By William Pearce

In the late 1920s, Desire Joseph Deschamps moved forward with his vision of an inverted, two-stroke, high-speed, diesel aircraft engine. Deschamps had immigrated to the United States from Belgium, where he had worked for the Minerva Company. Reportedly, Deschamps had a hand in designing Minerva’s first aircraft engine, which was also the first aircraft engine to incorporate Knight sleeve-valves (two sleeves).

Deschamps rotary valve as outlined in U.S. patent 2,064,196. On the left is a transverse sectional view of the cylinder with the rotary valve below (inverted engine) and feeding to the combustion chamber. On the right is a side view of the rotary valve for two cylinders revealing the various ports in the valve.

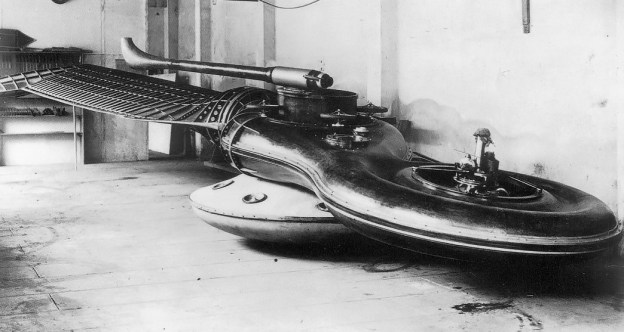

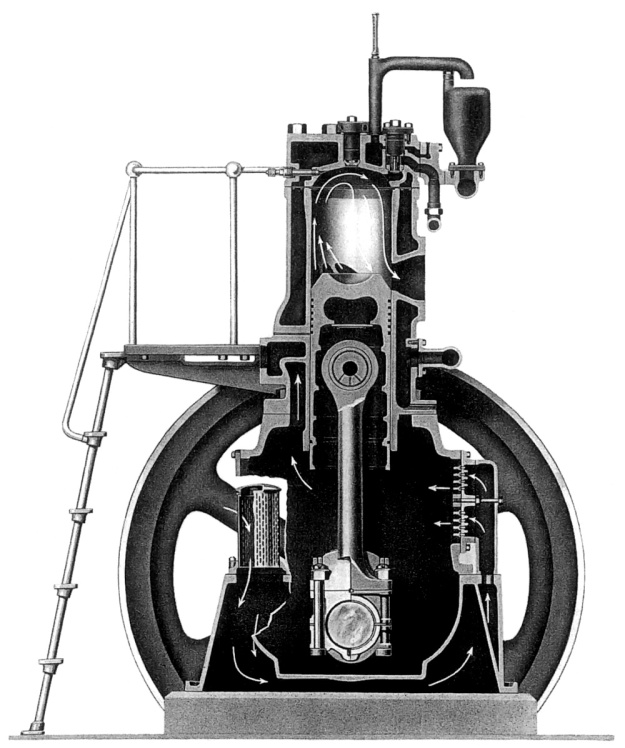

Working out of St. Louis, Missouri, Deschamps began the design of an inverted, liquid-cooled, straight six-cylinder, diesel aircraft engine. Outlined in U.S. patent 2,064,196, what was unique about this diesel engine was the use of a rotary sleeve valve. This rotary valve was essentially a cylindrical tube that ran the length of the engine below (inverted engine) the combustion chamber. Induction air flowed through the tube that rotated at half crankshaft speed. As the tube rotated, ports in the tube aligned with a port to the cylinder, allowing fresh air to force the exhaust gases out of the cylinder and provide air for the next combustion cycle. The exhaust ports were around the cylinder wall and covered/uncovered by the piston.

From all accounts, the rotary valve engine was never built. A more conventional valve arrangement was adopted, utilizing poppet-valves, rather than the rotary valve, for the intake . A two-cylinder test engine was built and run in the early 1930s. The test engine engine developed 174 hp (130 kW) at 1,600 rpm. This two-cylinder engine was expressly for the development of the Deschamps inverted V-12 diesel, having the same bore, stroke, and general configuration of the larger engine to come.

