improved fin and additional lights.

Augie Duesenberg drew up the plans to shoehorn the Conqueror engine into the Mormon Meteor. A new bell housing, flywheel, clutch, and other parts for the conversion were made by the Lycoming Machine Company. Augie, aided by Marvin Jenkins, Ab Jenkins’ young son, oversaw the installation of a Conqueror engine in the Mormon Meteor at the Auburn auto plant in Auburn, Indiana in early 1936. Other modification included a tail fin to increase the vehicle’s directional stability at high speeds. The decision was made to rename the car Mormon Meteor II as a result of all the changes.

By this time, Eyston had returned to Bonneville and set new records. In the Speed of the Wind, Eyston upped the 24 hour record to 149.096 mph (239.947 km/h) and set a 48 hour record at 136.349 mph (219.432 km/h). Jenkins in the Mormon Meteor II beat Eyston’s 12 hour speed, averaging 152.84 mph (245.97 km/h), but was forced to quit shortly after with a failed drive shaft. While the Mormon Meteor II was down for repairs, Cobb took to the salt and beat Eyston’s 24 hour speed—averaging 150.163 mph (241.664 km/h).

Jenkins, with Babe Stapp as his relief driver, broke yet another set of records on 22 and 23 September 1936. The Mormon Meteor II averaged 153.823 mph (247.554 km/h) for 24 hours and 148.641 mph (239.215 km/h) for 48 hours—covering 3,692 mi (5,942 km) and 7,135 mi (11,483 km), respectively. On 21 and 22 September 1937, Jenkins, and relief driver Lou Meyer, increased the 24 hour record to 157.270 mph (253.102 km/h), covering 3,774 mi (6,074 km) in the Mormon Meteor II.

As good as the Mormon Meteor II was, the Duesenberg chassis was not built for the heavy 750 hp (559 kW) engine. In 1937, Jenkins commissioned Augie Duesenberg to design a new car able to accommodate the Curtiss Conqueror. The new endurance racer was known as the Mormon Meteor III. The Mormon Meteor II had its Conqueror engine removed; the Duesenberg straight eight was reinstalled, and the car was made usable for normal road travel. Jenkins had the car painted burgundy and rechristened it the Mormon Meteor.

Ab and Marvin Jenkins used the Mormon Meteor for personal transportation as well as in parades in Salt Lake City, of which Ab Jenkins had been elected mayor. After putting another 20,000 mi (32,000 km) on the Mormon Meteor, Jenkins sold the car in 1943. The Mormon Meteor passed through a few owners until it was purchased at auction in 2004 by Harry Yeaggy for $4.45 million. Yeaggy had the car carefully restored to its original 1935 condition, earning it Best of Show at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance in August 2007. That honor was followed by Best of Show wins at the Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance in March 2011, the Elegance at Hershey in June 2014, and the Arizona Concours d’Elegance in January 2016. The Duesenberg Special / Mormon Meteor is considered one of the most important Duesenberg automobiles in existence.

The beautifully restored Duesenberg SJ Mormon Meteor Special (returned to its 1935 configuration) at Pebble Beach, CA. (Wouter Melissen image via ultimatecarpage.com)

Sources:

– Ab & Marvin Jenkins by Gordon Eliot White (2006)

– “They Always Called Him Augie” by George Moore, Automobile Quarterly, Vol. 30, No. 4 (1992)

– http://www.hemmings.com/hcc/stories/2007/12/01/hmn_feature1.html

– http://www.supercars.net/cars/2480.html

– http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Speed_of_the_Wind

– http://www.sportscardigest.com/amelia-island-concours-delegance-2011-best-of-show-winners/

– http://www.sportscardigest.com/elegance-hershey-2014-report-photos/

– http://blog.hemmings.com/index.php/2016/01/27/mormon-meteor-duesenberg-takes-best-of-show-at-arizona-concours-delegance/?refer=news