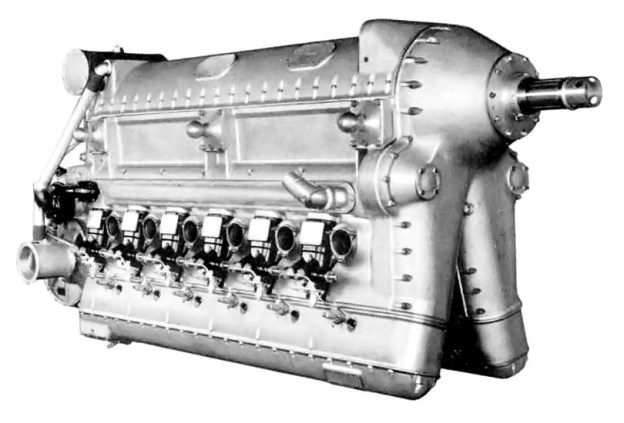

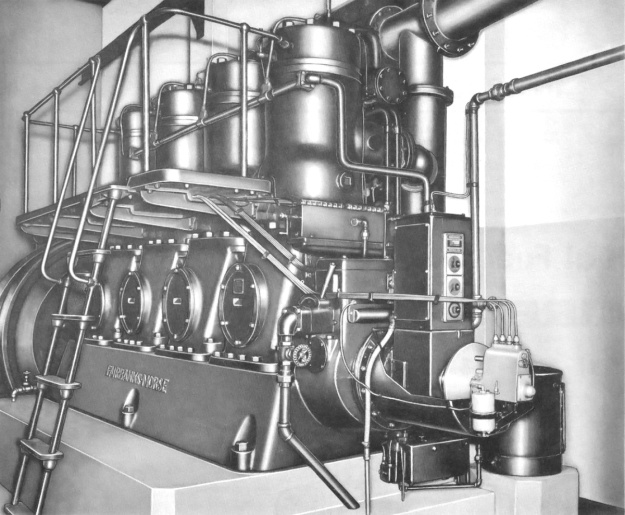

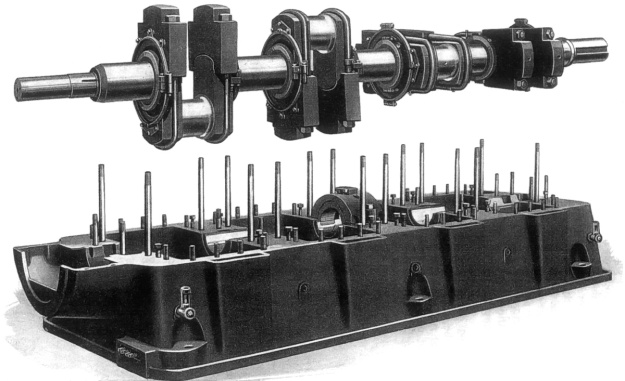

The Deschamps V 3050 was an inverted, 12-cylinder, diesel aircraft engine of all aluminum construction. The engine was built by the Lambert Engine and Machine Company in Moline, Illinois and completed in 1934. The cylinder banks were arranged in a 30-degree Vee to minimize the engine’s frontal area. With a 6.0 in (152 mm) bore and 9.0 in (229 mm) stroke, the engine had a total displacement of 3,053 cu in (50.0 L). The liquid-cooled, direct drive engine produced 1,200 hp (895 kW) at 1,600 rpm for takeoff and 950 hp (708 kW) at 1,500 rpm for cruise. Fuel consumption was 0.41 lb/hp/hr (249 g/kW/h). When built, it was one of the largest and most powerful diesel aircraft engines in the world.

The compression ratio of the V 3050 was 16 to 1, and air was forced into the cylinders by two gear-driven GE superchargers. The centrifugal superchargers were driven at 13.5 times crankshaft speed (21,600 rpm) and provided air at 12 psi (0.83 bar). Cylinder scavenging for the two-stroke cycle required eight psi, leaving four psi for boost. A small portion of the air entering the superchargers was taken from the crankcase to provide ample ventilation and burn away any fuel vapors. Sea-level power could be maintained to an altitude of 10,000 ft (3,048 m).

Each bank of cylinders had an intake manifold on the inside of the Vee to deliver air from the superchargers to the cylinders. The compressed air entered each cylinder via two poppet valves actuated simultaneously by an overhead camshaft driven at crankshaft speed.

Rear view for the Deschamps diesel highlighting the two GE superchargers. The glow plugs are also visible on the right cylinder bank.

A ring of 12 exhaust ports was located in the cylinder wall and exposed by the piston. To prevent excessive oil consumption and exhaust smoke, a small horizontal groove was cut in the cylinder wall just below each of the 12 exhaust ports. The grooves in the cylinder liner aligned with an annular groove in the cylinder casing wall. The annular grooves for all 12 cylinders were connected to a vacuum pump that scavenged oil from the pistons. The amount of oil stripped from the pistons was controlled by the amount of vacuum.

The superchargers and camshafts were driven from the crankshaft via separate vertical shafts with bevel gears. A Lanchester type torsional vibration damper was incorporated on the rear of the crankshaft to protect the gear drives. The damper was combined with a torque limiter clutch that would slip momentarily under sudden changes in torque.

Each bank of cylinders had independent intake delivery, exhaust, liquid-cooling connections, oil connections, oil and fuel pumps, and fuel injectors. In theory, each bank could be operated independently of the other bank, sharing only a common crankshaft. At 1,600 rpm, oil was circulated at 80–100 psi (5.5–6.9 bar) while coolant circulation was at 230 gpm (871 l/m).

Fuel was injected directly into each cylinder via two Deschamps-designed (U.S. patent 2,020,302) fuel injectors operating at 3,500 psi (241.3 bar). The two injectors per cylinder alternated supplying fuel into the cylinder, each firing every-other compression stroke. For slow rpm operation, one injector was shut off, essentially making the engine a four-stroke. This kept the engine running smoothly and the cylinders warm for instant application of more power. One fuel pump for each engine bank was used and supplied fuel at 15 psi (1.0 bar) with a maximum flow of 150 gph (9.4 l/m).

The engine was air-started by a compressor charged to 850 psi (58.6 bar). For staring the engine in cold weather, glow plugs were provided in the right cylinder bank while the left bank’s intake valves were kept open with the fuel shut off. A reversing gear could be fitted for utilizing the engine in airships. The V 3050 was 26.5 in (0.67 m) wide, 49.5 in (1.26 m) tall, and 99 in (2.52 m) long. It weighed 2,400 lb (1,089 kg) with all accessories, giving it 2.0 lb/hp (1.2 kg/kW).

After completing the engine, no funds remained for testing. Deschamps met with the Army Air Corps Power Plant Laboratory in June 1934, but it seems no further testing was done on the engine. Deschamps went on to work for various aviation corporations, patenting a number of fuel injectors and pumps along the way. Amazingly, the Deschamps V 3050 diesel engine survives and is in storage at the National Air and Space Museum’s Garber Facility in Silver Hill, Maryland.

Deschamps Diesel in storage at the National Air and Space Museum’s Garber Facility in Silver Hill, Maryland. (Fred van der Horst image via the Aircraft Engine Historical Society)

Sources:

– Aircraft Diesels by Paul H. Wilkinson (1940)

– Aerosphere 1939 by Glenn Angle (1940)

– Diesel Aviation Engines by Paul H. Wilkinson (1942)

– Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft 1934 by C. G. Grey (1934)

– “A 1,200 H.P. Diesel Engine.” Flight. May 24, 1934

– “Internal Combustion Engine” U.S. Patent 2,064,196 by Desire J. Deschamps (1930) pdf